Rabbit Island Architecture Competition: A collaboration of Hatchback and Northerly Design Studios

Contact:

Jono Sturt: jbsturt@gmail.com

Thomas Affeldt

Rabbit Island makes legible a curious entanglement of technology, mass and culture. The challenges associated with arriving at (let alone building on) this small, remote and uninhabited island force any would-be inhabitant to make a shift in their customary priorities.

Technology / Mass

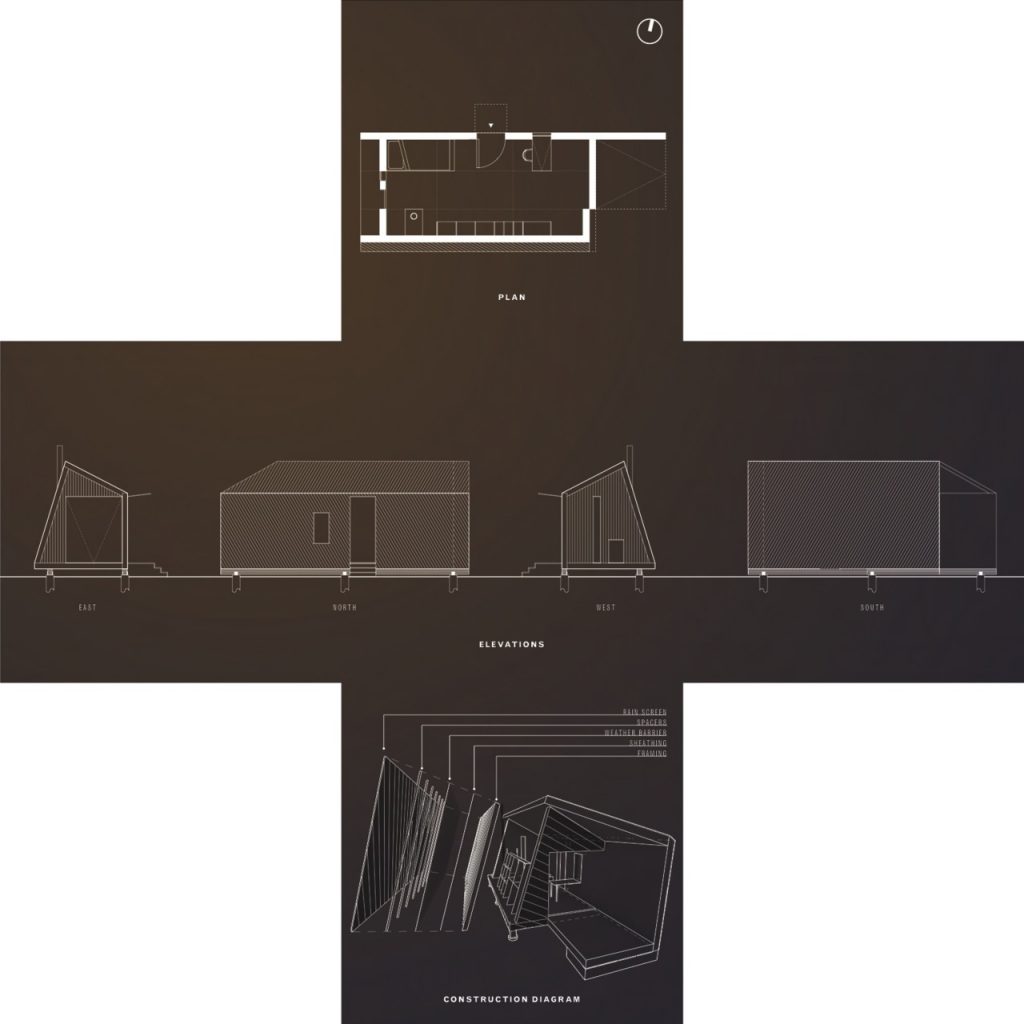

For the sake of contemporary building techniques, the absence of modern infrastructure (electricity, hardware stores, saw mills, roads, etc.) on the island effectively locates it in a separate place on the historical timeline. One cannot approach this project as if it were a contemporary suburban home; the technology that makes those buildings possible is simply not present.

