Art + Athletics + Wilderness = Awesome. Artist Sarah Maynard of Oakland, CA, is raising money on Kickstarter for her residency on Rabbit Island this summer titled Building the Ocean. She will be making art and training for a 10k open water swim in Vermont later in the summer. Give her a hand if you can. 18 days to go and she is halfway there. Kickstarter.

Meet the new Rabbit Island ferry: a Boston Whaler 17 Montauk. “The Unsinkable Legend”. May she stay off the rocks.

Field Notes from the 1987 DNR survey of the heron rookery. The effect of time on the island’s wildlife is interesting. It appears the herons have been moving steadily northeast over the last several decades.

+ “Former heron rookery, now cormorants 1987”

+ “Many blown down GBH [Great Blue Heron] nests”

+ “1987 Approx bound. of Grt. Bl. Hrn colony, more nests toward the NE”

Last fall when we drafted the Rabbit Island Architecture Competition we didn’t know what to expect. We only knew that one of the fundamental premises of the project (perhaps the most fundamental premise) was that anything made by man on the 0.3% of island land that would not remain wilderness forever should be approached with foresight, sensitivity to the surrounding ecosystem, and, above all, restraint. Excess, after all, does not imply greater value. This idea of efficient value creation, in the context of architecture, led us to several reference points rooted in the following basic contrast: the vast creative force of man vs. the value of undisturbed nature itself. We believe that the success of the organization of these two subjects relative to one another is paramount, and feel creations that achieve the rare combination of simplicity, utility, and beauty are the most timeless.

With this in mind we approached the competition entries. There were seven solutions submitted in total spanning a wide variety of conceptual references, technical complexity and philosophical tones. It goes without saying that we are beyond thankful and very impressed by each entry. They are listed here as submitted for review.

one + two + three + four + five + six + seven

After deliberations by the jury composed of architects, artists and practicing designers, three groups have been selected to further collaborate on the island this summer. Congratulations to the winners. (Details for the winning designers to follow):

+ Jono Sturt and Thomas Affeldt

+ Mark Moskovitz and William Ransom

The Sturt and Affeldt submission was chosen because of its simplicity and feasibility as well as its conceptual relevance. There is a quiet beauty underlying the team’s designs which openly accept the natural surroundings as integral elements. It is also obvious that the team understands well the limitations imposed by a location as remote as Rabbit Island. Particularly popular with the jury was the platform concept composing the beautifully presented forest studio. And in general we like that the Sturt and Affeldt plan promotes the creation of daily cadence and custom from a broad spatial perspective, involving sunrise and sunset specifically as well as various points along the northwest and northeast ends of the island. This is conceived with a very light, minimalist, touch. We also liked the simple rendering of the bathing and toilet facilities: functional, moveable when necessary, sufficient. We were further impressed by Sturt and Affeldt’s discussion of the island project and metaphorical comparison of it to an “umbilical cord”, transporting “only what is most valuable, nutritious, vital.” This is a concise idea and one that we appreciated. More thorough discussion of this can be found on their submission page. Lastly, the physical manifestation of the presentation itself–two 11’ x 17’ slabs of hardwood fastened together with a cloth binding, containing four folding printed sections inside–also deserves merit and was certainly the most thoughtful submission from that perspective.

Will Holman’s submission was perceived as a relevant and poetic solution that was philosophically grounded. His rock and wood structure relies almost exclusively on island material, is exceptionally simple, and incorporates its ultimate obsolescence into original design. It has built-in history and in the long run requires little if any remediation. This was very well received and novel in conception. The jury did have a few technical suggestions they would have liked to see applied to the design–roof pitch, overhang construction, etc–and some minor qualms with the form, but felt overall that the fundamental idea as submitted was very strong. The stairs were appreciated by several members of the jury as an interesting multi-purpose common area and one member had this to say about the submission in general: “I love the poetics of the idea, and the drawing of the ruins at the end about killed me. His is a pretty brave design proposal–‘here is my idea… here it is after it falls apart’. Balsy.” More than that, it is inspiring. Overall Will’s solution is not only feasible but also successful philosophically and anthropologically. These ideas, more than the aesthetics of the solution themselves, pushed the jury to see great future potential in collaboration. More discussion of the ideas underpinning Will’s design can be found on his blog here.

