Congratulations 2019 Residents

We are excited to announce awarded residencies for the 2019 Rabbit Island Residency program. We awarded three successful applications featuring a total of six artists. Each will live and work on Rabbit Island this summer.

Colin Lyons

Elias Sorich and Lucas Rossi

The Religion (represented by Lindley Elmore, Morgan Vessel, and Keegan Van Gorder)

Our 2019 open call received 253 applications representing individuals and groups from 25 countries.

A six member selection committee comprised of Rabbit Island alumni and administrators democratically chose the awarded residents. During February and March each committee member read application texts, reviewed each work submitted, and followed each web link provided. On many occasions members also independently researched previous works online.

Following this process the committee met via videoconference to discuss applications in detail and initially shortlisted 52 applications. After further discussion a refined list of 17 was selected. The committee then took two additional days to review those collectively shortlisted applications and chose 13 finalists who were interviewed for 25 minutes during videoconferences in late March. Finally, the committee members voted anonymously for their top three applications, resulting in the awarded residency positions. The Rabbit Island Foundation is extremely fortunate to have such a committed group of alumni who enrich and advance the residency program.

Below we are sharing the awarded proposals in full. We do so in the interest of transparency, archival intention, and to provide insight into the quality, critical nature, and ambition of the proposals we receive. We do so also fully understanding that the questions, research, and work put forward will likely change in time for each artist before, during, and after the residency. We look forward to working with the residents as their ideas evolve.

Since its inception in 2011 the Rabbit Island Residency program has awarded 26 supported residencies and hosted over 70 collaborators. Our open calls have received over 1300 applications highlighting artwork and ideas that critically engage issues of conservation and natural spaces. With the contemporary challenges society faces we are excited to have Rabbit Island’s residents contribute their research and work to this larger conversation.

The committee extends a sincere thank you to all the applicants. This year’s selection was extremely difficult given the large number of thoughtful proposals supported by exemplary work. While we regret not being able to offer more residency positions, it is an honor to be working with the following artists over the next year.

The 2019 Rabbit Island Residency Selection Committee

Julieta Aguinaco, 2017 Resident

Sarah Demoen, 2017 Resident

Jasmine Johnson, 2017 Resident

Calvin Rocchio, 2018 Resident

Rob Gorski, M.D., Cofounder

Andrew Ranville, Cofounder

Colin Lyons

Biography

Colin Lyons was born in Windsor, Ontario in 1985, and grew up in Petrolia: ‘Canada’s original oil boomtown’. This experience has fueled his interests in industrial obsolescence and sacrificial landscapes. Lyons received his BFA from Mount Allison University (2007) and MFA in printmaking from University of Alberta (2012). He has presented 25 solo exhibitions and site-specific installations across Canada and the United States, as well as in group exhibitions internationally. His projects have been supported by the Canada Council for the Arts, Conseil des Arts et des Lettres du Québec, Alberta Foundation for the Arts, The Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. In 2016, he was awarded the Grant Wood Fellowship at The University of Iowa, and in 2013 he participated in the Kala Art Institute Fellowship in Berkeley. He currently lives in Binghamton, New York, where he is an assistant professor at Binghamton University (SUNY).

Artist Statement

My recent work considers preservation in an age of planned obsolescence and resource depletion. Deeply rooted in historical printmaking processes, these projects consider sacrificial landscapes through the lens of geo-engineering, urban renewal and brownfield rehabilitation. My experiments evoke an alchemical creation of time, memory and historical aura, as I propose new models for how we might memorialize and honor our collective history by re-integrating ritual and enactment into acts of remembrance.

Recently, I have begun developing a printmaking-based installation titled The Laboratory of Everlasting Solutions, in which I adopt the role of a practical alchemist, exploring the intersections between alchemical philosophies and contemporary climate-engineering technologies. The resulting laboratory will imagine fictitious and highly impractical prototypes, which allow brownfield remediation efforts to fuel monumental ideas about our collective future. The laboratory’s architecture may hover between a medieval alchemist’s laboratory, contemporary sustainable infrastructure, and ruin folly.

Proposal

I hope to work in the isolation of Rabbit Island to immerse myself in a 4-week hermetic durational performance, scribing an acid-based illuminated manuscript that will become a core part of The Laboratory of Everlasting Solutions. Throughout the Cold War, cloud seeding and weather modification programs gained broad bipartisan interest and concern, leading to several commissions on the technology. Throughout the residency, I will work to transcribe one of these congressional documents using a diluted solution of sulfuric acid as my pigment, punctuated with illuminated diagrams of Solar Radiation Management proposals. While the texts and images produced through this ritual performance will initially be invisible, they will reveal themselves over the next several decades as the acids discolor and eat away the paper, and the urgency around these technologies intensifies. The opportunity to produce this work within an isolated and unbuilt environment will help to inform the question of what exactly we strive to return to or approximate within a techno-solutionist future; a stark contrast with the sacrificial landscapes I typically work in. Throughout the residency, a daily ritual of exploring, collecting, and sampling will be followed by the hermetic and esoteric process of nightly transcription.

