The 2016 Rabbit Island Artist in Residence Exhibition opening reception is tomorrow evening, September 27th, at 6:30pm at the DeVos Art Museum on the campus of Northern Michigan University in Marquette, Michigan. Please join us! The exhibition runs until November 12th.

In addition to the exhibition, the exhibiting artists have arrived over the past several days and will be presenting their work and island experiences through a series of events the museum is hosting.

Monday, September 25 – 3pm

Artist Talk by Walter van Broekhuizen

Wednesday, September 27 – 6pm

Film screening and talk with Jack Forinash, Kelly Gregory, and Mary Rothlisberger

Wednesday, September 27 – 6:30pm

Reception: Rabbit Island Artist in Residence Exhibition

Thursday, September 28 – 3pm

Performative Lecture with Luce Choules

Congratulations 2017 Residents

We are pleased to announce the awarded residencies for the 2017 program on Rabbit Island. Last fall we received 223 applications representing individuals and artist groups from 26 countries. The selection committee—comprised of cofounders Rob Gorski and Andrew Ranville, DeVos Art Museum director Melissa Matuscak Alan, and former Rabbit Island residents Beau Carey, Nich McElroy, and Josefina Muñoz—spent seven weeks reviewing applications and deliberating internally, finally awarding residencies to the six artists featured below.

The process for this years program was especially challenging due to the quality and thoughtfulness of applications. This is how we worked: After researching each proposal in detail and hosting several long discussions, the committee created a list of 10 finalists. Each of the finalists were then interviewed in a 20 minute videoconference during which committee members and applicants asked questions of each other. The six-person committee then continued discussing the quality of each artist’s previous work, conceptual strength of their proposal, its relationship to both the Rabbit Island program and wider contemporary issues, and the artist’s ability to demonstrate competence in the wilderness environment. It is safe to say all 10 finalists interviewed were deserving of a residency, but due to limitations related to our annual funding, maintaining the ecological integrity of the island environment, and the brief summer period on Lake Superior, the committee made the challenging decision to award four residencies. This conclusion was reached after a thoroughly democratic numerical voting process.

Interestingly, and also unintentionally, the six awarded residents make up three collaborative twosomes. It will be interesting to see how small group dynamics—in each case strongly established through previous shared projects—are manifested within the wilderness environment of Rabbit Island.

The committee sincerely thanks each applicant who offered exceptional work and a carefully considered proposal. We are excited to be working with the following artists over the next year. This year we choose to share the awarded proposals in full—providing the community a peek at the critically rigorous, thoughtful, and adventurous proposals we receive. While the time leading up to their residency and experience on the island may transform the original concepts and methods of our awarded residents, the 700+ applications we have received over the last four residency calls offer a facinating glimpse at the state of today’s discourse on the intersection of art and ecology.

Julieta Aguinaco and Sarah Demoen. After meeting at the Dutch Art Institute in 2013, Aguinaco (Mexico City, Mexico) and Demoen (Brussels, Belgium) have worked collaboratively since. By combining their respective interests in performance and writing, their works often question and challenge notions of institutionalized art and politics. Together they have recently presented work in Mexico City, Mexico; Berlin, Germany; and Arnhem, The Netherlands.

Their statement and proposal:

Julieta Aguinaco and Sarah Demoen met in 2013 at the Dutch Art Institute, and have been working collaboratively since. In her individual practice, Julieta focuses on non-linearity, questioning where to place things that do not match the hierarchical, categorical system that dominates our ways of knowing. She researches the geological history of the earth and the land we walk on and tries to destabilize the notion of private property in light of non-western cosmovisions. Sarah has an interest in the history of resistance and alternative ways of institutionalizing. In this, she tries to critically disrupt preconceived notions about art, politics (social movements) and ownership, primarily through language.

In their joint practice, Julieta and Sarah combine their respective research interests into a dynamic discourse resulting in writing and performance. In a constant to and fro, they discuss their issues of concern directing critical questions at each other and the world, driven by a strong focus on process. They take on roles: where Julieta is the artist, Sarah is the anti-artist; where Julieta looks for visibility, Sarah is looking for abandoned places outside of the attention economy. Together, they create a philosophical form of theater, where poetics and fiction could be a way to withdraw from the linear world. They are convinced that alternatives can be found in the paradoxes, in non-linearity; in that what’s easily ignored.

An important question running through their work is: what can be named and known without undoing or destroying that same thing? In previous works they discussed the desert landscape and the influence of human colonization; the question: ‘you don’t find a different paradigm, we make it!’ and the idea of utopia as immanent in the here and now, and not as some far-fetched idea in the future.

When You Cut into the Present, the Future Leaks Out (working title)

’It is not yours,’ the one-eyed woman said with the mildness of utter certainty. ‘Nothing is yours. It is to use. It is to share. If you will not share it you cannot use it.’ (The Dispossessed, Ursula Le Guin)

The fresh water cephalopod could be an animal that lives in the depths of Lake Superior. It would have eight inky legs, a giant head, a glimmering opacity and the skills to survive in waters with a very low oxygen level. Its shape could be amorphous; radiating with pink, blue and yellow colors as the cephalopod takes on the role as the overarching umbrella for a small but vibrant community of corpuscles that constitute the shapeless blob. Creatures crawling, swimming and climbing through and over and into one another, sharing space and place without appropriating it. There is no pecking-order here, no room for dichotomies, no hierarchy. This lot can become anything and commit to everything. (i) At present, this taxon of cephalopods does not exist. Nor in the Great Lakes, nor in any other fresh water pool in the world. However, millions of years ago, the area where Rabbit Island is located used to be a shallow sea, with salt water. (ii) Who can claim then that there was never an octopus seen on the shores of Lake Superior?

What once was, could become again, and even grow beyond itself. Speculation and fictionalization offer a key for past, present and future to come together in a non-linear way; where diverse, collective forms of living and paradoxes are embraced. The way the not-yet-existent fresh water cephalopod would live, with and through multiple other organisms, constructs an image of what a possible future world could be. But to summon the fictive fresh water cephalopod into a future life form, a method is needed. We believe Rabbit Island is the place for developing that method as it has hardly been touched or modified by human hands.

