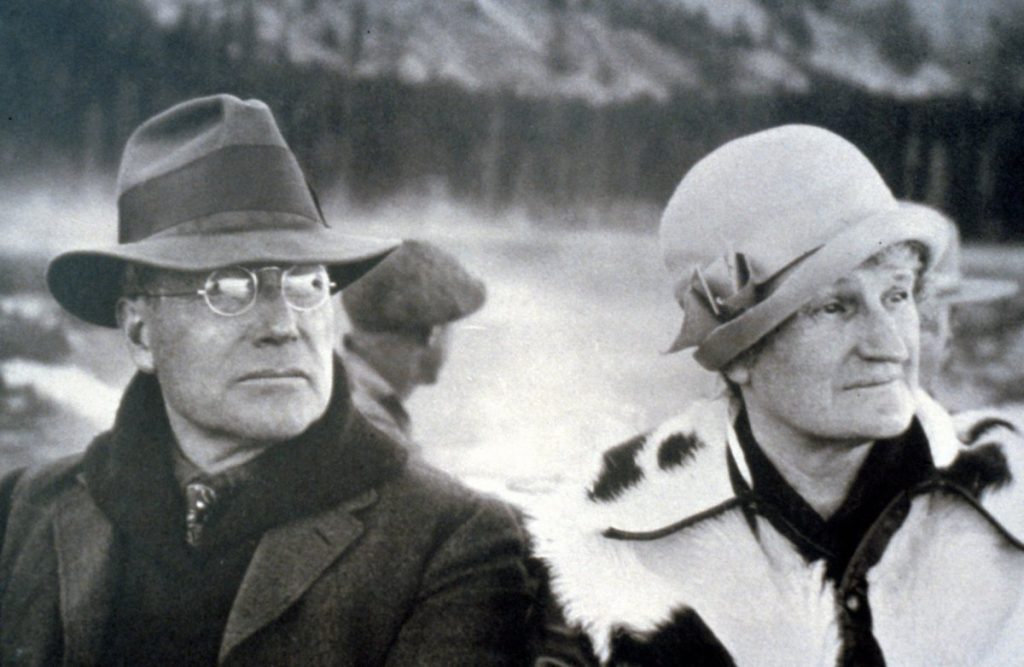

In the midst of the 2nd world war a letter arrived at the White House:

My dear Mr. President,

Many years ago I purchased some 30,000 acres in Jackson Hole Wyoming confidentially expecting that the federal government would gladly accept the land as a gift to be added to its national parks system. 15 years have passed. The government has not accepted the property. I have now determined to dispose of the property, selling it, if necessary, in the market to any satisfactory buyer.

Very sincerely,

John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

The land ultimately became the eastern half of Grand Teton National Park, an investment that has paid dividends over time. Question: Could the Kickstarter model complement the individual philanthropist as the instrument of conservation in America? The Maine Woods National Park proposal would be an interesting setting to test the waters with. If created the park would encompass 3.2 million acres and become the “Yellowstone of the East”. Not a small idea.

The Sigma K2 Hand Pump. Simple and sweet.

There is no Antonym for Subdivision

The english language does not have a fitting opposite the word subdivide, strangely. Combine, reconstitute, aggregate, multiply, unite and others come close, but none serve as antonyms in the context we use subdivision and none are closely related to economic principles underlying the way we subdivide. This nuance within our language signifies a subtle but very large cultural theme underlying almost everything else that we undertake as individuals and as a society. With the benefit of modern data aggregation and visualization it is clear that we have had many irrational blind spots in our historical land use patterns. How we arrived at the google satellite images of today from a native environment over only a few centuries is fascinating. Islands add relief to this idea by offering well-controlled exhibition within finite borders. Nantucket is a fine example of this. Land division is a complex issue that involving scales and timeframes larger and longer than the individual, and Nantucket’s historical experience to present, studied in retrospect, illustrates this complexity exceptionally well. Such history is helping inform a few "off island" conservation ideas we’ve been thinking about. (Rabbit Island itself, of course, will never be parcelized.)

In 1659 Nantucket Island welcomes it’s first European settlers after being acquired from England by Thomas Mayhew. He promptly sells shares to nine associates for “ye Sume of thirty pounds in good merchantable pay in ye Massachussetts” and “also two Beaver Hatts, one for Myselfe and one for my Wife”. The whole thus suffers its first cuts. Over the next several generations this initial event evolves slowly into the parcel maps of Nantucket and the transaction itself becomes, perhaps, an enduring metaphor for the larger American settlement experience. Purchase, profit, divide, repeat… a way of life goes on an on, though never in reverse.

