It’s thundering and lightning as I write this, and I am feeling the same feelings of vulnerability I was feeling this summer while weathering lightning storms aboard my little sailboat. Certain reactions have become ingrained in me after spending hundreds of hours and nearly five thousand nautical miles living and traveling on Lake Superior over the last three years. Rabbit Island was one of the most memorable highlights of those hours and miles, storms, sun, weather, and people.

It came and went three times over before I was able to stay for any appreciable amount of time. I learned of it by chance while my girlfriend was looking up pictures of cabins on the internet. After doing some research on it, and who was behind it, I decided I must go there. It just so happened I had already taken the forthcoming summer off to go on a sailing odyssey on Lake Superior. And so I scribbled out “Traverse Island” on my nautical chart and printed in black marker “Rabbit Island”.

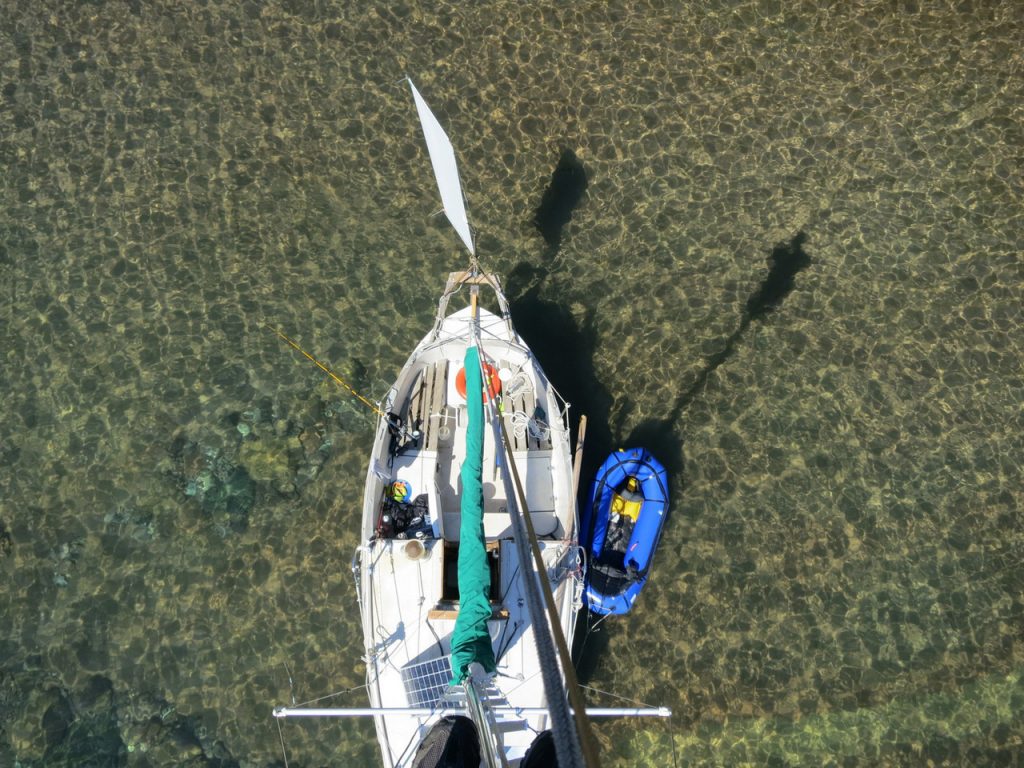

Months passed. I was able to launch my twenty foot sailboat “Voyageur” on March 28th due to the unusual weather patterns that were hovering over the Midwest. Susan and I left Washburn, WI, aboard Voyageur on April 21st and after a few stints at the tiller, a few minor issues, weather, and waves, we arrived through dense fog at Rabbit Island.

But our stay was short. We hiked part of the island, then started a fire in Voyageurs little wood-stove to warm up. The weather was foreboding and the island lacked good protection had a storm arose. The rocky bottom wasn’t good for anchoring, and being April I wasn’t about to dive into the frigid waters in order to get a good set with the anchor. So naturally, we left for Grand Traverse Bay, further North up the Keweenaw Peninsula coast.