American poet William S. Burroughs’ famous quote: ‘When you cut into the present, the future leaks out’, could bring that future cephalopod to life. The sentence refers to the cut-up technique in poetry and literature, where parts of text are literally cut out, mixed up and ordered into new texts. This aleatory method of collecting and rearranging pieces of the present through a creative process, allows for chance to enter the work, not in an undetermined way, but as a factor that doesn’t ignore the paradoxes inherent to existence. Paradoxes are often discarded as redundant, for in their complexity, they do not offer straightforward and easy answers. We believe that exactly in those paradoxes there might be some possibilities for a future ‘to leak out’. We do aim for a different future than the one at present: a future devoid of the consequences of global warming, devoid of the destructive forces of the neoliberal economy where 1% of the world population has access to all wealth, and devoid of an oversimplified vision of complex dimensions.

To collect the material for the cut up method, we will set up The RI-School - a place for epistemic disobedience. (iii) The RI-school will make it possible to take a class with plant and fish, soil and rock. It will organize courses, lectures and field trips on the island for H2O, nonvascular plants, vertebrates and anthropoids. We are aware that this way of gathering knowledge through a school is an anthropocentric, western manner, that will lead to bringing human-inspired subjective findings to the mainland. Also, many ‘alternative’ forms of knowledge are already inherent to this area as indigenous people have been roaming these waters for centuries. How can we – through this known educational format – learn from the island’s clarifying content? If we want to understand and translate an alternative knowledge, we need to epistemologically disobey; to deliberately undermine the western structures we have been brought up with. A rebelliousness towards that system of dual categorization, of hierarchy and ownership, we know and live in. Could this island give us a different understanding of the larger contingencies happening on the mainland?

Practically, the classes, seminars and field trips are documented through sound recording and our written notes. We will be recording some typical sounds of nature: wind in a tree, the flapping of a bird’s wings, hands digging a hole, the insect’s buzz, etc. Not to romanticize nature - with a beautiful sunset always comes a group of bloodsucking mosquitoes - but to give it a voice in the conversation. Also, we will record the noise we make during class, the sound of written words read out loud to the land, to the water, to each other. There will be discussions about forms of resistance in nature and culture alike, renewal through fictionalization, the potency of mimicry and theories of exit. The selected texts will handle the story of the non-existent fresh water cephalopod, they will question us setting up a school on an island without an invitation from that island, and whether to get to know each other is also to eventually destroy each other? Next to our own essays and scribbles and the island’s contributions, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness by Donna Haraway will function as a basic textbook, as she talks of the impossibility to split between nature and culture. The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin will be another study-book as it deals with the discrepancy between two planets, one capitalist, earth-like, the other anarchist, arranged as a place of equality and solidarity. This overload of different materials is necessary to make the collection of present material for an aleatory purpose, constructing a constellation from which a possible future might leak out.

Since the island remained untouched by human colonization of land and resources, it symbolizes a pre-capitalist world and is therefore indispensable for research into different ways of living. As an epitome of larger society, its land, water and species have the capacity to re-map past, present and future. We think our collection of sound pieces and text, where nature and culture are protagonists alike, through the cut up technique, could bring that potential into the larger world, where there is a pressing need for a leak of another future than the one we are heading towards. We want that utopian cephalopod to become alive, not as some far-fetched forthcoming ideal, but here and now, starting at Lake Superior.

The final outcome is a soundscape which we will present in the small forest outside of the museum. The soundscape contains the information gathered through the RI-school, cut up and edited into complex layers of sound fragments containing text, different voices, recordings from the seminars and natural sounds form the island. This sound piece will enter into a conversation with the noises and voices that surround the museum. In addition, we will do a small performance as we will take a class with the local ‘fouled’ nature. Inside the museum, a publication with our notes and texts and drawings from the time on the island will form another element of the work. This ‘textbook’ is freely available, for as mentioned in the above quote: ‘nothing is ever yours, it is to use, to share’. What else is the point of working towards a future ideal if it is not shared, used and altered; no one owns the future.

Rachel Pimm and Jasmine Johnson. London-based Pimm and Johnson met during their MFA studies at Goldsmiths University. Collaboratively they assist each other in the realization of their individual works, and collectively as part of the group MoreUtopia!, of which they are members. Both work across disciplines utilizing video, writing, performance, drawing, and sculpture to investigate complex systems both artificial and natural. Recent program participations and exhibitions include the Serpentine Gallery, Chisenhale Gallery, Jerwood Visual Arts, and Bloomberg New Contemporaries.

Their statement and proposal:

Johnson & Pimm are partners who both live and work in London, where they met during an MFA in Fine Art from Goldsmiths College, London. Since 2011 they have collaborated unofficially on each others’ individual projects and officially as two members of MoreUtopia! including a recent solo exhibition at ANDOR, London (2016).

Rachel Pimm works in sculpture, video, writing and performance to make work that explores ecosystems and their materiality, both natural and artificial, often from the point of view of non-human agents, such as plants, worms, water, gravity or rubber. American architect and urbanist Keller Easterling described her recent work Polymethyl Methacrylake as a ‘plastic fossils as the new confetti of empire or geological traces suspended in a matrix of global currents’.

Jasmine Johnson works in video, sculpture and drawing. Recent work explores modes of escape and wildness as a progressive prospect, playing to the propensity of individuals and societies to consult the ‘then’ and ‘there’ for clues for how to negotiate the ‘here’ and ‘now’. An ongoing series of video works stem from encounters that Johnson has had with individuals in different locations (UK, Russia, Lithuania and India) who then become central characters in the work.

Interrelations between an ancient tablet with prophetic instructions and a formula for painting with electricity form the basis of SURFACE NORMALS, a CGI video work and series of copper conductive paintings, which explore recorded manifestations of human presence and time passing on in its widest sense.

SURFACE:

The outside face, the uppermost or most superficial layer, the cosmetic skin of something. To surface is to uncover, or to come to the top.

NORMALS:

Usual, typical, expected state, or a term in geometry which refers to the rising and falling of a level on a plane. In CGI modelling, this is a word describing the approximate value used to calculate the image of surfaces.