Geography compounds this challenge, limiting the weight of what can be brought to the island via boat, and forces a shift in priorities, away from that of a typical project.

The metaphor of an umbilical cord– stretching from our present, all the way back to a time before places had names– seems apt here. An umbilical, only able to carry a small amount of to an unborn child, carries only what is the most valuable, nutritious, vital. So too must the building materials and practices for this site be considered; light, local, and low-tech wherever possible. To be clear, this is not an argument for a vernacular, nostalgic, or log-cabin-esque approach but rather an ambition of lightness, of flexibility, of decisions carefully made. This is not the frontier of westward American expansion, but it is a unique opportunity to address a similar context, given the advantages of a modern, globalized world.

Culture

The island’s remoteness has cultural ramifications as well as pragmatic ones. Any person or group of people spending a length of time in this place will likely come to develop a deeper, richer understanding of concepts such as solitude, presence of a place, the relationship of culture to nature… the list goes on.

To design structures responsibly for this island requires one to consider that whatever is built here will frame the occupants’ experience of being in this place.

Experience

A short summary of each proposed structure is included with its visual description. With that in mind, it seems more appropriate here to merely include certain experiences that are ambitions of our designs:

Laying the solar shower bags out on the Western rocks to be warmed by the sun over the course of a day; later, before an evening meal, a bag is hoisted with a rope to its place above the shower. The weight of the bag bends its metallic support, centering the flow of water above the light, wooden structure.