Susan, Voyageur, and I continued to sail up the Keweenaw coast to Copper Harbor, then over to Isle Royale and then into Canada, eventually turning to head for home once we had hit the Slate Islands.

It had been two months since that cold and foggy day with Susan on Rabbit Island when I once again found myself battling a headwind, waves splashing spray across my face, trying to reach the island. I made it halfway before turning around and heading back to the Keweenaw Entrance for refuge. A few days later I tried again amidst much better weather.

It was calm and I anchored on the West shore. I dropped my anchor and watched it drag across the bottom, bouncing off rocks, until it finally caught underneath a large boulder. I jumped into the dinghy and rowed ashore.

“Hi! You must be Marlin! Welcome!”

I was greeted by Rob and Ty, and not long after this greeting we got to work on the obvious: a sauna.

But the weather wouldn’t have it and the next evening (after watching Voyageur bounce around in the building waves) I decided to go back to the Keweenaw Entrance and hideout from the impending bad weather. While I was leaving the island and making my way back to the Keweenaw Entrance the waves started to build along with the wind. I noticed a cruise ship traveling North up Keweenaw Bay. I had never seen a cruise ship on Lake Superior and I was sort of dumbstruck, which caused my mind to turn. It was in that momentary lapse of attention, attention which the inland sea was by then demanding of me, that I got caught broadside by a large wave. In an instant several inches of water had collected in the cockpit and I was soaked from head to toe. I arrived back in the South Entrance around midnight.

The days passed slowly as high winds ripped across Michigan’s Upper Peninsula until I once again found myself sailing the ten miles back to Rabbit Island. This time I was determined to stay for more than a day and had decided I would dive down and set up a temporary mooring for Voyageur by jamming my anchor underneath the biggest boulder I could find. This I did upon arriving and the anchor held well over the weeks that followed.

…

Excerpt from the Memoirs of Peter Lahti:

“…the [rabbit bay] district was a veritable wilderness, covered with dense forests—possessed of a wild and somber beauty…” —Helen Torkkola, 1939

We worked on the sauna. We swam. We hauled lumber from the mainland. We built things and shared ideas. Friendships were made and meals shared. We popularized a new gauge of measurement: The Rabbit Island Titsel. We all felt like we were a part of something; because we were a part of something.

Rabbit Islands’ resources have never been exploited. Rabbit Island is a wilderness in one of it’s truest forms. It is now protected from being developed in perpetuity. This is the most important aspect of the island to me, and this is why I went through so much trouble to get there. I wanted to see first hand what one person could do. One person who was driven not by greed, but by the opportunity to save something. Having the self discipline to make a decision based not on financial investments and returns, but instead on the principle of our future, is the art of being human, and right now it’s what we need more than anything else.

So Rabbit Island will remain “a veritable wilderness, covered with dense forests; possessed of a wild and somber beauty…” Forever. The true artists that travel there today create ideas fed by the foundation of the island itself. It’s the true artists, the ones who create not for attention or money but for the emotional rush provided by the creation of art, who exemplify the preservation of Rabbit Island. It is these artists who are preserving the arts, and the art of being human.

- Marlin Ledin

The oral history of the changing Lake Superior water temperatures it is striking.

This chart illustrates one of the warmest days ever recorded on lake superior, July 24th, 2012. It is sad, but well documented, that Lake Superior–the sole remaining ecologically sustainable great lake–is being pushed to new extremes by the changing climate. We’ve been noticing things change on the island.

Many of us involved with Rabbit Island are in our twenties and early thirties and grew up with Lake Superior as long as we can remember. For us it has been significant to witness temperatures on the ‘big lake’ warming, even since our childhoods in the early 80’s. Swimming used to be a challenge back then, even on the hottest days of summer. Now it is tolerable from late June through September. The winters have changed too. Not since the 1970’s has ice stretched all the way between Rabbit Bay to Rabbit Island and long gone are the tales of strapping on ice skates after a calm freeze and gliding over three miles of ice to the island, around, and back. Also gone are the stories of packs of coyotes stranded on the island after having crossed ice bridge which blow offshore.

