An interesting house on one of the other great lakes.

Rabbit Island Necker Island

Acres 91 74

Bald Eagles 4 0

Saunas 1* 0

Fresh Water 12.7% of world supply 0%

Price per night $50 $53,000

Lake Trout Yes No

Heron Rookery Yes No

White Pines Yes No

Northern Lights Yes No

U.P. Charm Yah No

“Sisu” Yes No

Accommodation Adirondack Shelter 10 Bedroom Balanese Villa

Source: Necker Island, USGS.gov, airbnb.com, business insider.

* summer 2011

Half Moon Rising – Yonder Mountain String Band

Excerpts from the opening chapters of Delirious New York by Rem Koolhass, a book dissecting the architecture built upon the wilderness of manhattan over the last 388 years as well as the systemic influences guiding the performance. The first few chapters illustrate Manhattan evolving from a native state to fully developed urban grid at a momentous pace (over the shortest period of time in the history of the world). They show that Manhattan offers remarkable–if obvious–guiding principle related to human interaction with frontier and that the settlement of the forests of Manhattan is a benchmark act of civilization. Yet it is not without mistake.

From this perspective if New York City were rediscovered today by individuals benefiting from hindsight and contemporary knowledge of environmental science, biology, historical sequence and externality, would the ensuing project unfold differently? America itself? What would a do-over look like? It is wonderful to think about.

Excerpts from Delirious New York:

“Sixteen centuries of the Christian era rolled away, and no trace of civilization was left on the spot where now stands a city renowned for commerce, intelligence and wealth. The wild children of nature, unmolested by the white man, roamed through its forests, and impelled their light canoes along its tranquil waters. But the time was near at hand when these domains of the savage were to be invaded by strangers who would lay the humble foundations of a mighty state, and scatter everywhere in their path exterminating principles which, with constantly augmenting force, would never cease to act until the whole aboriginal race should be extirpated and their memory be almost blotted out from under heaven. Civilization, originating in the east, had reached the western confines of the old world. It was now to cross the barrier that had arrested its progress, and penetrate the forest of a continent that had just appeared to the astonished gaze of the millions of Christendom.

The quotation above–from 1848–describes Manhattan’s program with disregard for the facts, but precisely identifies its intentions. Manhattan is a theater of progress.

The city becomes a mosaic of episodes, each with its own particular life span, that contest each other through the medium of the grid.

Apart from the Indians, who have always been there–Weckquaesgecks in the south, Reckgawawacks in the north, both part of the Mohican tribe–Manhattan is discovered in 1609 by Henry Hudson. Four years later, Manhattan accommodates four houses (i.e. recognizable as such to western eyes) among the Indian Huts. In 1623 30 families sail from Holland to Manhattan to plant a colony. The city is destined to be a catalogue of models and precedents: all the desirable elements that exist scattered through the Old World finally assembled in a single place.”

“Coney Island is discovered one day before Manhattan–a clitoral appendage at the mouth of New York’s natural harbor, a "strip of glistening sand, with the blue waves curling over its outer edge and the marsh creeks lazily lying at its back, tufted in summer by green sedge grass, frosted in winter by the pure white snow…” The Canarsie Indians are the original inhabitants of the peninsula.

Coney Island assumed a long sequence of names, none of which stick until it becomes famous for the unexplained density of konijnen (Dutch for “rabbits”). Coney is the logical choice for Manhattan’s resort: the nearest zone of virgin nature that can counteract the enervations of urban civilization"

“In 1883 the Brooklyn Bridge removes the last obstacle that has kept the new masses on Manhattan: on summer Sundays Coney Island’s beach becomes the most densely occupied place in the world. This invasion finally invalidates whatever remains of the original formula for Coney Island’s performance as a resort, the provision of Nature to the citizens of the artificial.

To survive as a resort–a place offering contrast–Coney Island is thus forced to mutate: it must turn itself into a total opposite of Nature, it has no choice but to counteract the artificiality of the new metropolis with its own Super-Natural. Instead of suspension of urban pressure, it offers intensification. Even the most intimate aspects of human nature are subjected to experiment on. If life in the metropolis creates loneliness and alienation, Coney Island counterattacks this with the Barrels of Love. Two horizontal cylinders–mounted in line–revolve slowly in opposite directions. At either end a small staircase leads up to an entrance. One feeds men into the machine, the other women. It is impossible to remain standing. Men and women fall on top of each other. The unrelenting rotation of the machine fabricates synthetic intimacy between people who would never otherwise have met.”