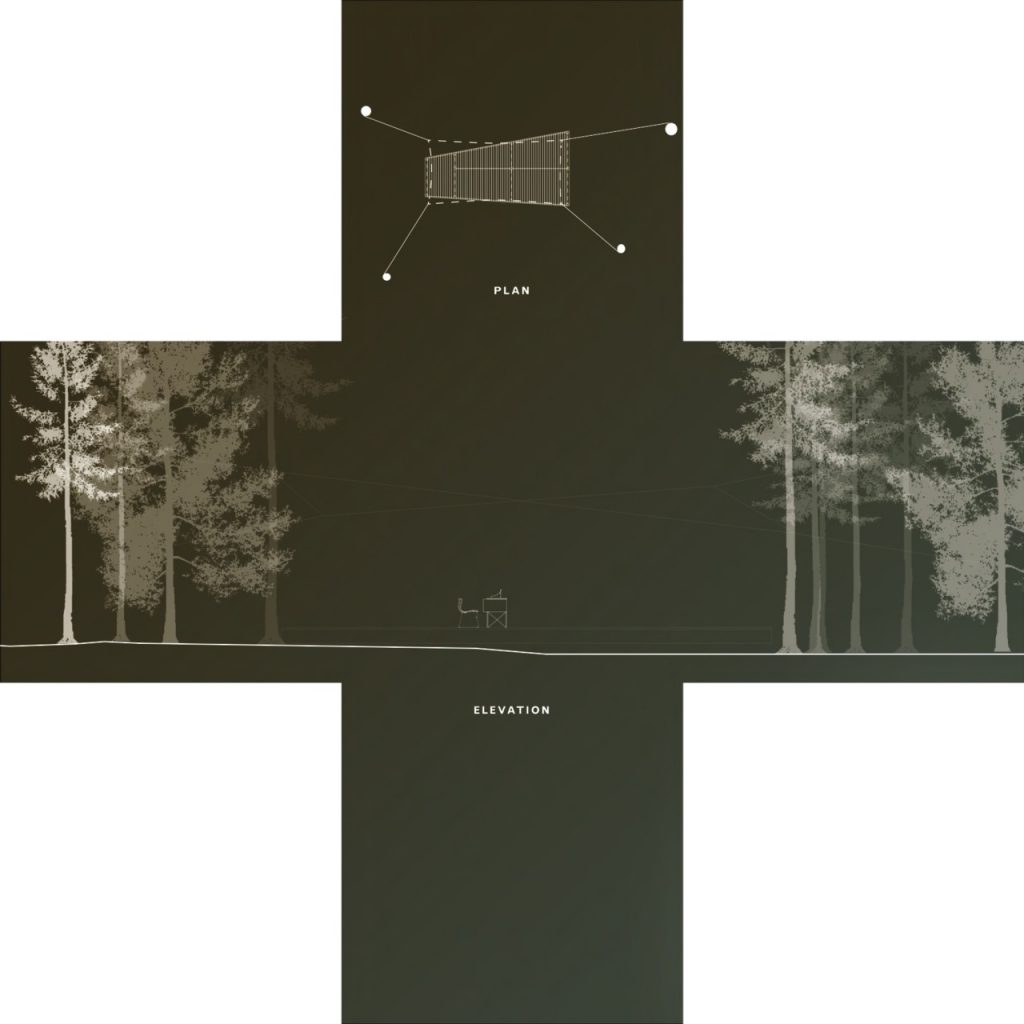

The gathering of people around a table for dinner under a canvas roof, open to the breeze, looking out over Lake Superior as the sun drops toward the water.

Painting a canvas while standing on a simple white plane, the byproduct of modernity, every glance away re-centering the painter within the natural sublime, a dense field of wood and light.