The Moskovitz Ransom Designs submission was chosen because of its abstract conceptual merits: shelter becomes art. Or shelter as art. Their design was certainly the most provocative of those submitted. Though this proposal did leave some jurors longing for further technical detail and others wishing for variations of the suggested stone forms, the force of its concept was exceptional and relevant. All felt this design was flexible, local, and inspired the mind to wander as much as sculpture as functional shelter. We especially liked the particlelized composition of the general site plan which we felt insinuated the feel of a small village. We also appreciated the water features discussed by the designers intended to complement swimming and dockage. These could be re-imagined with each passage of winter’s brutal ice load across the sandstone shoreline. Overall we felt this duo to be the truest image makers of the group and envisioned the presence of their abstractions, in moderation, changing the context of the site from one of wilderness to one with an inflection of wonder or curiosity, while not detracting from the wilderness itself.

Part Two of the results to follow including discussion of the other submissions and details of the winning designers’ involvement in the project.

Rabbit Island Architecture Competition – Jury Duty

A jury of architects, designers and artists was assembled and began formal criticism of submissions to the Rabbit Island Architecture Competition this past Monday evening. We gathered in a conference room at the WeWork space in Soho and held a lively round-robin discussion. Seven submissions were received in total spanning a wide variety of conceptual references, technical complexity and philosophical tone. Out-of-town jurors are continuing to review submissions and will be summarizing their ideas which will then be added to the consensus of the NYC based meeting.

For reference the original competition guidelines can be found here.

Chris, architect

Monica, architect

Max, designer

Tom, artist

Jimmy, assistant professor of architecture at Copper Union

Melissa, director of the DeVos Art Museum

Leo, partner at LoT Architecture

Amanda, graphic designer at MoMa

Jace, editor of Cabin Porn

Julia, architect

Andrew, artist

Phil, artist and co-founder of Livestream

We will be basing our decision on the objective merits of each proposal alone, while attempting to avoid outside influence. However, as is the case with any jury, we may discover that there is no such thing as an impermeable media curtain. Thus feel free to add bias by ‘liking’ submissions on our blog or facebook page. We hope to have conclusions prepared by next Wednesday.

Submissions are linked here (in no particular order) and can also be found by scrolling through our blog: one + two + three + four + five + six + sevenRabbit Island Architecture Competition: the Hatchling

Submitted by Lindsay Brugger and Christina Kissel

“The Kissel Design LAB was born out of a desire to create innovative and contextually sustainable solutions that enhance the lives of all; believing that it is only through the inseparable qualities of purpose and place that a building becomes part of life’s evolving fabric.”

