Trees in America via Nasa.

A frequently quoted 17th century prose states, “No man is an island entire of itself … any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind”.

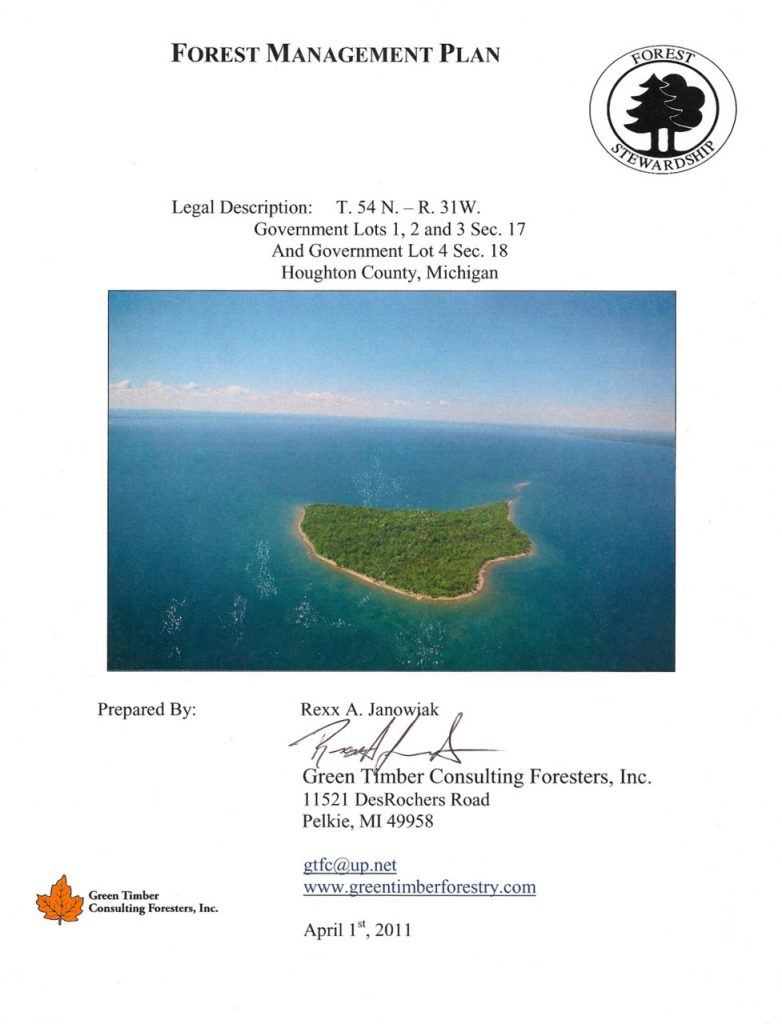

The artist residency on Rabbit Island takes a contrasting view. A view of just how insignificant mankind is. The island will continue to exist regardless of our presence and in spite of it. That is not to give the island any personification. The island is simply an island– dirt, rocks, and trees.

Immersed in the environment of Rabbit Island – its flora and fauna – I experience no mythical spirit or ethereal presence. I experience the island as the physical and finite place it is and always will be. It is a steadfast place. It fills me with awe, certainty, and respect, which obligates me to celebrate the island even more – and almost humorously – the island’s indifference to that celebration and respect reinforces my obligation.

The island’s complete and unforgiving “realness” makes it an incredibly special place to be, to create, and to experience, as long as one does not attempt to imbue it with some sort of personality. It isn’t “alive” in the same animated sense we tend to project on ostensibly beautiful or unique places; but its agelessness and steadiness contributes to a greater sense of being alive in oneself.

While “no man is an island” can certainly be true in context, experiencing Rabbit Island has led me to believe that “no island is a man” in all contexts. It is a place where a man is a man, and an island is an island. By stating that simply in five words it reinforces those understandings and elevates both to a level beyond any comparison.

Andrew Ranville’s thoughts on No Island Is A Man, a solo exhibition by the artist opening September 14th, 2012 at the DeVos Art Museum. This will be the first annual museum show devoted to artists in residence on Rabbit Island.