In every specific location there is a conflation of histories, economies, mythologies, politics, matter and movement. For Rabbit Island, itself a volcanic remnant of a tectonic shift, these consist as a web of intricately connected links to water, trade routes, national boundaries and the extraction of resources. Mining on the copper rich ridge of the neighbouring Keweenaw Peninsula played a pivotal role in human history and technology, the successful extraction of which played a large part in making Europe rich.

Operating under the Rabbit Island’s policy of ‘leave no trace’, we will respond to the movements and extractions following a local myth that originates from archaeological fragments dated to the Bronze Age rumoured to have been lost along with an unknown quantity of missing copper in the waters of Lake Superior. Among which, the Newberry Tablet (circa 3000 BC, discovered in 1890, Michigan) is said to prove Pre-Columbian contact with Europe and now resides in the Michigan Historical Museum in Lansing.

In 1890, James Scotford, a sign painter from Edmore, MI, claimed he had found a number of artifacts, including clay cups and carved tablets, with symbols on their surfaces resembling hieroglyphics. Nearly 3000 relics appeared to suggest that ancient Near Eastern civilisations had lived in the state of Michigan, evidencing Pre-Columbian contact with Europe. Using trade routes galvanized for mining, Scotford sold and transported the 3000 artifacts out from the area including the Newberry Tablet. One archaeologist translated the symbols on the tablet as an ancient Hittite-Minoan formula for getting good luck from the gods. According to another translation, the symbols were describing a bird eating grain. Most of the relics were widely discredited due to symbols not matching with the Minoan symbols of the period, marks being clearly made by more modern tools, or hieroglyphics with characters that were upside-down. In 1911, Scotford’s stepdaughter signed an affidavit stating that she had actually seen him making the objects. The Newberry Tablet was lost for many years and when it resurfaced, it had evaded such discrediting. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints kept 797 of the objects including the tablet in the Salt Lake City Museum and gave them up to the Michigan Historical Museum in Lansing where they currently reside.

SURFACE NORMALS poses the possible translations of the Newberry Tablet as two viewpoints on this legacy of copper and water, and the ways in which human activity and natural resources are increasingly hybridised: 1. It’s a formula for good luck, 2. It’s about a bird eating grain (or 3. it’s not translatable). We propose to create work that does not leave a trace in the physical makeup of Rabbit Island, but maps onto it a digital path mimicking the flow of water, or the hyperspeed of the conductivity of energy through copper. On our way to Rabbit Island, at the Michigan Historical Museum in Lansing we will photograph the Newberry Tablet from every angle. Using macro photographs and lighting techniques to reveal surface phenomena as light and shadows carve forms into two-dimensional digital planes. Using CGI video and copper conductive paintings we will translate the landscape, conflating the objects of water and copper; into a formula for good luck, or narrative about a bird eating grain.

As ‘peak’ copper mining approaches, it seems prescient to consider the scarcity of natural resources including freshwater and copper, both finite and in decline, and actively fought for in the post-industrial environment of global capitalism. The ‘hyperobjects’ of copper (found in home appliances, telephone communications, the internet) and water, both travel along ancient trade routes established in the Great Lakes around Rabbit Island. Local copper is repeatedly melted and reformed. The hydro cycle of the Great Lakes, feeding rivers and aquifers fluctuate cyclically but are also recently subject to dramatic evaporation and increased demand. Six of the warmest years on record there have occurred in the last decade. Lakeside home owners extend their jetties to reach the ever receding water. Freightliners run aground, forcing traders to lessen their loads, losing billions of dollars per annum.

A formula for good luck: Copper conductive paint is comprised of copper sulphate solution (commonly industrially produced for weeding and keeping algae out of ponds), water heated to 70 degrees celsius and ascorbic acid (vitamin C). The local sourcing of which will comprise part of our field research on Rabbit Island. The formula works through suspension of copper nanoparticles in the solution of water. The application of pressure by a metal tool or a press to paint after it has dried enhances conductivity and durability - a process re-enacting the forces of geology itself, making the surface shine with the familiar glow of copper. Utilising of make-shift technologies for electricity in the off-grid context of Rabbit Island, and providing an immediate medium in which to work with whilst providing a form in order to begin constructing the CGI video. Once the paintings are completed we will experiment with different types of circuitry, to make the copper conductive paint perform (i.e. with lighting or sound).

A bird eating grain has the potential to transport plant life in the form of seeds over oceans and expanses of land. It is an analogy and maps out another perspective, an impossible as-the-crow-flies viewpoint of a migrating animal, the trade path of a cargo vessel or an explorer’s ship, a satellite or drone view over the Great Lakes, an electron in a single amp of conductive energy along a copper path, or a camera in a computer generated image. This second translation has the role of the overview perspective and can ascend and cover unimaginable distances over the landscape, its historicities and its ecosystems.

In SURFACE NORMALS the Newberry Tablet is a location in itself, a world-sized object that exists in multiple time-zones, whether an archaeological forgery or a genuine object imbued with narratives of human and material movement. From the off-grid location of Rabbit Island we utilise the natural resources of water and copper to understand the notion of the wilderness and connectivity as a whole.

Mirko Winkel and Martin Schick. Coming from a visual arts background, Winkel (East Germany) has collaborated on several occasions with dance/performance artist Martin Schick (Switzerland). Recent performances have been staged throughout Europe including MANIFESTA 11 2016, the 9th Istanbul Biennial, FRINGE Beijing, and Kiasma Helsinki. Both look to transform and challenge the conventions in theater and public space.

Their statement and proposal:

Our reflections about our new project NATURE POLITICS are the result of our artistic practices: we investigate alternative thinking and acting within contemporary society. We want to transform the social architectures and the control systems and move them into changeable material.

Art is the place where society can be re-negotiated without boundaries, where we can dare to think the impossible and improbable, even to allow those utopias to coexist and to try them out together with an audience. The liveness and liveliness are crucial to our work. Performance is a way of experiencing a proposal. A method that might inspire processes of the real world. Our projects attempt to connect with political, educational or institutional organisms, extending and radicalizing the performative, getting rid of the representational position and have an impact on contemporary society.