Nantucket, like America, progresses through stages of discovery and frontier settlement, develops a thriving economy via the utilization of natural resources (whaling), subdivides land into parcels based on an opportunity-driven market, enters a period of relative abandonment during post-industrial collapse, and then, (finally diverging from the mainland American experience), is rediscovered as a forgotten reservoir of accidental preservation resulting from nothing more than the simple absence of human economy. In the 1980’s this historical aberrancy is recognized in contrast to the mainland development experience prompting people (successful in mainland civilization, wealthy, with strong political standing) to consciously preserve as much remaining open space as possible–a full 320 years after the process began.

This effort is undertaken for the sake of posterity, of course, even if a bit late, and is for the most part successful. Today, however, the commodification of remaining developable land around conserved open space continues and new, ever-smaller lines in the plat book continue to be drawn. This change plods along so slowly as to hardly be perceptible from within the daily routine, but lots and parcels situated near preserved land (i.e. land removed from the normal economy) are continually marketed and cut into acres, portions of acres, units, timeshares… etc. This is facilitated, not without irony, using well designed infographics created by real estate publications (as above). And when observed in aggregate the charts and graphs above imply, of course, that once the area between the red and the green declines to zero percent, the amount of property available near open space will remain unchanged for a very long time–perhaps forever–and this is what we will be left with. Final lines are being drawn. Get yours while you still can. Prices only go up. Buy now. Supply will never change. The system will never move in reverse.

We protest this idea. The fact that subdivision happened and continues to happen with such binary imbalance in winner-take-all fashion, and that land is then taken off the table, is, on the fundamental level of principle, uncivilized. As it currently stands one of two things generally happens to land within the framework of our cultural practice: 1) conservation gets to a parcel of land first and locks it in, or, 2) subdivision gets first crack and development progresses without regard for collective ideas and smaller units of land are ever-passed to successive generations. The larger picture on the map only becomes more polarized as time horizons are extrapolated further into the future. This binary historical example has obvious limitations that are in conflict with contemporary understanding. In a civilization that no longer has the luxury of new frontier it is only logical that recycling of existing land, in a manner consistent with reason and scientific advance, becomes a basic requirement for maintaining quality of life. Yet thus far in our history this has not been conceived on an organized scale. It doesn’t even appear to be part of any serious conversation. Our society’s founding documents and legal precedents were, after all, conceived in a time flush with frontier. Foresight apparently has its limits.

When the message of Nantucket’s maps are extrapolated to our entire country (an arbitrary island of larger size), it is clear that very little opportunity for parcelization and road access has been missed and open space has suffered a death by a thousand cuts, leaving only remnants of land and watersheds without disruption. When empiric numbers are studied mainland ratios of developed to undeveloped land look very different from Nantucket, and certainly not for the better. Development has most certainly won a lopsided victory over conservation in the binary historical experience. Only about 30% of American land is set aside in programs for the public intended to retain or celebrate broad stretches of natural function, and of this allotment the vast majority is unevenly distributed in western states and Alaska, and, more specifically, concentrated in areas of uneven terrain (mountains), areas containing an excess of water (everglades), areas without enough water (deserts), or regions having inclement weather patterns (far northern latitudes). If you scroll across the country (or fly from New York to LA on a plane) it becomes evident that there is not a single area of ecologically important scale that does not fall under one of these categories that has been given pardon from development.

As a result “locavorism” with respect to visiting intact natural ecosystems is not possible for the majority of the population in our country and a divide is formed whereby cultural institutions benefit primarily those proximate to urban civilization while intact wilderness areas, northern forests, southern swamps and southwestern deserts serve mainly the relatively light population density surrounding them. In very few places do the two ideas exist reasonably adjacent to one another and almost nowhere has nature been celebrated simply because it is nature without a caveat. Rabbit Island, of course, claims “cold winter” for avoiding historical development, though the fact that it was given reprieve at all at this point in history is amazing.