contact: lbrugger096@gmail.com, cmjkissel@gmail.com

Rabbit Island Architecture Competition: Will Holman

Contact: objectguerilla.blogspot.com

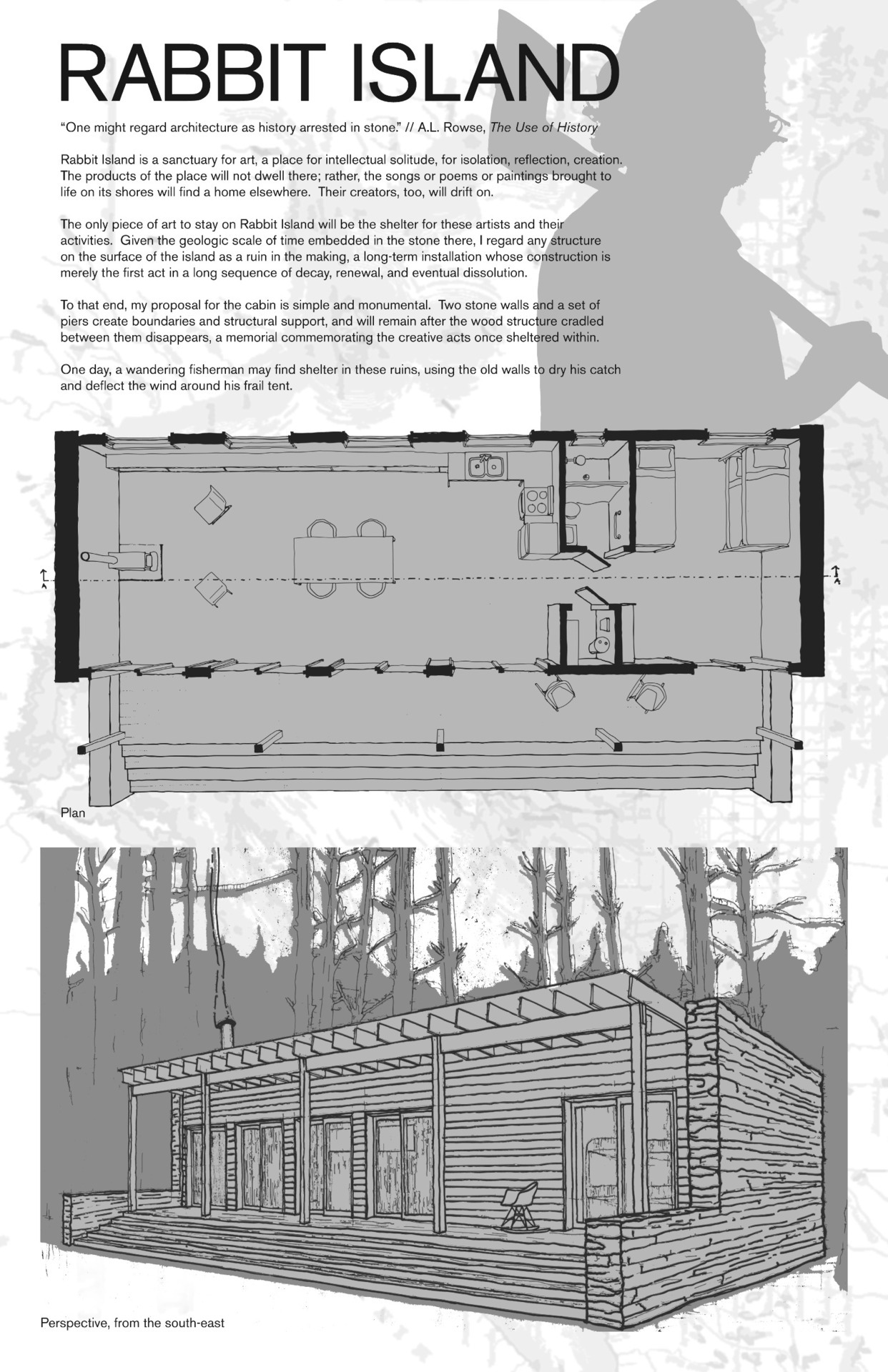

“One might regard architecture as history arrested in stone.” // A.L. Rowse, The Use of History

Rabbit Island is a sanctuary for art, a place for intellectual solitude, for isolation, reflection, creation. The products of the place will not dwell there; rather, the songs or poems or paintings brought to life on its shores will find a home elsewhere. Their creators, too, will drift on.