At its core, the science of geo-engineering attempts to mimic, accelerate, or amplify natural processes of carbon reduction using highly invasive means. These strategies form a dystopian contingency plan which, employed alongside mitigation efforts, strive to preserve a close approximation of our present ecosystem. However, instead of practical geoengineering prototypes, The Laboratory will present a future-oriented satire: time capsules which project a vision of the near future based on the realities and anxieties of the present. In their quest to transform base materials, alchemists sought transmutation towards a purer, more divine state. The notion that we might find salvation in the fine balance of strategic chemical spills defies belief in the same way the quest for a philosopher’s stone once did. However, within this critical debate, my role as an alchemist enables me to embrace impossibility, proposing prototypes which are symbolic, rather than practical, so that we may ponder this dilemma through a more philosophical lens.

Elias Sorich and Lucas Rossi

Biography

Elias Sorich is a poet based in New York City, where he is pursuing a M.F.A. from Columbia University. He will be working as the Print Managing Editor of the Columbia Journal over the next years, and is currently a newsletter tinkerer in an administrative office, and a once-a-week writing teacher for a class of Armenian high school students. During the summer he will be traveling to Yerevan, Armenia to teach a workshop based on Folklore, Fairytale, and Myth. His work has been published in a handful of small but pleasant magazines.

Lucas Rossi is a writer living in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He will be pursuing an M.F.A in poetry at the University of Oregon beginning in the Fall of 2019. He works in a number of mediums in the arts, with projects involving poetry, prose, visual art, and music. He also really likes bugs.

Artist Statement

Elias’ work focuses largely on internal states of being, on the flux of emotions, and the instability of thoughts as they stew in the midst of living. I write to these questions with external gestures, I blend the borders between perceiving and being. The world inside is tied inexorably to the world of salamanders under rocks, toads overlooking the backyard stream. In this soup of internal-external figuring, I am a presence, a present figure–not a primary actor.

Lucas’ poetry involves both traditional formal aesthetics and a more contemporary green poetics, emanating from vegetarian upbringing as well as latent guilt in certain childhood experiences: failing to keep moths that I brought home from class alive, or carelessly flushing hundreds of ants out of our house’s concrete patio with a garden hose. Those microcosmic images, coupled with a larger awareness of impending climate catastrophes, define the focus of my work.

Proposal

Through a series of engagements with the bug life natural to the ecosystem of Rabbit Island, the two poets in this collaborative group will write towards the biomass that exists in, around, and beneath the ground they walk on.

From John Donne’s “The Flea,” to Heide Erdrich’s “Stung,” to Michael Dickman’s “Flies” there is something of a history in poetry of using insects to represent the human soul, its vices and virtues, and human thought processes, its pits and heights. Present in our work to date is a respect for, and embrace of, this relationship, and paramount to our aims for the Rabbit Island residency is the desire to embrace it further. We will explore new complexities of this literary relationship, particularly those brought on by the threat of global climate change, and the possibility of mass insect extinction. Through the opportunity to write in and around an environment at least mostly unadulterated, but that is in some larger sense threatened, we will explore how the subtle things in the natural world that make it function, impact the process of internal human undercurrents. What changes between the human and the nonhuman when the hyperobject of global warming casts a long shadow?

Our work during this residency will inspect the notion of the ecological catalogue. How do you make a living register? Account for the vitality of a species? What is lost when data does not retain the felt sense of inter-species contact? As two poets who write in harmony and conflict with one another, we will make a prismatic exploration of a freshly threatened population. Through our words, written on paper and expressed in other mediums, we will go after those elements of living left uncaptured in the environmental accounting of insect life. This will not be a simple chronicling of the insect population, but an attempt to create work that engages with these vital creatures in a more holistic sense. We will write towards them and away from them, a hum in the background, a bite on the skin, a leftover wing.