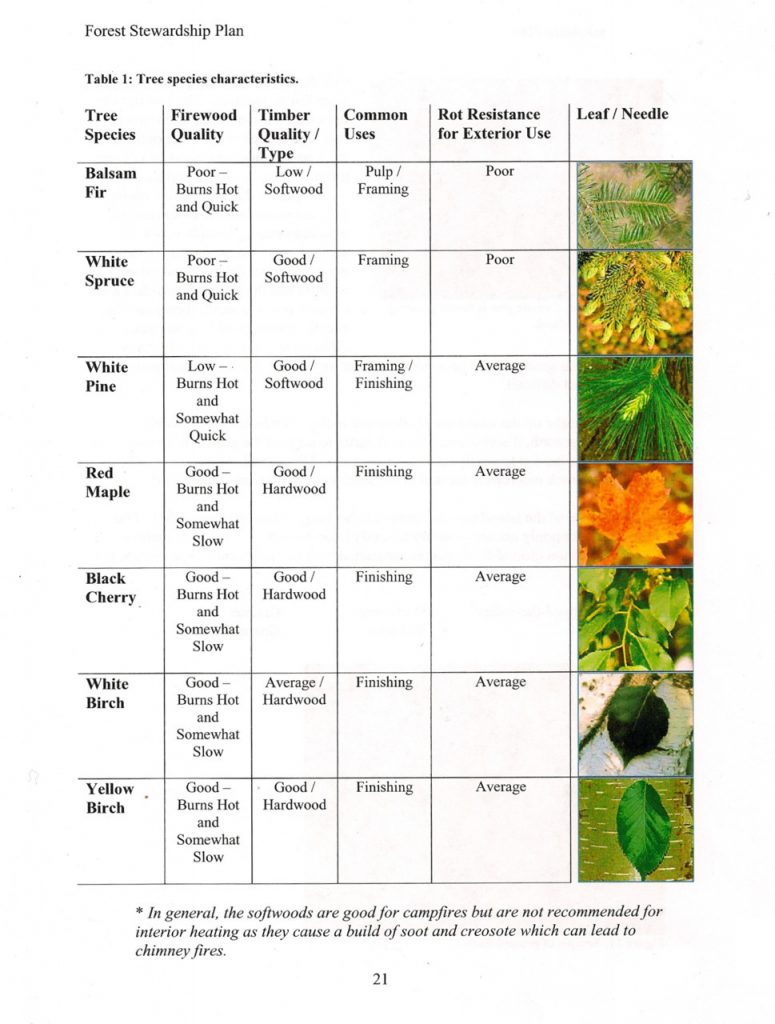

This is a rundown of timber on Rabbit Island as described by the forester who evaluated the stand. We are in the process of responding to a couple of requests from architects for specifics regarding the architecture competition; mainly a detailed topographical map and a list of wood that can be sourced locally. Note: The competition has been extended to March 31st and a budget has been formulated. Stay tuned for more.

This is the Rabbit Island Conservation Easement. Have a look.

In society land is generally purchased on an open market with two motivating premises: development and profit. Historically these ideas have manifested themselves in various forms of subdivision and parcelization. (Think of the farm that was there when you were a kid that was bought and turned into a new subdivision, or the brownstone single family house that was purchased and renovated into several one bedroom apartments, or the field that was there before the row of brownstones even existed. Consider the island of Manhattan–the ultimate example–sold to Peter Minuit in 1626 by the Lenape tribe to ultimately manifest itself as smaller and smaller subunits of private property over time). The common thread in all of these transactions of property is that the effect on the integrity of the land is never part of the bottom line. And the process rarely moves in reverse. In the end because of our society’s individual liberty and participation in a market that does not fully value the costs of development we have had the freedom to historically subdivide without the requirement of foresight. When these subdivisions are summed we see that there are significant unintended consequences: namely, there isn’t very much land left that isn’t subdivided. Collectively this limits the opportunity for anyone to enjoy intact open spaces that resemble whatsoever their historical baseline, especially near population centers. Indeed this is an odd and ironic historical loophole in the code of American ‘liberty’ and 'freedom’. (In defense of previous generations this process unfolded slowly over four hundred years and only recently became broadly visible with the help of Google Earth, etc. Both of which are interesting ideas themselves).