For the generations before us the changes are even more amazing. We can only imagine. What was this like? How have things changed?

If you are of an earlier generation and have a personal account of the changing lake please consider sending it along or posting it on our facebook page. We’ll add each story submitted to the archive below for the sake of posterity.

Decades or centuries from now the island will continue to exist in its natural state, though the nature of the land and surrounding lake may be of very different character. It is possible that the climax forest community may drift. It is possible that balsams will give way to birches or maples. One can only speculate. Regardless, it will continue to be interesting to read the observations of those who witnessed such events unfold over the frame of reference of a lifetime.

+ NOAA real time graph of Great Lakes surface temperatures

+ The lake is a brisk 52 degree around the island today, October 24th, 2012.

+ This season we swam to hang the moorings near camp on May 15th and swam again to pull them on October 1st.

+ There are many related articles on this subject. Some of the more interesting first person comments from the one we have linked have been copied here (and edited slightly for clarity) and added to others which have been submitted:

As a life long resident of the North Shore of Lake Superior, I can tell you that the beaches are full of kids and adults taking full advantage of the fine swimming conditions. When I was a kid in the 1960’s, a dip in Lake Superior in July would be life threatening. A game we played in summer was to have 4 or 5 kids stand knee deep in the lake and see who could stand it the longest. The cold gave unbearable pain and few kids lasted more than a minute or two. It has been decades now since we had large ice cover of the lake in Winter. I can not remember the last time open water froze over; the harbor freezes up some years but never the open water. Again, when I was a kid the lake froze up every winter. Large Ice Breakers worked in April and May to open shipping lanes. In the 1970’s we had ice conditions on the 5th of June. Now we no longer have Ice conditions in January! To anyone living decades along the Lake Superior Shoreline, climate change has been undeniable. The warming has been extreme and rapid over the last 20 years. That is why nobody around here goes for the climate change denial story. When you live it, it is hard to deny.

I just went for a swim in Lake Superior in the warmest water I have ever experienced. The North Shore is like bath water. It is not even August yet! If the heat and sun continue as they have, we will break the record warm water temps by a massive amount. I would bet my life we don’t see a piece of ice on the lake this coming winter. In the past, lake superior water would kill you in minutes, even in summer, now we all run down to the beach and jump right in. I saw long distance swimmers training far out in the lake today; this was unheard of at any time around here.

During the hot summer of 2010 I spent four consecutive hours immersed in Lake Superior (hunting for just the right stones for finishing prizes for the Marquette Marathon). But, like noted above, when I was a boy being in the big lake for more than a few minutes was unthinkable. Now the beaches are flooded with people, in and out of the water.

I remember the water being really cold in the 1950’s–freezing cold. When you first went in you thought your feet might turn blue. You just had to take the plunge. After being in for a while you would get used to it but pretty soon had to get out and lie on the rocks to warm up. And you could only swim for a few weeks at the end of July and early August. That was the swim season. The water was much clearer back then too.

I was born on the shore of Lake Superior in 1953. During the early 1970s, I paddled a canoe on Lake Superior during early June encountering icebergs. For the past 12 years, my brother and I visit our cabin each March with a goal of skiing on, or on the shores of, Lake Superior. For most of the past 5 years, we’ve kayaked on the Lake as the ice has moved out. One year, my brother swam in Lake Superior as the 60 degree March temperatures were quite warm.

Rabbit Island Quadrangle by artist and cofounder Andrew Ranville.

The official Traverse Island quadrangle represents Rabbit Island at the classic 7.5-minute, 1:24,000 scale which all quadrangles across the United States were mapped at. It was field checked by the agency in 1954 and further revised using aerial photographs in 1975. While it does place the island in the context of Keweenaw Bay it provides little detail of the island itself.