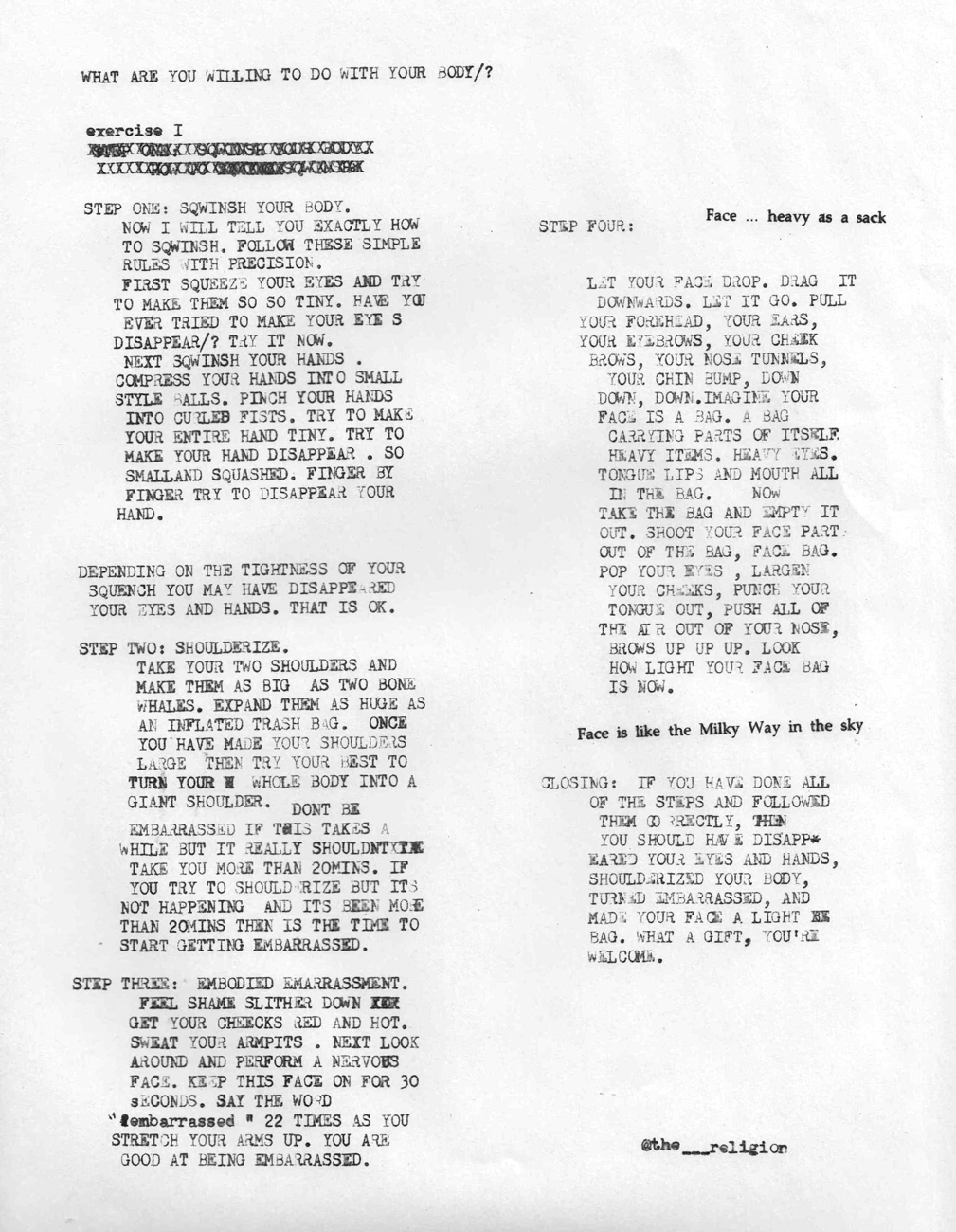

The Religion (represented by Lindley Elmore, Morgan Vessel, and Keegan Van Gorder)

Biography

The Authority Body of The Religion has appointed three trusted members of The Unclogged to practice and pass on our sacred teachings — Lindley Elmore, Morgan Vessel, and Keegan Van Gorder. The three have since shed their academic accolades and moved past their box topics (Sociology, Fine Art) and towards the One True Only Truth. Since their unclogging, their qualifications and markers of success are almost too vast to mention — practicing advanced ceremonies such as Nail Clipping Ceremonies, Grump Code, Fork Follow, Opera Plant Clipping, Exercises in Inefficiency, Housewarming Ceremonies, Selfishness Ceremony, Black Walnut Ceremony, Museum Walking Ceremony, and Making an Old Place New. While Lindley, Morgan, and Keegan live and operate in Minneapolis, The Religion continues to seek new members, collaborators, and dib-dabblers as they grow their body globally.

Artist Statement

The Religion is a project and community of people who are seeking to cultivate curiosity and goof through the creation of new events and experiences. The Religion is a set of beliefs that prioritizes Goofwork, making the profane sacred, materializing ideas and the use of Ceremony as a medium. Ceremony, the Religion’s core practice, helps us access the divine, asks us to try new ways of spending time, lets us re-examine our personal priorities, aims to stretch our stone-set comfort routines and encourages us (The Unclogged) to relearn how to value an experience for the sake of an experience. Ceremony is a tool that allows us to externalize questions, personal themes and new ideas through experiences that are deliberate, extensively planned step-by-step events or spontaneous, wild, improvisational idea-actions.