Empirically the evidence of land division is striking and what has been lost in most places east of the Rockies or in states without long winters is profound: anything involving systems, ideas, or populations that cross individual property lines, migrations, salmon runs, climax forest communities, apex predators, clean rivers, expansive views, dark night skies and stars, the fundamental experience of uninterrupted nature, etc. Certainly we value these things and our heritage is founded on them, yet, peculiarly, there is no organized mechanism to un-divide land hundreds of years after we started cutting it up. Why is this? This is a big question for society and perhaps–and in all seriousness–on par with the big questions of previous generations: Why were women not allowed to vote? Why were unions allowed when before there were none? Why was Medicare created? Why were African American children and White children assigned different schools? In hindsight it appears absurd that there were times when such disparities existed. So too does it seem absurd that society has no way to un-divide on an ecological scale baked in to its founding principles. There is no organized mechanism intended to give people reasonable access to the fundamental instruction that nature provides. Will the next several hundred years of American experience witness a continuation of the historical example of subdivision or will the pendulum swing in a new direction given our collective understanding that now spans from DNA to Google Earth? It seems an obvious inference to suggest that something must give. This is not to say that civilization should move in reverse or that technology should be shunned, but simply that it would be an advancement if nature and the urban environment were organized more rationally so as to maintain a more whole spectrum of experience, including the untouched, the gridded, and everything in between–on a more local level. A mechanism for this does not exist.

Below is an abstract from the journal Science on the subject of subdivision from a perspective of road building. Road building–the most physically impermeable and historically irreversible of all municipal ventures in land use–is inextricably linked to subdivision and could even serve as a synonym for ecologic subdivision in empiric terms. The authors here, protesting the status quo, define a new metric, “roadless volume”, which is a novel idea. It is easy to see the effects of roads on native ecosystems by driving around a bit, yet quantifiable data illustrating this would be useful for an organized effort to reorganize previously subdivided land based on the thesis that open spaces scaled to population centers have societal value and that this value has been under-recognized historically. Our predecessors have subdivided relentlessly and our system is set-up only to continue this. Apart from the few sparks of genius and foresight and political will that popped up along the way as we moved westward the maps above illustrate the unintended consequence of our development heritage. It is striking in aggregate.

One of our Rabbit Island “off island” projects will experiment with these ideas using new models–part Nature Conservancy, part Kickstarter, part Google Map, part B Corp, part Votizen. If you want to get involved or if you have experience with mapping, data, design, web engineering, lobbying or other relevant skills, please get in touch. Meetings will be held in New York (and on Rabbit Island on occasion), though virtual collaboration is possible from anywhere.

Contact: rob@rabbitisland.org

Science, 4 May 2007: Vol. 316 no. 5825 pp. 736-738.

Roads encroaching into undeveloped areas generally degrade ecological and watershed conditions and simultaneously provide access to natural resources, land parcels for development, and recreation. A metric of roadless space is needed for monitoring the balance between these ecological costs and societal benefits. We introduce a metric, roadless volume (RV), which is derived from the calculated distance to the nearest road. RV is useful and integrable over scales ranging from local to national. The 2.1 million cubic kilometers of RV in the conterminous United States are distributed with extreme inhomogeneity among its counties.

Art + Athletics

I feel like I have never had an imagination. Growing

up, I lived in the present, unable to escape reality with

fantasies or make-believe games. Instead I explored

the world with simple questions: constantly analyzing

and observing to the point of obsession. With a distance

that borders on solitude and physical non-interaction, I

am unattached to the realities of the every day, allowing

myself the freedom to re-organize and re-present

information.

Time on Rabbit Island in the summer of 2012 will be spent settling into an ongoing

personal obsession entitled Building the Ocean – in essence, the process of creating

and constructing a very large expanse. The expanse that I aim to represent is water:

its colours, subtle movements, forms, sounds and my own experiences within it as an avid

swimmer. Documenting the vast waterscape of Lake Superior through a collection of

photographs, drawings and written observations with a simplistically minimal approach,

I will then take these captured moments and utilize a variety of natural, man-made and

hand-made elements to assemble individual pieces. Collectively I will create, or build,

my own re-imagined ocean in both two and three dimensions.

Influencing my affinity for the water is a passion for long distance lake swimming.