We seek to move our work to uncanny places, to environments that provoke unusual questions and challenge them in their functionality and implicitness. Spatial practice is where we meet and this is where the representation becomes a challenge.

NATURE POLITICS

During our residency period on Rabbit Island we plan to construct a new performative work which shall be called »Nature Politics«. This is a practical investigation and a rehearsal for a new performance art work. We plan to build an experimental setup and discussions between living human beings and »natural objects«. The aim of this laboratory on site is to develop a vision for a new society and to design techniques and procedures to make this new society happen.

The French theorist and philosopher Bruno Latour developed a concept of a radical democracy. He wants to leave behind the old opposition between subjects and objects, between humans and non-humans – so called »things«. Things have become hybrids, mixed beings. According to him people and things are extremely entangled with each other. We humans depend on them, they affect us. Together we form collectives with a common destiny. Examples can be found in the medical system: The AIDS virus, the homosexuals, the virologists, the drug – they all form such an association of people and non-human beings. Or: If we look at street traffic: Speed bumps, traffic planners, cars and their drivers form another collective. Or: The Internet of Things. The more advanced the technology, the more things and people are confused.

But we still treat technology as a monster. Monsters are constructions of technical objects, which are regarded as manageable and predictable. This is the figure of the cyborg, celebrated by postmodernism. Hybrids, on the other hand, are mixtures of human and nonhuman beings that are not controllable, which are dynamic. And so they demand respect. Only when we socialize technical innovation, we transform monsters into beings. This also means making them subject to the democratic decision.

However, this interdependence between material and humans is not limited to economic or social progress or technology. Humans have always formed communities and alliances with the surrounding nature, since thousands of years actually. These communities appear to have fallen into oblivion. But maybe through our relational structure with new technology, we can re-access the connection to natural elements. Ecology is all about beings that depend on us, forests, waters, animals.

We must decide on a global scale. In which kind of nature do we want to live? Our world is a huge laboratory in which many crazy people are experimenting. We work on all sorts of dangerous things without asking the involved »things« for consent. The meat and bone meal or the cows were probably not asked for their opinion before it all lead to mad cow disease. In order to realign power structures we must rethink the institutions. The question now is which policy suits this situation. What institutions do we need for democratic nature politics. Who are the new parliamentarians and who the new lobbyists. We need to clarify who is part of the arena. The »parliament of things« might restore the balance between people and nonhuman beings.

Our work on Rabbit Island could be an example for his. First, we want to map all living and non-living beings there – everything in real or approximate numbers. This is the comprehensible society of Rabbit Island. Who might be their representatives? In an inaugural assembly, we will develop a

Charta of the fundamental rights that includes all parties. How does a constitution look like, that includes every fly, grain of sand, bush plant. We develop a fictive script of this first assembly, a portrait of the different parties and reenact possible conflicts. This will be the material for an exhibition with a performative setup, presenting results of this experiment.

The island and our procedure of a fictive listening to the different voices of nature stands exemplarily for a bigger society and a growing interest in wilderness, complex politics and alternatives and performative forms of negation.

Our 2017 program is made possible with support from the MCACA (Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs) and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Our first artist-in-residence for the 2016 program was the poet from Ohio, F. Daniel Rzicznek. Beginning June 21st and ending July 4th, Dan explored the island and surrounding lake, occasionally swatting early-season black files on calm days and seeking shelter from pitched rain on the not-so-calm. His experience was interspersed with a few trout fishing trips on Lake Superior guided by our neighbor and friend across the bay, Scott Hannula, birdwatching around camp, daily chores, and quiet moments afforded by remote island life.

Dan arrived with the singular goal of completing his 365 poem epic “Leafmold”. Over 14 days alone he completed poems 326 through 364, concluding the project with a final poem written in Ohio while reflecting on his residency in the months that followed. The series of poems created on Rabbit Island will be published in a variety of literary journals and publications over the coming months. Dan graciously shared a selection of three with us here.

Dan also offered thoughts on his time in residence in the form of a list, 13 Things, which serves as a candid portrait of island life that will surely enlighten future visitors.

13 Things

If a bald eagle lands in a white pine near camp and checks you out, do not look away.

Keep a record of everything you see, hear, taste, smell, touch, and feel. You’ll want it later.

Befriend the locals. They will save your life and sanity in more ways than you thought possible.

When Andrew casually drops that the eastern side of the island is an impassable labyrinth of forest and rock, he means it.

Be not convinced of your own intellectual superiority to that of black flies.

Existing on the island is the easiest part of the experience. It’s nearly paradise, and therefore not to be trusted. In turn, reentry into civilized society is the most difficult aspect, even if you’re fortunate enough to find rest at the Cedar Motor Inn in Marquette.

Never set an alarm clock on the island, unless for stargazing in the middle of the night.

You can get by for two weeks on four pairs of socks without using the fourth pair.

Be careful climbing backstage at the auditorium. Ask Penny.

Getting water, gathering wood, and drinking tea all use the same muscles.

If it gives you genuine, lasting pleasure and comfort, bring it with you to the island. Books filled that role for me. Vodka, too. And dry-aged salami. Also, maple syrup.

On the island, you are miles and miles from anything you know. And it is okay. It is all right. You will sleep the deepest, quietest sleep of your particular life.

There’s no preparing for it, but your definition of waste will be rewritten.

– F. Daniel Rzicznek, 26 October 2016

Christian Raguse is a local photographer and outdoor adventurer who visited the Rabbit Island School program in early September to help document the students’ experience. This summer’s program received a New Leaders Grant from the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs allowing artists and mentors like Christian to share his knowledge and experience with the students. Christian had been on an previous expedition with Summer Journeys (the partner organization who organizes Rabbit Island School) and had recently started his studies at the nearby Michigan Technological University. This was his first visit to Rabbit Island, but likely not his last.

My time on the island was nothing short of incredible. From the very beginning I felt very welcomed by the people and the environment around me. My experience began with setting a few down-riggers off the back of the Boston Whaler. I was soon introduced to the people of Rabbit Island School as we disassembled two fresh Coho Salmon on the rocky shore of the island. Without nagging technological distractions, I was able to fully engage with the island’s creative community and learn about the natural sciences of Rabbit Island. I took in all that my surroundings and peers had to offer, while telling my own experience-rich story with my camera. Invaluable is one word that I can pin down to the relationships and memories made during my stay on the Rabbit Island.