Proposal

The Religion’s practice asks us to consider our relationship to our socio-cultural environment and physical landscape. Our use of Ceremony encourages inquisitiveness and play through the investigation of place and our position within a larger regional space and social context. We’ve investigated community spaces through public events such as Silent Midnight Trash Bag Walk and Freedom of Information Booth at MSP-St. Paul International Airport. Our work seeks to disrupt the regular-ness of routines and everyday spaces (park / airport) through thoughtful, provocative new styles of re-engagement using movement, constructed legitimacy, ceremony and goof. Since the practice and creation of Ceremonies are heavily informed by our own context and physical environment, much of our ceremonies are centered around urban landscapes (Trash/Treasure Goose Chase, Landscape Investigations I and II, Museum Walking Ceremony), the modern workplace (Undercover Worse than Normal Employee), and happenings in our own lives (Heartbreak Parade, Tinder Ceremony, Ceremony for Fresh Eyes in an Old Place, Ceremony for Moving Out). Experience in past residencies – putting ourselves in new and different places has allowed us to engage new site-specific ideas and produce ceremonies from those locations (Cracking the Eggshell of Winter from our first winter residency in Minneapolis). We want to continue this focused collective investigation of local space in order to write new ceremonies, create community events and develop ideas that are inspired by and extracted from place. We wish to seek out spaces different from what we’ve been afforded in the past in order to engage, and export new topics and questions interpreted from that environment.

Through this residency we want to explore and produce new Ceremonies of differing scales. We wish to compose small ceremonies for our intimate collection of three, ceremonies for our mailed subscribers, and a final site-specific ceremony for the community near Rabbit Island. We wish to further investigate what influences and informs our work, especially the context of place. Our goal is to develop a relationship with Lake Superior, create a ceremony that is specific to our experience on Rabbit Island, and host the ceremony as an event for a small group of people.

2019–2020 Choreographer and Composer Program Awarded Residents

We are thrilled to announce choreographer Yoshito Sakuraba and composer Na’ama Zisser have been selected for the inaugural Rabbit Island Choreographer and Composer Residency, hosted on Rabbit Island in partnership with the Rozsa Center for the Performing Arts at Michigan Technological University. This new concept-responsive residency invites one choreographer and one composer to collaboratively create a new work while living on Rabbit Island in June and July, 2019. In 2020 the commissioned work will be developed out of this immersive wilderness experience with assistance from the Rozsa Center and premiered as part of the venue’s Presenting Series season in 2020–2021.

The Choreographer and Composer Residency is a new medium-specific initiative intended to encourage bold creative experiments that respond to the dominant ecological theme of our day—the environment and the human relationship to it. The program is founded on the presumption that the current canon is insufficient in celebrating the new environmental narrative. We believe there exists a more meaningful way to juxtapose the mediums of dance and composition to the ethics, emotion, and logic of the Anthropocene. These two artists were chosen based on their intention to exemplify this concept as well as the quality of their previous artistic efforts.

A total of 50 applications were received for the inaugural Choreographer and Composer Residency program. The Selection Committee reviewed each in detail, creating a shortlist of 24, and then interviewing 6 finalists. Ultimately two residency positions were awarded. We would like to thank each artist who submitted proposals and regret not being able to offer more positions.

The 2019–2020 Choreographer and Composer Selection Committee

Eugene Birman, Composer, 2015 Rabbit Island resident

Nicola Collie, Dance Artist, 2016 Rabbit Island collaborator

Rob Gorski M.D., President, Rabbit Island Foundation

Mary Jennings, Director, Rozsa Center for the Performing Arts

Libby Meyer, Composer, Director of Music Composition, Michigan Technological University

Andrew Ranville, Director, Rabbit Island Foundation

Na’ama Zisser is a London-based composer originally from Israel, where she grew up in an Orthodox-Jewish background before moving to the United Kingdom. She recently completed her doctoral composer-in-residence with the Royal Opera House and Guildhall School of Music & Drama where she composed a newly commissioned opera MAMZER/BASTARD, the first opera to feature and reference Orthodox-Jewish Cantorial music with a role written for a Cantor. Na’ama has composed for and worked with a long list of groups including the London Symphony Orchestra, London Contemporary Orchestra, Aurora Orchestra, DanceUK, and Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra. Her work has been performed at various venues that include a number of prominent performance spaces throughout London, and has been broadcast on the BBC and other radio outlets.

Artist statement

My work is visually driven and often collaborative with other art forms; with a focus on opera, contemporary dance, staged performances, film and instrumental music. My music is concerned with intonation, textures, repetition, intimacy and nostalgia, and has been described as ‘free of cliches’ (The Guardian) and ‘hauntingly melodic’ (the stage). I have always been interested in the use of musical found material, drawing upon my surroundings and personal experiences. I am interested in telling stories, and often push myself to deal with questions of identity and emotional authenticity in the cultural landscape I operate in.

Proposal excerpt

The concept-responsive nature of the Rabbit Island residency suggests a context to research and realise a work which at the core of it lies a personal, direct human experience; one which is universal, current, and relevant. This is most important to my work, as it signifies a step towards breaking the conventions of the old-fashioned romantic model of the composer in the ivory tower. Allowing me to connect myself with nature and the environment around me, and to let these organic, intuitive experiences manifest themselves through the collaborative process. Due to the lack of suitable support and resources, this model of collaborative process is normally unavailable to us as composers. It requires an honest desire to think and work in new ways which are completely outside of my comfort zone, whilst allowing the space and time to sensitivity tailor a custom-made work, not limited or restricted to any specific social definitions/performative contexts.