The mapping of the United States by the 7.5-minute topographic maps—the most detailed of the quadrangle series—was an immense and impressive undertaking, championed by an equally impressive man: the second director of the USGS, John Wesley Powell.

Unfortunately, those iconic topographic maps are no longer being produced by the USGS and the program was “completed” in 1992. Now US Topo maps are the future, though they are inferior in terms of both aesthetics and function. The new US Topo/National Map quadrangle of Traverse Island actually cuts the north shore of the island completely off.

My intention was to map the island at a much more detailed scale than the historic quadrangle maps and publish it as an artist’s print, in an edition in collaboration with the USGS themselves. Unfortunately the same budget cuts and congressional pressure which brought about the poor US Topo map series resulted in a curt response. Undeterred, I continued gathering data via circumnavigations, transects, and waymarking over 2012, adding to the data I collected in 2011. Illustrating the map from scratch, I completed the first version in early September. Thus the island can now be seen at 1.5-minute series (1.5 degrees of latitude and longitude) at a scale of 1:4,800. The printed edition—unlike the digital version provided above—contains markedly more details and waymarks.

Map logistics were a challenging issue. In the end one of the most instrumental people in making the map a reality was an actual USGS employee, Doug Thomson. He formerly ran the lithographic printing press at the USGS headquarters in Reston, Virginia, and provided invaluable technical advice and support including Pantone color translations to match the original inks with the spot colors used in the print.

To honor the tradition of the classic topographic maps I had the map created lithographically on paper closely matching the color, weight, and feel of original maps. Jack Eberhard and the staff at Book Concern Printers in Hancock, Michigan were unflappable, working down to the wire to have the map printed in time for the No Island is a Man exhibition.

The final result is an edition of 275 maps at 16.25" x 24" (approx. 41cm x 61cm), five spot color on 70lb NewPage Anthem matte coated stock.

These limited edition prints can be purchased online by donating $40 to support the Rabbit Island residency program.

+ Available here at our online shop

While I view my cartographic research on the island as an extension of my arts practice, I greatly appreciate the practical and scientific value this work presents. I hope it will provide a valuable resource to future researchers and artists, and serve as a lens that further-afield friends and acquaintances can use to experience the island in some small way. The map is not exhaustive, it would be foolish to attempt a map that was. After all, some things are best left to be discovered first hand.

–Andrew

Photos from Andrew Ranville’s exhibition No Island is a Man currently showing at the DeVos Art Museum. More on how you can get your hands on limited-edition maps, catalogs, and artifact kits soon.

The exhibition runs until December 14th, so head on over and check it out if you’re in the area.

Also check out Andrew’s artist talk at the university’s media site. (Download the plugin to view it.) The Rabbit Island discussion starts about halfway through.

Field Research Notes:

Well, I finally made it to the island. It’s obviously a great place! Superficially it has some differences to the mainland which are interesting. I find it reminiscent of the Pacific Northwest: the extensive arboreal lichens, sphagnum, and notable lack of decomposition (absence of fire?). Not that you don’t see this on the mainland, but it seems more pronounced on the island.

As you mentioned there are Peromyscus on the island. You’re also probably aware of the least chipmunk. During our visit we placed 50 Sherman live traps in a rather tight pattern. (If traps are widely dispersed captures rates usually increase because a greater number of home ranges are represented.) On the first night we captured 14 red-backed voles. In the “north woods” a 28 percent capture rate with low trap dispersion is a high number. This could be the results of inter-annual fluctuations. Alternatively, it could be due to lack of terrestrial predation.

I recently had an interesting conversation with Buzzy Butala (a long time Keweenaw guide, hunter and trapper). He described how fisherman used to drop him and his buddies off on the island in the morning and pick them up in the late afternoon. During the day they would “easily” shoot 40, 50, or 60 rabbits. This again suggests high numbers of mammalian prey. He also added that they were often “scrawny little things” compared to the mainland, further suggesting little to no terrestrial predation and food limitation.