See his full photo series and read more thoughts about his time with the school and on the island at his website.

The application deadline for the 2017 Rabbit Island Residency program has been extended until Tuesday, 1 November 2016. We have received a flood of last minute questions about our new application system, and are planning to give our selection committee additional time to assess the review process. Take time and send us your best. We are looking forward to seeing your work and proposals.

Download the guidelines and apply at rabbitisland.org/art

2016 Island Notes

The combination of good weather, extraordinary residents and inspiring visitors provided an incredible residency season for 2016. Here’s a recap:

– 2016 Residents F. Daniel Rzicznek, Walter van Broekhuizen, Luce Choules, and the three-person collective comprised of Jack Forinash, Kelly Gregory, and Mary Rothlisberger, were prolific in their work. Highlights include the completion of an epic collection of poems, a number of temporary installations documented via drawing and photography, field experiments, and performances which will be used to create new work for the 2017 exhibition, and a comprehensive collection of data—both of the measurable and ephemeral—related to island life. The island’s journal also saw it’s pages grow as residents documented subtleties of daily life in real time.

– The first year of “Island Talks” went well and we hope to build on this success in the future. Island Talks are our series of informal presentations by resident artists and founders where we invite members of the public to visit the island and experience the residency firsthand. Weather prohibited attendance for a few of the talks, but two were very well attended and received. (Always Respect the Lake.)

– It was a stellar summer of foraging berries and mushrooms. Wild blueberries did best, followed by a respectable showing of raspberries. We also added to our local mushroom knowledge and enjoyed cooking several boletus variants.

– A talented woodworking duo consisting of Tom Bonamici and Anthony Zollo spent time on the island creating furniture for the sauna building and main camp. They were later joined by Michael P. Getz who assisted them in constructing a traditional timber frame structure in Rabbit Bay which will serve as a mainland “Ranger Station” beginning next year.

– Dancer/choreographer Nic Collie and filmmaker Chelsy Mitchell joined us for a week to collaborate on a new video piece that will be completed later this year. Nicola created a series of movements especially for the island's Perch installation situated in the trees along the south ridge. Some incredible underwater movements were also captured.

– Fishing was excellent this year. Neighbors in the bay had some nice catches and we were able to bring in several steelhead, over 40 prized lake trout (mostly caught and released), eight coho salmon, and even a few king salmon that were hanging around Keweenaw Bay this summer.

– Rabbit Island School 2016 continued our annual art and ecology program with high school students in fine style. Record-breaking saunas, countless swims, surfing, cliff jumping, spoon carving, fishing, photographing, art and music making, dancing, campfire chats, foraging, and an incredible back-to-back display of the northern lights are just a few items on a long list of good times. This year the program was supported by a New Leaders Grant from the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs.

– During the whirlwind tour of State of the Union, an opera composed on Rabbit Island in 2015, members of Helsinki Chamber Choir visited the island on their one day off. We recorded a few special moments as the choir sang at The Amphitheater, a forested clearing in front of a large upturned root at the center of the island.

We’d like to say thank you to all involved this summer and to those who support our project from afar. As we unpack the beautiful documentation and stories that were experienced this year we will continue to share details in the coming weeks. Stay tuned.

Calling Dr. Glowacki: Saving Opera from Itself

Composer Eugene Birman likes to say that opera was started by a bunch of elites trying to recreate Ancient Greek dramas in their living rooms. It may have been doomed from the very beginning.

But opera did have redeeming qualities. Before the 20th century it was actually fun. There was booing, hissing, exiting en masse, food throwing, and sometimes even rioting. In the opera house one encountered prostitutes, beer sellers, thieves, businessmen, as well as members of the proletariat. Opera of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries was “live” in the best sense of the word, and it likely had more in common with a World Wrestling Federation triple cage match than with an operatic production of the 21st century.

Not only was opera fun, it did not fear politics. The operagoer got both drama and commentary. Take the works of Verdi. Although a true opera buff might offer better examples, I vespri siciliani depicted the French as evil oppressors, Attila addressed the Austrian occupation, and Un ballo in maschera dealt with regicide.

But something happened between then and now. Eugene likes to blame Germany. After all, it was Wagner who brought us a 16-hour story about a magic ring stolen from a dwarf. Parsifal (only five hours) has a two-hour first act where nothing happens. To attempt to make up for it, Wagner impresarios have had tenor Jonas Kaufmann appear shirtless, and magazine articles are published about why it’s okay to fall asleep during opera.

It seems opera in our day and age has become little more than an upper class ritual, where old white people applaud 200-year-old Greatest Hits by Verdi, Mozart, and Bizet. In “modern” works you get the operas Anna Nicole (as in Smith), Jerry Springer, or Two Boys (about online bullying). John Adams commemorates Nixon for going to China and Klinghoffer for being murdered in his wheelchair by the PLO, making opera more of a monument (something dead) than a vehicle to provoke thought and discussion.

In Florida (God’s Waiting Room) it’s not uncommon to see someone die in a restaurant, and it’s somewhat surprising this doesn’t happen more often at the opera. If young people are present, it’s likely because they’ve been given tickets by their company or have been forced to attend by a humorless teacher. Even in Europe, which has a more active opera scene than the US, the audience usually encountered is largely white-hairs. I once attended a performance of Rigoletto in Tartu, Estonia, with an audience populated mainly by people in their 30s. I thought perhaps the Estonians had figured out how to save opera, but upon further investigation the audience proved to be out-of-work Danes on a “training mission.” Sending them to the opera in Eastern Europe was cheaper for their government than feeding them in Scandinavia.

Opera continues to make itself more irrelevant. Despite efforts by the Met to stream it into theaters worldwide –and I fail to see how a broadcast of an opera can compete with a movie – it seems there is no worse idea than watching a movie of an opera, when the concert down the street offers a mosh pit.