Yoshito Sakuraba is a New York City-based choreographer originally from Japan. He is the artistic director of the dance company Abarukas, which he founded in 2012. His work has been performed in Germany, Poland, Italy, Spain, Israel, Mexico, and throughout the U.S. Yoshito’s choreography has won multiple awards including the International Choreographic Competition at NW Dance Project and Choreographic Shindig at Whim W’Him; the Best Choreography Award in Italy by FINI Dance; and Audience Prize at Masdanza International Contemporary Dance Festival in Spain. His work has been performed at numerous venues throughout New York City and around the world.

Artist statement

It all starts from one idea or image, and I let it grow until it doesn’t. In my process of making dance I find a way to push boundaries and create imaginative images by offering feeling, resonance or exhilaration with the work. Subsequently I build a visual storyline and weave a narrative that reverberates with ideas of love, loss, and human struggle. I value originality, style, design, approach, technique, and theatricality. Theatricality, however, is perhaps the main objective within all of my past work. To me it represents the density of signs and sensations built up on stage starting from the first lighting cue; it is the ecumenical perception of sensuous artifice—gesture, tone, distance, substance, light—which submerges the text beneath the profusion of its external language, and the belief that dancing is the most powerful way to tell a story.

Proposal excerpt

My goal during the residency is to influence and be influenced via collaboration with another artist/composer. Throughout my career as a choreographer I’ve learned a way of creating work, but during this residency I want to re-learn a new way and adopt a collaborative creative process, exploring new approaches to new work.

I think dance is easy to recognize but hard to define. From this perspective Rabbit Island will help me grow by allowing me to step outside my comfort zone and invest in my choreographic and narrative style. My goal is not to showcase conventional high-end dance, but to collaborate and offer feeling, resonance or exhilaration with a new work. Through the collaborative process I hope to find ways to push my boundaries and create imaginative, otherworldly images that will stay with the participating dancers.

Portrait of Na'ama Zisser by Mariana Kazarnovsky. MAMZER/BASTARD production photograph courtesy of the Royal Opera House / Stephen Cummiskey. Portrait of Yoshito Sakuraba by Rie Sugimoto. Abarukas Dance Company photography courtesy of Chris Nicodemo.

Our Selection Committees will soon announce the awarded residencies from the 2019–2020 Choreographer and Composer Residency and the 2019 Rabbit Island Residency open calls. It has been an extremely challenging process due to the quality of applications, and the committees have taken additional time to deliberate and discuss.

This year we received a record 303 applications. A large number of applications are exemplary and deserving of residency on the island, making us wish that Lake Superior allowed for a longer program season, and that our funding would equal the opportunities we would like to provide.

Interested in helping us support these programs and provide additional support to the residents? We have recently made a new donation page that makes it very easy to donate in a variety of ways. It only take a couple minutes, so please make your contribution today.

We are excited to announce our call for applications for the Rabbit Island Residency program and a new residency for choreographers and composers, created in collaboration with the Rozsa Center for the Performing Arts. The application deadline for both residency programs is February 15th, 2019 at 11:59 EST.

2018 Island Notes

Our 2018 season was a memorable one. Three incredible artists-in-residence each spent time in dedicated exploration of the island and their practices. The weather was generally favorable June through September, punctuated by a few intense storms that changed the landscape on the mainland. Island talks, visitations from long-time collaborators, wonderful fishing, and exhibitions and events on the mainland rounded off a successful program year.

– Our awarded residents were Alice Pedroletti, Calvin Rocchio, and Duy Hoàng. At nearly a month on average, their time in residence was some of the longest in our program’s history. That time offered an incredible amount of understanding of the island’s environment and camp life. As a result a prolific amount of research and work was created.

– Calvin and Duy’s residencies overlapped for two weeks in late August to mid September. The overwhelmingly positive feedback on having simultaneous residencies gives us some exciting ideas and possibilities for the future.

– We hosted two Island Talks this summer, boating over 20 visitors for day trips to meet the residents in person, share a meal, and participate in workshops or group explorations of the island.

– When opening up camp, several trees—including one of the white pines at the main landing—had been felled by strong storms in the autumn and winter of 2017. After a lot of labor, our firewood situation for the 2019 season looks very good.

– The resident bald eagles were healthy and active. While no new chicks were spotted this year, several yearlings and juveniles were seen visiting the nest.

– Evidence of a beaver visiting the island this spring or early summer was obvious around the perimeter of the island. Many small, shoreside aspen trees had been cut down. It is unknown if the beaver is living on the island.

– The ongoing biological study of our red-backed vole population continued. Having so few natural predators on the island has resulted in unique differences to the mainland vole groups also being studied. Interestingly, that may have changed this year with high likelihood of a weasel or ermine now being present. Sighted by Alice in late June, a scat sample was collected a few weeks later and confirmation is pending lab tests.