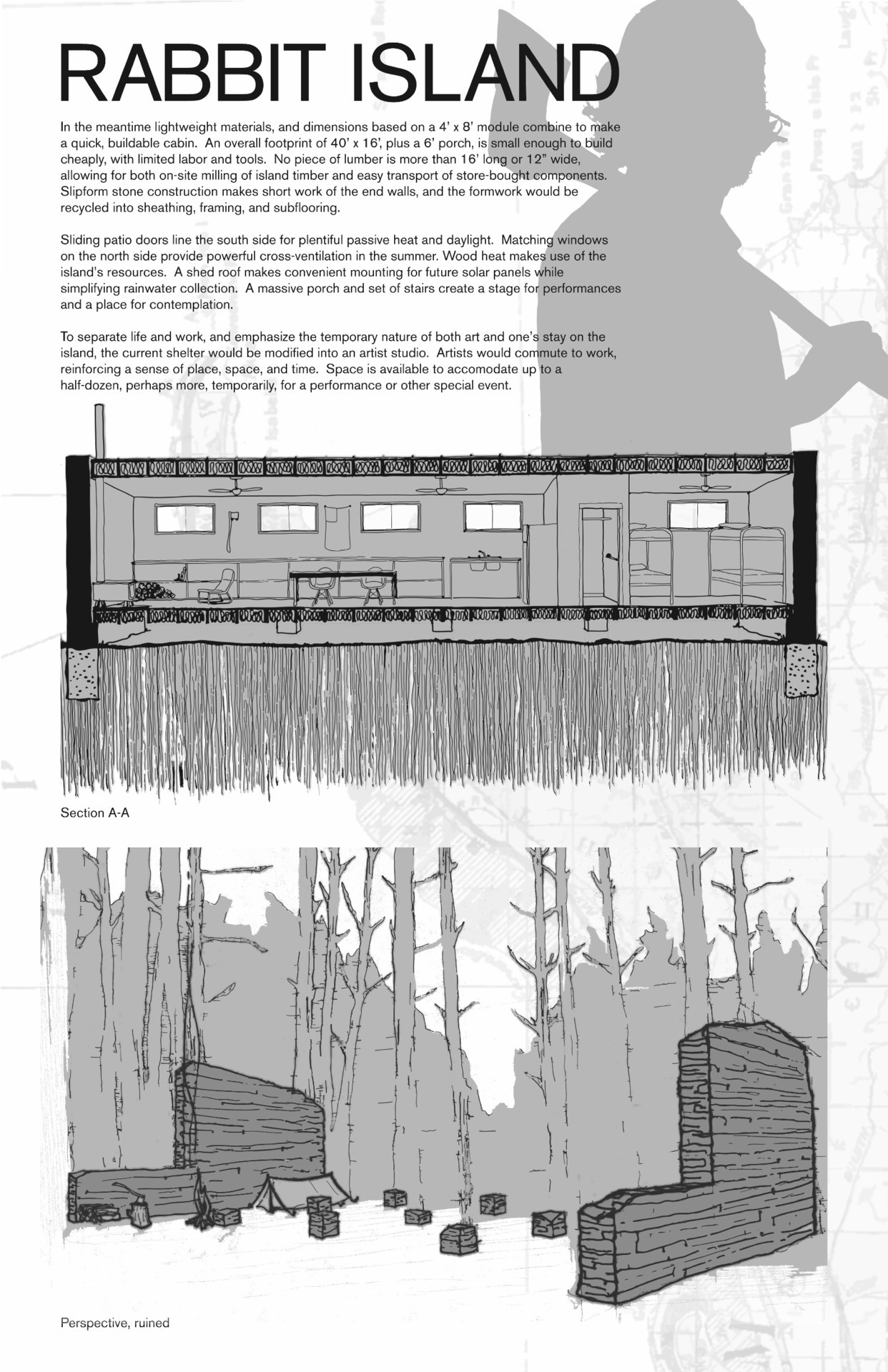

The only piece of art to stay on Rabbit Island will be the shelter for these artists and their activities. Given the geologic scale of time embedded in teh stone there, I regard any structure on the surface of the island as a ruin in the making, a long-term installation whose construction is merely the first act in a long sequence of decay, renewal, and eventual dissolution.

To that end, my proposal for the cabin is simple and monumental. Two stone walls and a set of piers create boundaries and structural support, and will remain after the wood structure cradled between them disappears, a memorial commemorating the creative acts that once sheltered within.

One day, a wandering fisherman may find shelter in these ruins, using the old walls to dry his catch and deflect the wind around his frail tent.

In the meantime lightweight materials, and dimensions based on at 4’ x 8’ module combine to make a quick, buildable cabin. An overall footprint of 40’ x 16’, plus a 6’ porch, is small enough to build cheaply, with limited labor and tools. No piece of lumber is more than 16’ long or 12’’ wide, allowing for both on-site milling of island timber and easy transport of store-bought components. Slipform stone construction makes short work of the end walls, and the formwork would be recycled into sheathing, framing, and subflooring.

Sliding patio doors line the south side for plentiful passive heat and daylight. Matching windows on the north side provide powerful cross-ventilation in the summer. Wood heat makes use of the island’s resources. A shed roof makes convenient mounting for future solar panels while simplifying rainwater collection. A masive porch and set of stairs create a stage for performances and a place for contemplation.

To separate life and work, and to emphasize the temporary nature of both art and one’s stay on the island, the current shelter would be modified into an artist studio. Artists would commute to work, reinforcing a sense of place, space, and time. Space is available to accommodate up to a half-dozen, perhaps more, temporarily, for a performance or other special event.