In State of the Union, we’ve tried to remedy all this by writing an opera we ourselves would like to attend, about a topic we believe matters.

Early on we were asked what our elevator speech was for SOTU. I tried: “An opera about everything wrong with the planet…” But the problem here is that there’s actually nothing wrong with the planet. There’s something wrong with us.

SOTU is four characters – the environment, the rich, the middle class, and the poor – meeting and interacting over seven movements. It reflects my belief that many of our problems stem from how we view and treat one another. As a society, at least in the US, we equate wealth with wisdom, and poverty with personal shortcomings. SOTU attempts to offer the perspective of each character, without being so depressing that a concertgoer would go home and kill himself. It offers hope, in its own sobering way.

We also like the idea of this opera being performed somewhere unconventional, that it should not be so easy to access. In an era where music can be downloaded and shared essentially for free, what if some SOTU performances could say something about what it means to be a listener and how to appreciate music?

Eugene has suggested SOTU be premiered on a difficult-to-reach island, where you have to take a Boston Whaler, then a dinghy, and then scythe your way through a dense forest to reach the performance grounds. It would offer an unconventional experience and attract a rather special audience.

We’re not alone in this desire. There are writers, composers, artistic directors, as well as performers out there who also would like to give the audience a better experience. But their efforts are not always positively rewarded.

In 2014, the Bristol Old Vic theater’s artistic director invited the audience to “clap and whoop” during a performance of Handel’s Messiah. One audience member, the scientist David Glowacki, took the director at his word but was then dragged from the theater by audience members when he tried to crowd-surf during the Hallelujah Chorus.

If you’re out there Dr. Glowacki, and you happen to be reading this, you are exactly the audience we want. We hope we’ve created something worthy of your attendance.

Scott Diel

July 2015

.

Hi Scott,

Thanks for sending this through! Sounds like a great piece and right up my street, actually. I really like the idea and your email provided me a hilarious excuse to revisit the circumstances of the whole Hallelujah (praise the lord!) fiasco.

I have no plans to be in the US during the time you say. I did actually briefly consider arranging an excuse to make it across, but there’s simply too much going on at the moment for me to pop over to NYC.

Good luck with it though. We need artwork that directly addresses our potentially catastrophic cultural malaise. If art can’t awaken it, then ideologues like Donald Trump might do it…

You might commission a plant who can turn up at the show with a surfboard and sit in the front row for the duration of the performance; if anybody asks why he’s got a surfboard, he should tell people that his name is Prof. David Glowacki and that’s how he rolls when it comes to classical art forms. I’ve often fantasized that this would be a great follow-up to the whole affair, but I haven’t yet been organized enough to pull it off.

If you do decide to commission a plant please send me a photo of him sitting politely in the front row with his surfboard. Good luck!