– Fishing was good, with the best results coming at dawn and dusk. The native lake trout of Keweenaw Bay and surrounding waters was frequently on the menu, but an occasional coho salmon also took our lures.

– Long-time island collaborator and Rabbit Island School mentor Christina Mrozik visited the island in July, helping represent our activities at the annual Farm Block Festival on the mainland. Christina will be returning as a mentor next year as we restructure Rabbit Island School to focus on opportunities for local young leaders.

– On the mainland, our inaugural exhibition of the Rabbit Island Collection was hosted by the nearby Finlandia University Gallery. The exhibition featured 13 artists and 20 exemplary works donated by former residents and collaborators. The opening was a great success and included a thoughtful artist talk by Calvin Rocchio who had just come off the island. Calvin also conducted a workshop with students at Finlandia’s International School of Art & Design.

– Our partnership with the DeVos Art Museum at Northern Michigan University in Marquette also continued. 2017 residents Jasmine Johnson and Rachel Pimm returned from London to premiere a new video installation in their exhibition THIS IS NOT THIS. They also delivered an artist talk at the university’s annual United conference and at the NMU School of Art and Design.

Endless gratitude to our residents and collaborators for helping define such a wonderful year on and off the island. Extra special thanks to those who support the program locally and from further afield. Patronage is one the most effective ways you can help us continue this work in advancing culture and conservation. Interested in being one of the next artists-in-residence? Our open call for applications for 2019 will be announced in the coming days.

A Sense of Place: Works from Rabbit Island

21 September – 19 October 2018

The inaugural exhibition of the Rabbit Island Collection with artworks donated by former resident artists and collaborators, featuring Julieta Aguinaco Beau Carey, Luce Choules, Sarah Demoen, Jack Forinash, Kelly Gregory, Miles Mattison, Josefina Muñoz, Andrew Ranville, Isabella Rose Martin, Walter van Broekhuizen, and Mary Welcome. Short films and videos on display feature the work of Eugene Birman, Scott Diel, Helsinki Chamber Choir, Ben Moon, Colin McCarthy, and Courtney Michalik and Michael Kent for The Boardman Review.

2018 resident Calvin Rocchio—who had just previously spent over one month on the island—delivered a talk and spoken word performance at the opening reception. Rabbit Island publications and featured articles are available to view in a “reading room” entrance to the exhibition. Contributions support the Rabbit Island Residency program and future Collection exhibitions, publications, and events.

The exhibition’s introduction—

Located four miles east of the Keweenaw Peninsula, Rabbit Island is a protected 91-acre wilderness that hosts artists, writers, and researchers from a wide variety of disciplines. Since its inception in 2013 the Rabbit Island Foundation Residency Program has received approximately 1,000 applications from 37 countries and has awarded 26 fully supported residencies. Additionally, nearly 60 artistic collaborations have also taken place. The program operates between June and September, championing the advancement of artistic and ecological thought. This inaugural exhibition of the Rabbit Island Collection provides a detailed portrait of the island and residency experience.

The exhibition is on display until the 19th of October, please stop by if you are in the area or will be visiting soon.

Finlandia University Gallery

Finnish American Heritage Center

435 Quincy Street

Hancock, Michigan 49930

Congratulations 2018 Residents

We are excited to announce the awarded residencies for the 2018 Rabbit Island Residency program. Duy Hoàng, Alice Pedroletti, and Calvin Rocchio will live and work on Rabbit Island during their residencies between June and September of this year.

We received 279 applications representing individuals and groups from 26 countries by the January 28th deadline of our open call. The selection committee spent the month of February reviewing applications, finally awarding residencies to the artists featured below.

The committee’s process included individual members reviewing each proposal in detail, offering notes, creating labels to help organize and categorize, and register initial votes. The committee then convened in a videoconference over two days, going through the entire list of applicants. At the end of the second day a shortlist of approximately 20 applicants was narrowed to 10 finalists. These applicants were interviewed for 30 minutes during a videoconference at the beginning of March, providing time to learn more about the artists and their proposal while also allowing applicants to ask questions. Afterwards, the committee took an additional three days to review their notes and consider the finalists. Finally, the committee members voted anonymously for their top three applicants, resulting in the awarded residency positions. It was an difficult decision for the committee, who showed great consideration and thoughtfulness during the entire process. The Rabbit Island Foundation is extremely fortunate to have such a committed group of alumni who help enrich and advance the residency program.

All 10 finalists and many of the shortlisted artists were deserving of a residency, and we thank them for their inspired and inspiring proposals. Unfortunately, due to scheduling and funding limitations, only three residency positions were awarded for the 2018 programming season.

Here we are sharing the awarded proposals in full. We do so in the interest of transparency for the residency program and selection process while also providing an insight to the quality, critical nature, and ambition of the proposals we receive. We do so fully understanding that the questions, research, and work put forward will likely change in the time for each artist before, during, and after the residency, and look forward to working with them during the evolution of their ideas.