Subdivision is, of course, against everything that Rabbit Island stands for. Rabbit Island will never be subdivided and the miracle that Rabbit Island remained unsubdivided and unlumbered in 2010 is it’s most remarkable feature. Yet we would never have been able to get this project off the ground (read: we couldn’t have afforded to do this) without a mechanism that made it financially possible to not subdivide the land and profit from it in the traditional way. Since 2006 a program has existed on the Michigan books called Public Act 446 that assigns value to conservation of land as an alternative to development. Ultimately, this legislation was the linchpin that allowed the Rabbit Island deal to get done technically. Just before the deed was transferred from seller (an old woman) to buyer (a young man) a conservation easement was put in place which in essence donated away the vast majority of the rights of any future landowners to develop and subdivide the land. In return we received a significant decrease in the amount of property taxes owed on a yearly basis that will carry forth in perpetuity. Had this not been available the island would have probably remained on the open market and been purchased by somebody with some plan for development, likely affirming a destiny of subdividing away the eagle’s roost, the heron rookery, the virgin forest’s unique integrity, etc.

So here is the fine print of the document. Have a look. It isn’t super exciting but we wish we would have had some examples of conservation easements to review when we settled on the legal language of all 20 pages over 4 months in late 2009 and early 2010. Both then and now there was/is surprisingly little on the internet. The process was a sometimes exhausting back-and-forth negotiation between the Keweenaw Land Trust and Rob Gorski, aided by a land conservation lawyer, Ellen Fred, Esq, and a realtor, Forbes McDonald, who was patient and willing to cooperate so long as a sale went through in the end for his client. Things were at some level guided by IRS regulations fundamentaly. These discussions ultimately resulted in the legal mumbo jumbo seen here that states specifically what sort of things can be built on Rabbit Island and where (9,500 square feet maximum footprint in up to three locations… more than we ever hope to use), which trees can be cut and which can’t be (no cutting that adversely effects the function of the ecosystem), what can be mined (nothing), what can be planted (fruit and vegetable gardens, nut trees), how many docks can ever be built (two), what kind of motorized vehicles can be used on any future trails (none), what sort of billboards can be erected (none!), etc. There were more than 20 versions sent back and forth before this final copy was signed by all parties. In the end it was a political, economic, and ecologic success and we are proud to have played a role in. It is, after all, one of the project’s central founding documents. It isn’t ideal, obviously, and definitely not as much fun as some of our other projects, but it underpins every one of them.

A tip of the hat also goes to the men and women who created Michigan PA 446 and voted it into being: wise leaders with minds toward the future indeed. Our project is directly possible because of their legislation. Yet as strong as Michigan PA 446 is it is handicapped to a degree in the big picture because it only applies to transactions involving individual pieces of private property for sale in a time when individual pieces of available land are becoming smaller and smaller due to subdivision occurring with the passage of time. The next great piece of conservation legislation must move this idea forward and create a mechanism that offers incentive to combine previously subdivided land into larger contiguous units. Simply put there needs to be a systematic counterbalance to the historical direction of the private property market that aligns our collective land use culture with our modern understanding of ecology, climate, agriculture, externalities of development, etc. Maybe such legislation will get written on rabbit island.

PS. If anyone with experience in conservation easements reads this document we’d be curious to know what you think. Get in touch.