Dave

David R. Glowacki

Royal Society Research Fellow

Beau Carey, Rabbit Island

Opening, Friday, September 16th, 5 - 8pm

Goodwin Fine Art

Denver, Colorado

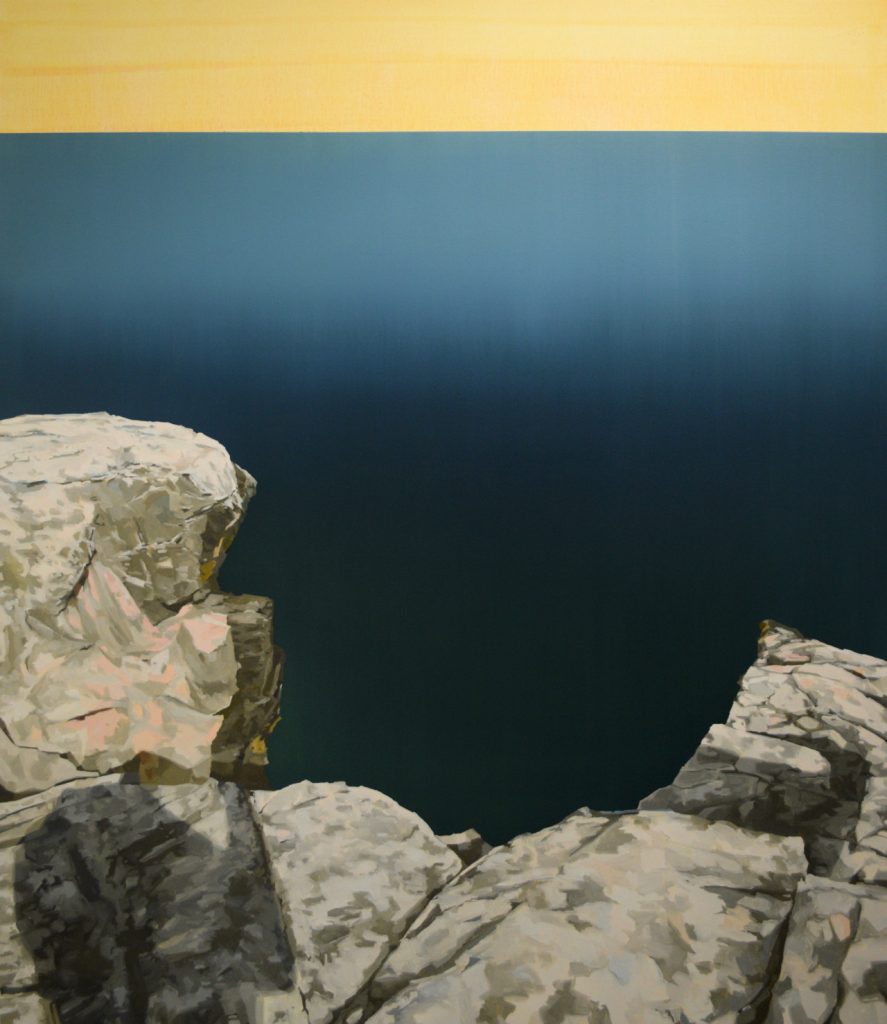

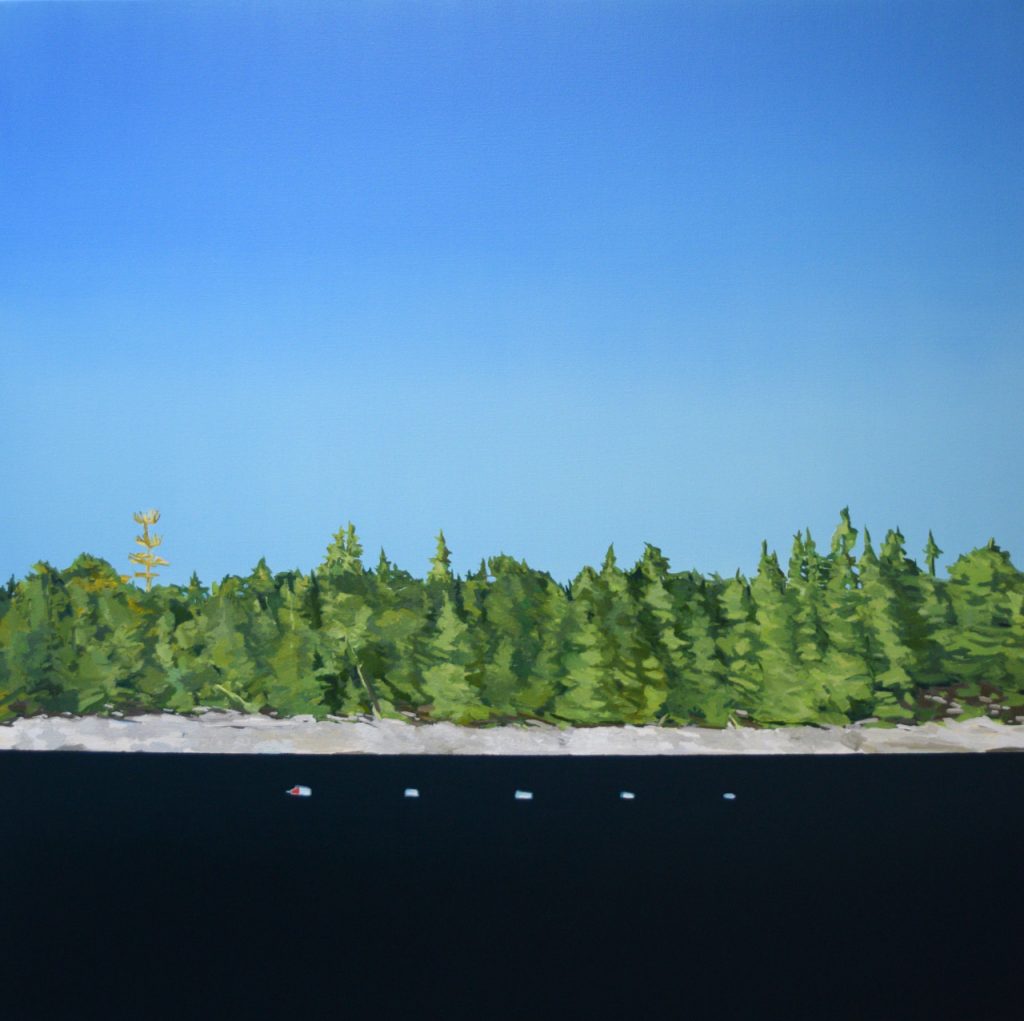

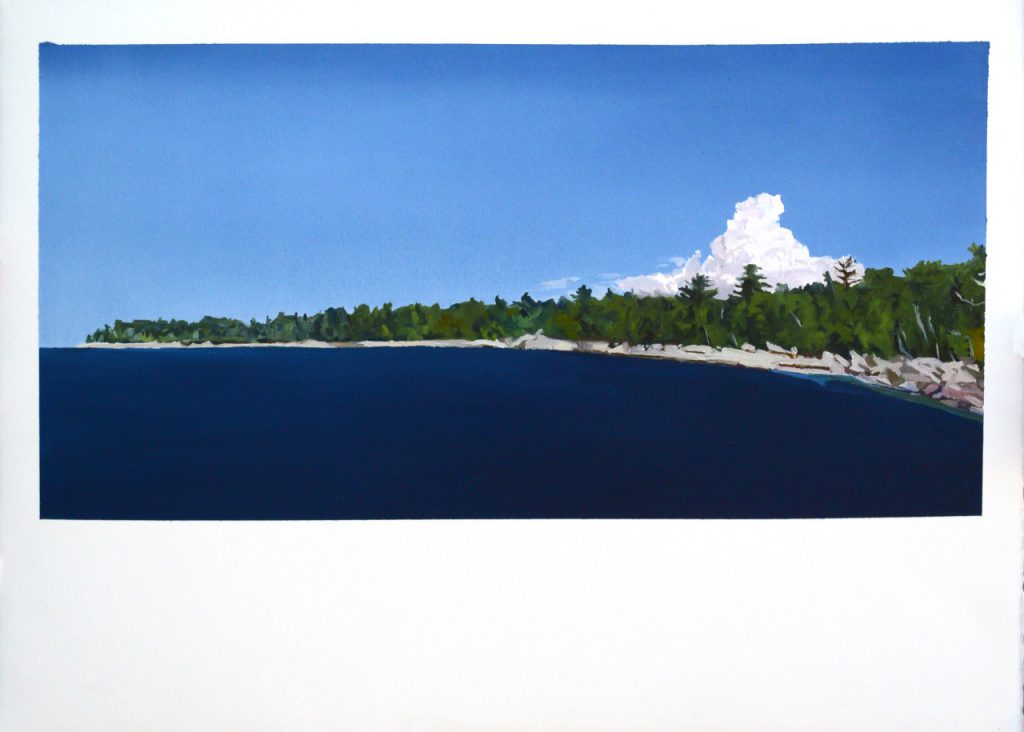

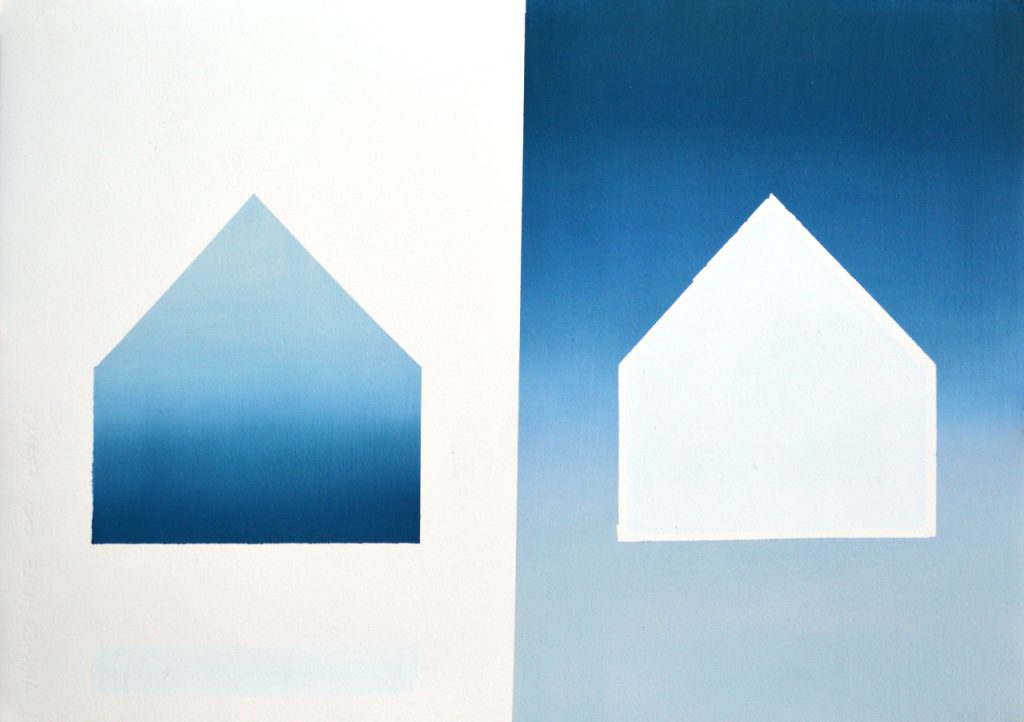

In the summer of 2015 I spent 3 weeks as a resident artist on Rabbit Island, a 91 acre island in the Lake Superior. During the bulk of that time I was the island’s only human inhabitant. I had planned to continue research on coastal profiling and it’s effects on the construction of landscape paintings. However, extended periods of solitude can erode even the best laid plans. As is often the case the primacy of experience overwhelms the mutability of preconceived notions. From the shore, from the trees and from a tiny raft I was able to make a dozen or so oil paintings. These works and the starts of ideas in them became the subject of the following years studio canvases.

Lake Superior feels immensely deep. It also, depending on the weather and the craft you have to navigate it, feels like an insurmountable barrier. In the cliff paintings I raised the horizon line and eliminated surface detail to create a kind of wall/void. Rabbit Island doesn’t have the huge rocky cliffs seen in many of the studio paintings. The island is rocky, but I took certain liberties with scale and surface that better fit with the psychological and philosophical ideas experienced. Standing on those cliffs one is staring into an impenetrable abyss. Other works look at that tiny space between shore and open water by subtly examining views from each position. In them I was reminded of a favorite quote from the 1975 movie Jaws, “It’s only a island if you look at it from the water”. They are reminders that our labels for things are dependent on our vantage points. Together all these works synthesize my experience on Rabbit Island.

Beau Carey, 2016

__________________________________________

July 14th, 2015

9th Full day on the Island

North winds 15 to 25 knots diminishing to 10 to 20 knots by mid-afternoon. Areas of fog this morning. Waves 3 to 5 feet subsiding to 1 to 3 feet.

…Rabbit Island doesn’t need to be mapped, it’s been mapped enough. Any attempt to do so is to see it in parts.

The map is key to sub-division. To see this from that. I own this; you own that.

So what then? How to leave it whole yet comprehensible? In the words of Hakim Bey how do we make the island ‘invisible to the cartography of control’? To remove Rabbit Island from the process of mindless sub-division is in a very real way an attempt to remove it from the map, not as Terra Incognita (Unknown Territory) but as Terra Invisibilis (Invisible Territory)? How do we un-see something? Or how do we leave enough of the right parts to stitch together the right whole?