The Rabbit Island Residency program is officially five years old, and the nearly 1000 applications we have received from our open calls during that time have expanded and simultaneously refined the foundation’s position on the intersection of art, ecology, and conservation. The committee sincerely thanks all who have offered exceptional work and a carefully considered proposals. It is an honor to be working with the following artists over the next year.

The 2018 Rabbit Island Residency Selection Committee

Beau Carey, 2015 resident

Luce Choules, 2016 resident

Lucy Engelman, 2013 collaborator

Rob Gorski, cofounder

Nicholas McElroy, 2014 resident

Josefina Muñoz, 2015 resident

Andrew Ranville, cofounder

Jessica Segall, interdisciplinary artist

Duy Hoàng is an interdisciplinary artist born in Vietnam who is currently living in New York City. He recently received an MFA from Columbia University in the summer of 2017. Hoàng has exhibited in galleries and institutions throughout New York and Massachusetts, and in Singapore, Israel, the UK, and Germany. He is currently working on upcoming projects at the Museum of Contemporary Art Vojvodina in Serbia, and Grafiformas in Colombia.

Statement and proposal:

As a Vietnamese immigrant arrived in the U.S. during adolescence years, the transitional moment triggers the necessity for intensive observation and awareness. My work focuses on the links between the mundanes and the phenomena, between the potential of growth to the inevitability of decay, and the connections/disconnections between one and their surrounding environment.

I work with natural materials such as plants and minerals as site specific specimens to question the sense of location, search for settlement, and “home”. The live materials in my research are often invasive, or non-native species, due to my fascination in their borderless journeys, adaptation to foreign conditions, and their impacts on the new environments. I make connections between these natural materials and human interventions through scientific and natural history studies. With emphasis on the necessity of attentiveness through observational methods and implications, the works are often time-based, where their appearances constantly change due to the natural process of decay.

I am concerned with our relationship to nature, its well-being to ours, and vise versa. I often return to the idea of the edible plants from my family’s garden, which constantly migrates over the years with us. The garden’s health is in direct correlation to its caretakers’, where they grow and decay with each other.

—

During the Rabbit Island Residency, I want to explore the land to observe and gain knowledge on the invasive plants on the island and their influences on the ecosystem there. I want to educate myself on the “local” species, draw connections to where they might have came from and how they might have ended up in the same location. The plants themselves have an embedded migrational and historical map in their own beings and the scale is excitingly unfathomable. The island is an organism existing on its own, separated from mainland, yet at the same time, sharing its DNA with the rest of the planet. I perceive the inherent connections between the minute details to the vast, incomprehensible scale as an incredibly profound philosophy.

Through the personal discoveries of the plants, I want to continue my research on the notion of migration and “nomadic home”. What is the meaning of “home” and how do we carry it with us? Survival techniques, scientific expeditions, and adaptations to the constant changing environment have influenced my work for quite some times. A large part of my practice has been working without a studio and using any available spaces as fieldwork for production, site specific responses, and new experimentations. I want to continue to push this way of making and exploration by fully engulfing myself in the wilderness of Rabbit Island while protecting the Leave No Trace policy.

With the opportunity of working and living undisturbed from the immediate modern society, I want to rediscover the personal relationship we have with nature and to question ways of improving our attentiveness to the surrounding environment. The interstitial space between the potential of growth and the inevitability of decay is a narrow path where I want the work to activate in. This give and take relationship will not only emphasize my interactions with the natural matters on the island, but also the land itself as an organism to our environment at large.

How do we pay attention?

To our surroundings?

To ourselves?

How do we utilize our senses?

How are we at this moment?

Moment before?

Moment after?

Moments altogether?

How are we to one another?

How are we together?

How are we alone?

How do we make decisions?

How do we change?

How do we experience?

How do we question?I want to utilize the precious space and time as an opportunity to be intimately regaining touch with nature and how we can improve our relationship with it. Outreaching my senses to the immediate surrounding, to the island itself, and to the rest of the world, I hope my work can be a contribution to the larger conversion of our butterfly effect on the natural world.

Alice Pedroletti is an Italian artist that works mainly with images and archives. She has exhibited throughout Europe and has had solo shows in the Netherlands, United States, and Italy. As artist-curator, she runs ATRII, a “living archive” hosted at the City Archive in Milan (Cittadella degli Archivi). The archive involves artists’ projects for the future, constantly in evolution until their realization. The project—also a working methodology—investigates the concept of “atrium” from a processual and theoretical point of view. The aim is to create an unusual comparison between artist, space, commission, and public, creating new opportunities and tools to enjoy contemporary art and architecture.

Statement and proposal:

I regularly question the photographic medium, especially all that comes from the action of using it. At the center of my research, I often relate sculpture and photography, with varying outcomes that are contain a matrix of both disciplines, and always concerning the complex natures of temporality and fragility in the mediums and materials.

I use literature, science or history as inspiration for my work, recreating ambiguous images, or memorials, where various objects or the idea of them, are obsessively collected in a subtraction process where I consider an unknown reality. I am interested in peculiar geographical sites, in which I can underline the psychological relationship between individuals and nature through photographic and analytic sculptures.