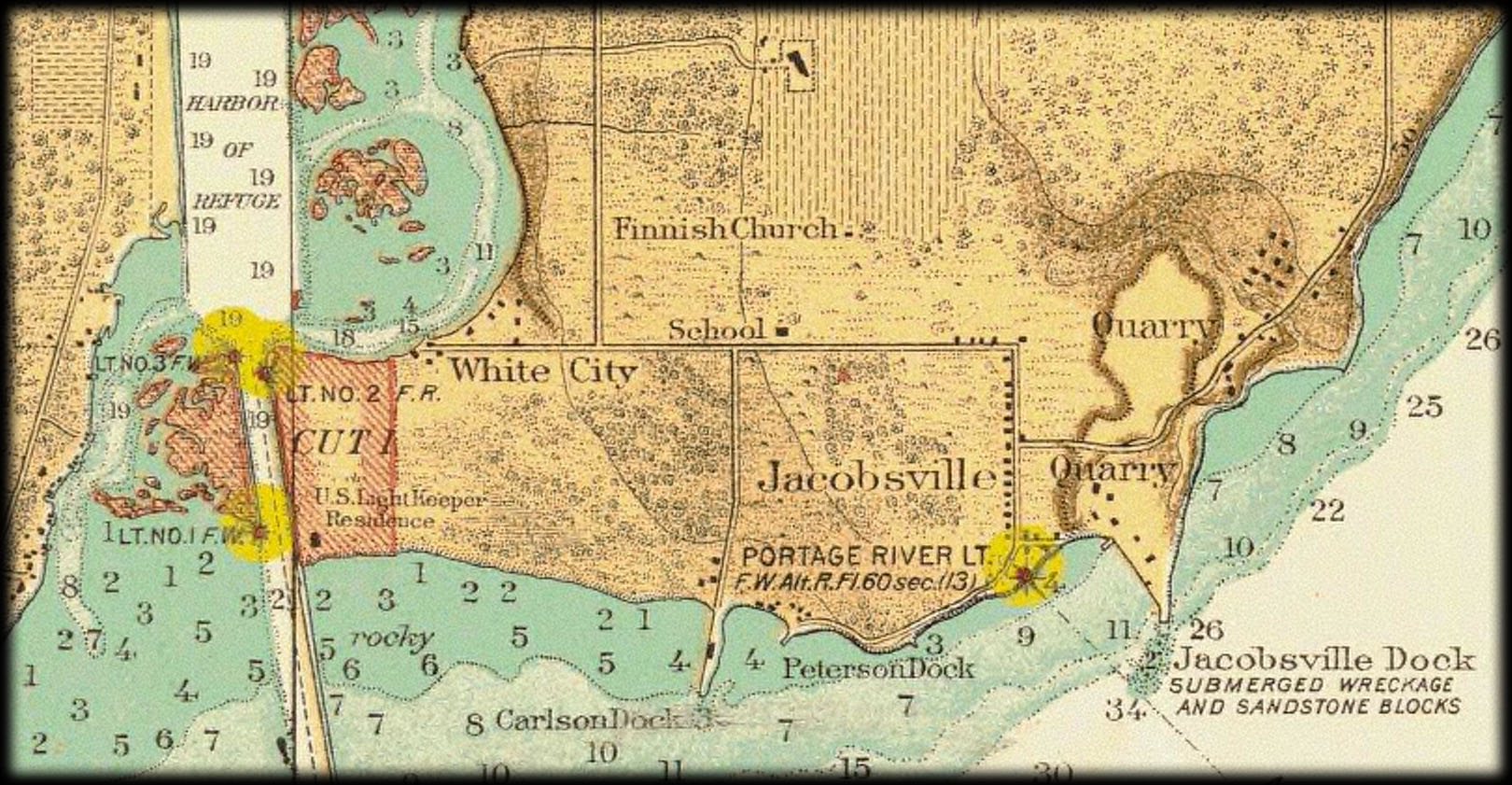

This sumer we were visited by Joshua Richardson, a geology graduate student at Michigan Tech University with expertise in Keweenaw Peninsula geology and, specifically, Jacobsville Sandstone. After making the crossing from Rabbit Bay we hiked around the island for an afternoon while he jotted down some field notes. A few weeks ago he emailed us this summary of his observations. It is fascinating. For one, the island was formed between 900 million and 1.6 billion years ago by the deposition of sand at the bottom of ancient streams, much like what can be seen in glaciated areas of Alaska today. Also, towards the bottom of his summary, he offers advice on which sandstones are the most suitable for building applications and which ones would be best for stove/sauna applications where heat and fire are factors. This info is invaluable from the perspective of attempting to not make brick-and-mortar mistakes while designing and building and will hopefully allow us to create simple structures that will stand the test of time using the best local stones available. Exciting stuff. Thanks Josh.

Dear Rob, Andrew,

I have compiled what I feel comprises a short description of the geology observed at Rabbit Island. Although I was unable to ascertain the existence of the island, there were several features that are interesting. Also, I have done some brief research to add to and correct the observations that I made based off of extensive research previously conducted on the Jacobsville Sandstone.

The Jacobsville Sandstone was deposited in the Middle Proterozoic, corresponding to an age from 1.6 billion to 900 million years before present. On the south-eastern shore of the Keweenaw, including Rabbit Island, the sandstone unit is greater than 1000 feet thick, decreasing in thickness to the southeast. While the unit as a whole is considered a sandstone, sub-units consist of siltstone (mud), conglomerate (mud with pebbles and boulders), and shale (really fine mud). On Rabbit island, siltstone and sandstone are both abundant, as characterized by solid sandstone rock (red and white), and loose, highly eroding siltstone layers (green and red to black). On Rabbit Island, some portions of the sandstone appear to have been metamorphosed (heated and pressurized, recrystallized), and turned into a quartzite, which is slightly harder than the original sandstone, but made of the same minerals as a whole. This reheating and pressurization is a result of hot fluids passing through the rock, also producing the small yet visible quartz crystals that are found throughout the island in small cracks.