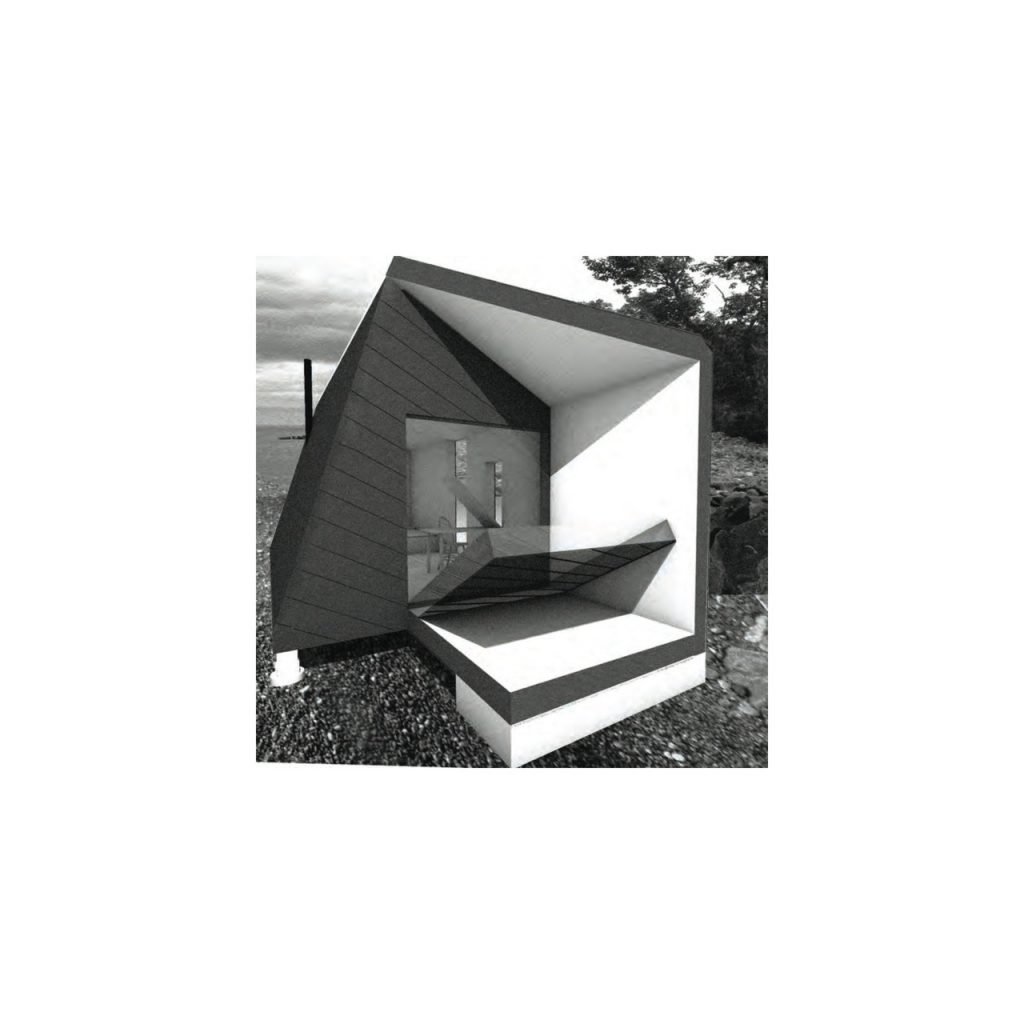

Returning through the woods to the sleeping quarters after a good day of work, ratcheting down the Eastern wall, then standing out on the surface it forms, watching the waves for a moment. In the morning, the sun floods this small room with light and color–-a vibrant but gentle alarm clock.