—

What would the world be like without time?

My interest in floating islands, seen as monuments, pre-existing architectures, and hourglasses, began several years ago with a study on the lightweight structural concrete. The lightweight structural concrete, in use since the seventies, is an insulating construction material with a low specific weight. Blocks can be easily sculpted and depending on the composition density, they can float in liquids. Once submerged in water, a second possible reality is created beneath the surface, which becomes a natural partition between this world - in constant evolution and destruction - and another that preserves what is slowly lost in this one. Water, therefore, becomes a metaphor: something that covers, protects, preserves and feeds what is destroyed. Something that gives physicality to an invisible, hypothetical and ephemeral reality.

What’s the meaning of above and beneath, then?

Is there a relationship between the two parties?

Do they have a common time?The relationship between space and time is similar to a large hourglass: a cone that in physics is also the symbol of time. It is theorized that time flows differently depending on the geographical position of the subject. In the mountains, it passes faster, slowly in the plain. In space, the time as we know it does not exist and everything float because time is uniform. Above and below the floating islands, above and below the surface of the water, will the time be different? What would the Earth be like if suddenly everything will be upside down?

Starting from these considerations I would like to measure the time on Rabbit Island, from the two more distant and vertical points of it. Below, towards the bottom of the lake and above, on the top of the highest tree. The measurement can also be hypothetical, investigated through photographs, drawings, and materials. What will be the flow of time or its sudden and hypothetical absence? The two different points are the possibility of a choice: they represent the future and the past, while the island becomes the space of the present, where to hypothesize solutions. Once you get off the ground this possibility becomes real: how much time do we really have? Could it end?

Calvin Rocchio is an interdisciplinary artist based in Emeryville, California who regularly uses design, publishing, and workshops with local communities to explore how we interact and understand the landscape. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts in New York in 2012. As an invited artist, Calvin has recently initiated events for several organizations and projects in the mountains, cities, and coastal communities on the west coast, along with cultural hubs and quarry towns on the east coast.

Statement and proposal:

My practice, through what’s accumulated practicing openly and perpetually, amounts to an ecological ontology––a way of being in the world that’s pliable / wavy / soft / permiable. With optimism and enthusiasm––through publishing, distribution, graphic design, image making, research, organization, rearticulation, and movement––spaces are cultivated for new relations to the environments that we inhabit and exist as parts of. These spaces, often fertilized and enriched through collaboration and exchanges that ignore the specificities of discipline, celebrate entanglement and vulnerability to momentums outside of any single perspective, human or non-human. Just the way the mind casts a wide net, or how books can point in a multitude of directions at once, the effort dissipates in being unavoidably entangled in the world.

—

Metaphors quickly proliferate between the practices of geology, writing, mining, and publishing. The parallels in digging up / distributing, inherent between the latter two mediums, is a good place to start in thinking more specifically how the historical courses of mining could influence a more place-oriented practice of publishing. How could John Henry Jacobs’ long collaboration with the ground of the Upper Peninsula serve as a model for research, publishing, and distribution? In the late 19th century, mining towns quickly sprang up in proximity to major projects, supporting social structures where they couldn’t have existed prior, and created a public around private endeavors. Miners were said to have “read” the land and stone, through speculation and subjective research–poking and prodding until they found something beneath the surface that they could excavate. The prized red Jacobsville Sandstone they cut from the eastern shores of the UP was distributed near and wide, mostly featured as a building material, making prominent appearances in early modernist architecture in Chicago and all over Michigan.

I would like to use this history of engagement with the ground of the UP through geology, extraction, and distribution, in initiating a temporary publishing platform that utilizes these histories and terminologies as a metaphorical model for producing (a) publication(s). Through the development of content, design, production, and distribution, using the geologic occurrences largely responsible for the active formation of the UP (such as lineation, syncline, foliation, and rift) as a point of departure for thinking about the guiding design of language and imagery on the printed page–book design as sight specific process of observation and excavation.

Ultimately this endeavor would fit into a larger constellation of research, projects and gatherings I’m conducting titled The Library of Ecstatic Ecology. The aim is to develop spaces to think both about existing and newly produced publications as ecological entities in their own right, and how to test new ecological orientations within these spaces.

How can a book add to the density of place, and when does the landscape begin to read us?

Our 2018 program is made possible with support from our donors and the National Endowment for the Arts Artist Communities Grant.

Our open call for applications for the summer 2018 season is live. The submission deadline is January 28th, 2018. Awarded residents will receive a generous honorarium and support to travel to, live on, and make work on Rabbit Island. The island is a protected wilderness located in the largest freshwater lake in the world. We are looking for ambitious artists from any discipline to place themselves and their practice in this unique environment. Residents will be featured in our annual publication and may receive additional support and opportunities for exhibiting their work. Download the residency application guide and submit your proposal at www.rabbitisland.org/art.