“Manhattan is a counter-Paris, and anti-London. In 1807 men are commissioned to design the model that will regulate the "final and conclusive” occupancy of Manhattan. Four years later they propose 12 avenues and 155 streets. With that simple action they describe a city of 13 x 156 = 2,028 blocks, all remaining territory and all future activity on the island. Manhattan is forever immunized against any (further) totalitarian intervention. In the single block–the largest possible area that can fall under architectural control–it develops a maximum unit of urbanistic Ego. Each architectural ideology has to be realized fully within the limitations of the block.

By 1850, the possibility that New York’s exploding population could engulf the remaining space in the Grid like a freak wave seems real. Urgent plans were made to reserve sites that are still available for parks, but “while we are discussing the subject the advancing population of the city is sweeping over them and covering them from our reach”. In 1853 danger is averted and land is acquired and surveyed for a park in a designated area between Fifth and Eighth avenues and 59th and 110th streets. Central Park is not only the major recreation facility of Manhattan but also the record of its progress: a taxidermic preservation of nature that exhibits forever the drama of culture outdistancing nature. Like the Grid, it is a colossal leap of faith; the contrast it describes–between the build and the unbuild–hardly exists at the time of its creation.“

"The time will come when New York will be built up, when all the grading and filling will be done, and the picturesquely-varied, rocky formation of the island will have been converted into formations of rows and rows of monotonous straight streets, and piles of erect buildings. There will be no suggestion left of its present varied surface, with the exception of a few acres contained in the park. Then the priceless value of the present picturesque outlines of the ground will be distinctly perceived, and its adaptability for its purpose more fully recognized.”

“The concept of a park is the architectural equivalent of an empty canvas. Theoretically it can be shaped and controlled by a single individual and is thereby invested with a thematic potential.”

What then is the highest potential of Rabbit Island?

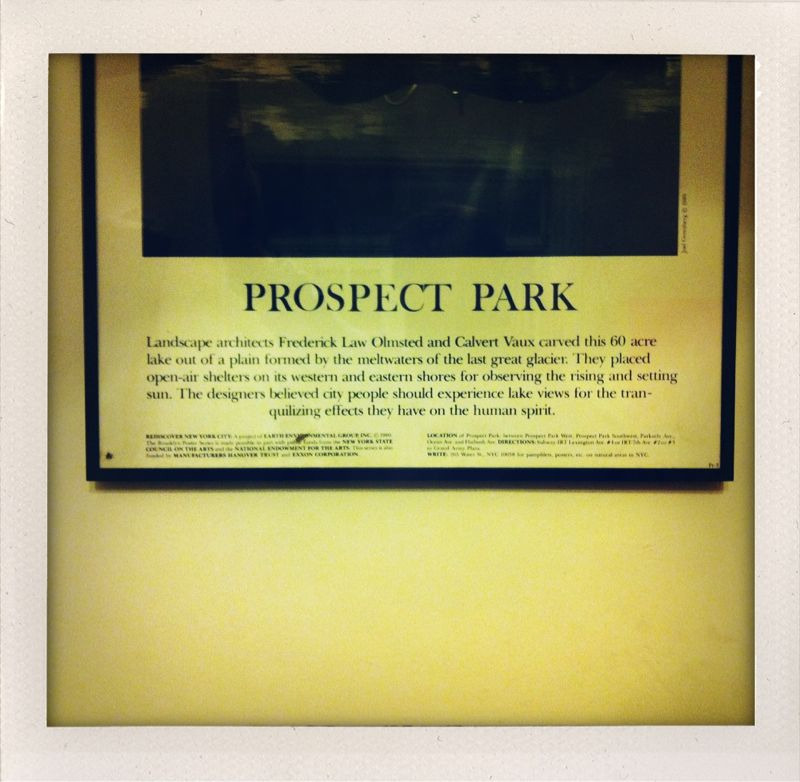

(The above photo was taken in New Orleans in 2006 in the neighborhood washed away by Hurricane Katrina. It was part of a series called the “Central Park Theory”. The remainder of the series can be found here).