The above might be impossible or nonsense, the loose, unorganized sketchbook thoughts of an isolated artist on a remote 91-acre island in Lake Superior. As a landscape painter my very task is to divide and omit. I paint this and not that. I condense or expand details according the whims of the genre. I cram the world into neat little squares and rectangles of foreground, middle ground and background. I divide and sub-divide the visual into comprehensible organized space. It is folly to believe that any landscape painter paints the world as it actually is. The history of modern western landscape painting itself is rooted in imperial ambitions and environmental dominance (1), a language of division and sub-division. Rabbit Island is a chance to paint a space that envisions itself as different. The resulting work strives to say something new with old words, knowing the limits of knowledge are the limits of the language. The hope is that the encounter creates a new visual vocabulary.

What emerged was the abandonment of the rectangle as an acceptable format to start a composition. The ‘tondo’ or circular painting, largely a Renaissance tool, was used to leave those right-angled edges behind. Perception is anything but square and with the ubiquity of cameras our vision and experiences are increasingly being squared off, life as an instagram feed, an endless scroll of square memories. So two days into my stay I was tracing the main camps largest frying pan making most of my rectangular paper into circles. The X’s are both a form of division, a measurement, a survey, a reference to what I’m trying to avoid in the square, and they are a negation, a literal crossing out of the painted view. Some of the X’s are exposed under-painting, flat spaces beneath the painted surface that subvert the illusion of deep space that defines the landscape genre. And finally to paint coastal profiles from a boat even in calm glassy water is an exercise in futility. Traditionally profiles were used in navigation requiring a type of preciseness that a moving boat in my experience makes nearly impossible. It was with this revelation in mind that the July 14th sketchbook entry was written. The idea that Rabbit Island doesn’t need to be mapped and profiled at least not in the way it has been done in the past. Those tools lead us to a sub-divided world of haphazard development. What is required is the long project of developing new ways of seeing, of talking about spaces. What is required is more Terra Invisbilis.

Beau Carey, 2015

(1) Landscape and Power, ed. W.J.T. Mitchell