This leads to some questions about research projects. One potential project would involve a genetic analysis of the red-backed voles. Does the island population show a reduction in genetic variability as compared to the mainland? Is there evidence of molecular divergence from the island population compared to the mainland? The lack of replication (only one island) is an issue, but there are ways this might be handled. My question initially is; would killing 30 voles be acceptable? I’m not sure how this fits in with the vision of the island or the conservation easement. A second possible project would involve foraging behavior and predation risk, using an island-mainland comparison. We use trays with sand and seeds to measure what’s referred to as a giving up density. This is a density of seeds eaten by a mammal in a subscribed sample area providing a reproducible measure of when individuals cease using a resource. The risk of predation can influence the giving up density and inferences can then be drawn as to population dynamics.

These two projects would be dependent upon graduate student interest, meaning it could happen next month or perhaps down the road. If a graduate student does express interest, I (or they) would then provide detailed research proposals. Before proposing either of these ideas to a student I wanted to make sure the general concept was acceptable.

There is a third potential project that I would be interested in pursuing myself. A comparison of vole–and possibly rabbit–population dynamics on the island vs. the mainland. This would be a long-term study: five years minimum; ten years would be good. This project would involve mark-&-recapture (live trapping) of voles and rabbits for one week every year. Again, there are challenges that would have to be overcome. For example, will hunting ever be allowed on the island? Rabbits are notoriously hard to live trap and this would obviously have some effect on the population. Trapping grids would have to be established, etc. This wouldn’t require trails but when the lines are traversed it will leave some signs of human activity through a portion of the dense island vegetation. I would also need to identify a mainland reference site. Preferably one that has vegetation similar to the island that is not heavily impacted by humans.

Cheers,

John

+ This is exciting.

+ Interesting study proposals.

+ We encourage the study of Rabbit Island. See the Rabbit Island Science Foundation discussion for more information.

+ Creating an environment where human activity exists and is fulfilling but does not detract from the baseline biologic potential of the land will be an interesting practical and symbolic experience.

+ Lake Superior has just had three of the warmest average summer surface temperature trends on record–a historic change.

Cabin-Time: Rabbit Island @ MISCELLANY opens tonight in Grand Rapids, Michigan. 6pm!

+ photos via Colin McCarthy and Cabin-Time

Andrew Ranville’s show of work created on Rabbit Island is now open at the DeVos Art Museum on the campus of Northern Michigan University. The exhibition is curated by museum director Melissa Matuscak and will be on display until December 14th. This represents the inaugural annual show of work produced by artists on Rabbit Island.

The accompanying exhibition catalog contains discussion of Ranville’s work by the artist as well as essays contributed by curator Melissa Matuscak, art historian and writer Nadim Julien Samman, and Robert Gorski. A limited edition handmade catalog with laser-cut hardwood binding has been created to celebrate the Rabbit Island + DeVos Art Museum collaboration. More information on this edition of 50 will be available soon. Below is a .PDF version of the text.

+ No Island is a Man: Exhibition Catalog

Just as John Donne reported his discovery—that “no man is an island, entire of itself,” but “a piece of the continent, a part of the main”— so could Thoreau announce that “the smallest stream is a Mediterranean sea.” In the particular, macro potential is revealed. Comprising just 90 acres of undeveloped land surrounded by 31,700 square miles of water in Lake Superior, Rabbit Island is a utopian attempt to colonize our imaginations. In establishing this project the artist Andrew Ranville and his collaborator Rob Gorski stake their claim to an ancient Western cultural tradition—one that invokes the island topos to negotiate relationships between the real and the imaginary, utopia and dystopia, selfhood and otherness, center and periphery. In so doing, the Rabbit Island residency also deploys the trope of the shipwrecked sailor, separated from his contemporaries, who must make the world anew. How the world is (re)made—which elements are to be carried over from the past and which are to be discarded—constitutes the moral or political import of productive isolation. - excerpted from the catalog essay Future Islands by Nadim Julien Samman