The Jacobsville Sandstone on Rabbit island is made up mostly of quartz, with a minor amount of potassium-feldspar (mineral found in igneous rocks), clays, and some minor hematite (natural rust, or iron oxide mineral). The red color is caused by both the coloration of potassium feldspar and hematite. Where the sandstone is white, it is made of almost entirely quartz (SiO2), and where it is very weathered looking and soft, that is mostly clay minerals which do not hold up very well with time, and can gain and lose water from their structures.

The sandstone on Rabbit Island was probably formed by a very wide, shallow delta of large braided streams and rivers flowing into a shallow sea (like what exists in Alaska today), but may also have contributions from wave action on an ancient beach. In any case, the sandiest parts of the sandstone (white colored) on the island were probably deposited by fast flowing rivers and tidal currents, and the very fine grain (silty, dirty looking rock), by very slow or stagnant water, where the fine particles could settle out.

There are a few interesting sedimentary structures on the island, including both ripple marks and cross-bedding (or cross-lamination). The preserved ripple marks, observable near the boat access area near the main camp, as well as in other places too, are exactly the same as those seen on the bottom of the sandy beaches of Rabbit Bay, or in local sandy river bottoms, although about 1 billion years old. Ripple marks are only preserved when other sediment is quickly deposited on top of them, because the continuing river action will constantly erode and redeposit the sand. They are only found when a changing current situation happens and the energy of the water in a channel is reduced (i.e. silt is deposited on top of the ripple marks after a channel becomes partially cut off from the rest of the river and the current slows.)

The cross-bedding (cross-lamination) is found throughout the island, and consists of thin dipping layers that are not parallel to the usual bedding planes of the sandstone. Sometimes they are found with alternating red and white layers, that appear much steeper than the rest of the bedding of the island. These are useful, as the direction that these small layers or laminations are dipping tells the direction that the current was flowing when these silts and sands were deposited. These can be found all over on the island. If one were to carefully measure all of the cross-bedding directions on the island, one could ascertain the direction of the paleocurrent (literally “old current”).

In addition to sedimentary structures, the island is filled with joints of various ages. A joint simply occurs when the rock is strained to the point of breaking by regional and local stresses. Instead of faulting, where two halves of the rock move in opposite directions relative to each other, a joint simply implies a crack in the rock that opens, but where no slip occurs. On the island, the cracks (joints) in the rock that are filled with a white quartz through a generally red rock are the result of joints that were formed during the movement of hot fluids through the rock. When the joint formed due to stresses, the hot fluids with SiO2 (quartz) were quick to “heal” the crack in the rock and fill in the voids. Joints that are open cracks have been formed since the rock was cool, so they remain open and fluids with SiO2 (quartz) were not available to fill in the open spaces. Many of the joints that didn’t entirely fill up with quartz may have quartz crystals, some of which are laying around camp.

In addition to rocks formed in the Keweenaw, some rocks have been transported to the island by ice-rafting (ice sheets moving rocks and debris) from Canada. These include igneous intrusives (igneous rocks that cooled very slowly, deep within the earth, only exposed later due to weathering) like granite (pink, white, and black), gabbro (black, with many reflective larger grains), and andesite and dacite (white and black mix). There may also be some igneous extrusives too (rocks that were erupted from volcanoes like lavas, and cooled rather quickly) including rhyolite (red) and basalt lava (black, the same as the Keweenaw interior rocks).

You had also asked which rocks would make the must durable building material. Regarding this the best building stones on the island would be the white or pinkish-red sandstone. It is found all over the island, but some great samples of it are right at the boat launch. That material is hard and resistant to weathering. Avoid the softer clay units within the sandstone, since as walking around the island will show, they fall apart rather readily with the weather. The unit right by the boat launch could also be broken into nice brick shaped pieces for stacking into a structure too.

For fire/sauna rocks, the best rocks are probably the Canadian igneous rocks that wash up on the shores. Since they are few and far between, I would again pick the white or pinkish sandstone rocks that have no clay minerals (soft red,green or black). These clay based minerals have water in the structure, and will likely release the water when heated, causing violent explosions. This would be less than ideal.

I am not certain about this, but I think the abundance of rubble around the island is more of a function of currents and ice patterns than the structure of the island and strength of rocks. The larger boulders and rubble are found in areas where the waves are the fiercest, and the smaller pebbles are found where the shoreline is more sheltered, for example the one bay that we visited.

Josh Richardson

jprichar@mtu.edu