As someone who has grown up jumping into lakes in the Pacific Northwest, I have

continued to swim and compete in open water events across northern California with

USMS for over eight years. In the few weeks that I will spend on Rabbit Island, I will

continue to train for an upcoming 10k swim on Lake Willoughby in Vermont. The silence

and emptiness of being on the island will allow me to prepare mentally, with a calm

relentlessness that allows distance swimmers to approach the race unemotionally, which

in the end conserves mental and physical energy. Altogether I am absolutely thrilled with

the opportunity to be in a location that allows for the experience of water both athletically

and artistically. - Sara Marcell Maynard

* Sara Marcell Maynard is a graduate of California College of the Arts in Oakland and currently lives in the Bay Area. She is a competitive open water swimmer and her proposed Art + Athletics fits nicely as we get things up and running on the island. We’re excited to have her out. She might be the only person we don’t have to take back to land by boat.

This quilt is just about spot on. Emily Fischer is a friend of friends who runs a small design studio in Brooklyn called Haptic Lab. “The Great Lakes quilt is our love letter to the Upper Midwest”. We pre-ordered one yesterday and asked for one small favor… could Rabbit Island be sewn on? She was happy to do so and it turns out she spent quite a bit of time as a kid camping on the Apostle Islands in western Lake Superior and misses the lake an awful lot. She even asked if we need a resident quilter. Of course we do!

The quilt will be great to have around camp and fits well with the ideas of simplicity, design and basic efficiency we strive for with any civilization undertaken on Rabbit Island. If you decide to get one consider having Rabbit Island sewn on and make it an extra unique keepsake. These will definitely be rarities amongst an already limited run. Other designs available at Haptic Lab are curated nicely as well and celebrate New York, Central Park, Brooklyn, Paris, Telluride, and other locales; all places that are inspiring when thinking about the intersection of the civilized world and the natural environment and how that relationship has changed over time.

Rule #1 of island life: you need a boat. The search for a functional island boat is proving to be a difficult one. Priorities include safety, reliability, longevity, fuel efficiency, and affordability. We’ve researched several models from respected boat builders (Boston Whaler, Grady White, etc.), government surplus sites selling National Park Service and Coast Guard vessels, welded aluminum fabricators in Alaska and British Columbia, and ideas from abroad (boats used in the Swedish Archipelago, for example). Our primary purpose will be moving gear and people across a large lake that can become rough at times; and we need to do this safely using the least amount of fuel for the most amount of years. Ideally the boat we’re looking for would be under 20 feet, self bailing, able to withstand scraping against rocks occasionally during loading without causing functional damage, and have a reliable, fuel-efficient engine under 115hp.

One of our favorites so far is the Stanley Islander 19 Dual Console model (above). Built in Canada near Parry Sound it is designed for Lake Huron around the rocky islands of Georgian Bay. It is self bailing (i.e. all water drains out of the boat via gravity through scuppers in the hull above the water line), fully welded aluminum (as opposed to riveted), low maintenance, tough, no-frills, and efficient… but also expensive, unfortunately. Does anyone know where we could find a used one for a reasonable price? Apparently they are very hard to come across because people hold on to them for multiple generations and there are few that have been imported from Canada. Other considerations include tested designs such as the Boston Whaler Outrage 17 or a vintage whaler model with a later model engine, Grady White Sportsman 180, or Lund Alaskan 18 or Tyee 18. These are somewhat easier to find but do not have that rare magic combination of aluminum construction and self-bailing hull (they are either one or the other). Aluminum would be easier than fiberglass to maintain and more practical while landing adjacent to a rocky shoreline should it scrape the bottom or get pulled up on shore. Pricing is also an issue. If the prices of the above models were compared the Stanley Islander is the most expensive while the Lund Alaskan is generally the cheapest. Yet the Stanley is the boat that would last the longest without diminishing function, have the broadest application, the least built-in obsolescence (and is recyclable should that time come), and would require the least maintenance–all ideals that match priorities on the island. Perhaps that makes it the wisest in the end, all things considered. If you have any other ideas post them on Facebook or send them via email to rob@rabbit-island.org.

ps. Down the road a sailboat will likely become our vessel of choice but for the moment a motorboat is needed.

This represents a basic cross-section of the slope and elevation of the sandstone that the current shelter sits upon in relation to the lake. The soil sits on solid bedrock and is mixed with occasional small and medium-sized sandstone cobble which has fractured apart from the underlying mass over the years. The bedrock ranges from being gently sloped to nearly horizontal (approximately between zero and four degrees) and roughly corresponds to the drawing at sites preferable for building. The woods surrounding the shelter extend across the island about 1/3 to ½ of a mile until the opposite shore is reached, depending on which direction one were to walk.