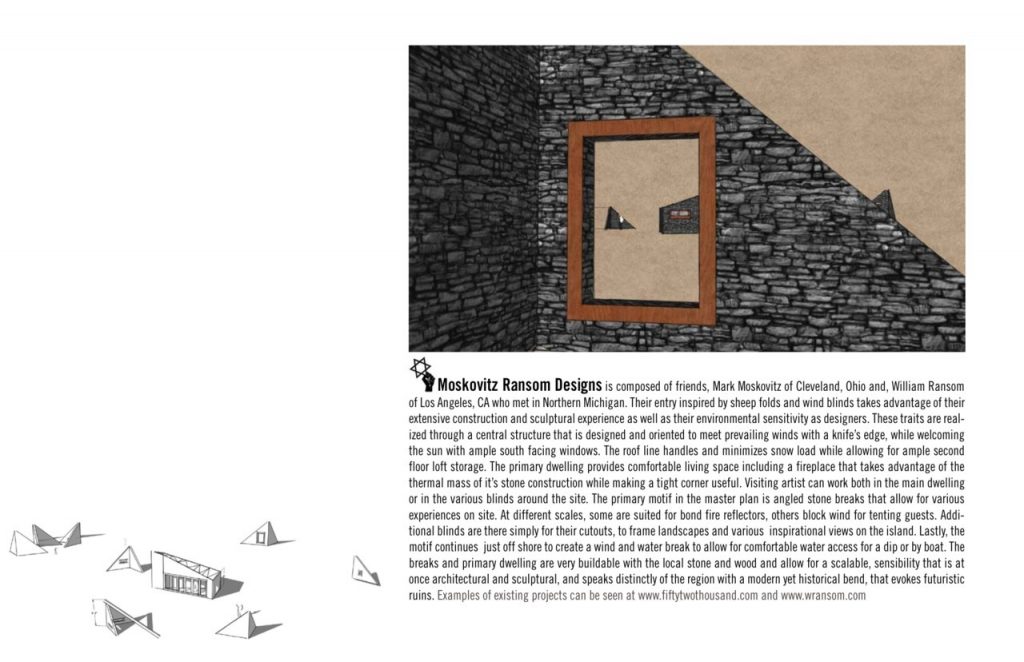

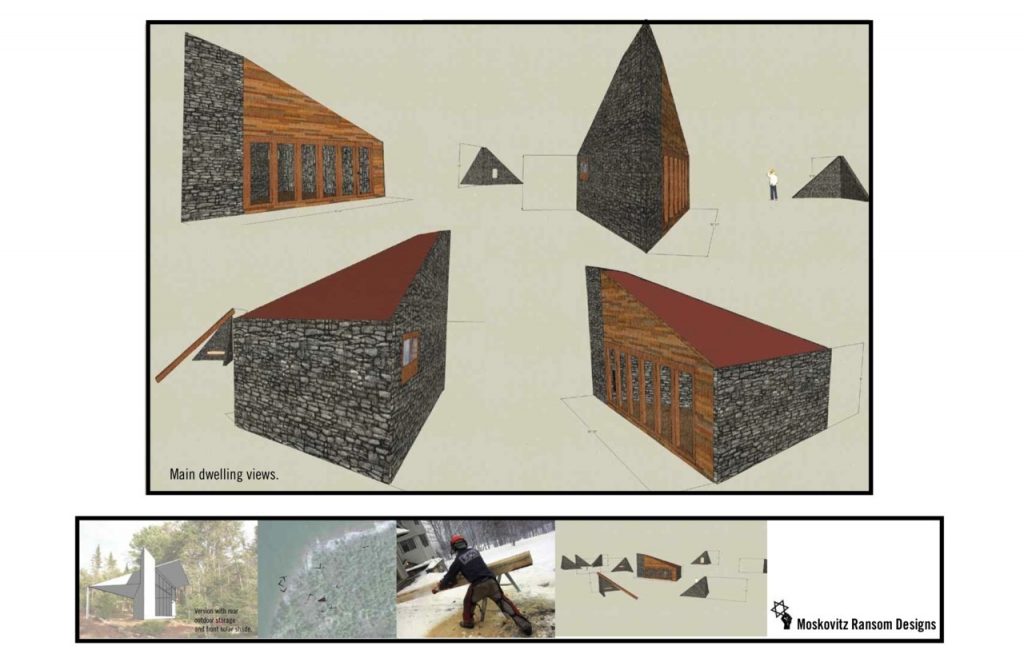

Rabbit Island Architecture Competition: Moskovitz Ransom Designs

Submission from Mark Moskovitz & William Ransom

Rabbit Island Architecture Competition: Reversible Islands. A Living Studio.

Submitted by David Soka and Fisnik Rushiti, Madison, Wisconsin.

“And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes — a fresh, green breast of the new world.” Ch. 9, The Great Gatsby

If we discovered Manhattan today as pristine wilderness, what would it look like? A small island in Lake Superior nicknamed Rabbit Island might give us the opportunity to go back in time. In Delirious New York, Rem Koolhaas describes Manhattan’s commissioner’s grid plan of 1811 as an “artificial domain planned for nonexistent clients in anticipation.“ Although the grid plan was visionary and successful beyond anyone’s wildest dreams, it could not be appropriate to overlay a grid on a virgin landscape and ignore its natural attributes today. If we are given the opportunity to build a small structure on such a magnificent island, it should begin with the notion of how we can begin to reverse the environmental damage that we have inflicted on our planet. This structure can ignite a conversation of how we should build in the 21st century and push the definition of sustainably to the next level. Initiatives such as The Living Building Challenge and The Natural Step can help guide us through this process. Much in the same way that the culinary world has embraced field to fork and locally sourced ingredients, architects are embracing critical regionalism. However, in the 21st century, ingredients can be local, but ideas are global and know no boundaries. The cathedrals in Europe and farmhouses in Japan were created by the labor of generations. The building of this structure can be a celebration of a global community of artists and artisans coming together to create something that in many ways should never be completed.

Reversible Islands, A Living Studio

Site: We propose locating the new studio just north of your existing cabin. Once the new studio nears completion, builders have the option to salvage materials from the existing cabin for the new studio.

Materiality and Concepts:

Forest to cave. Wood to stone. Impermanence to permanence.

The studio is comprised primarily of materials harvested from the island. Any materials not from the island will be sourced as locally as possible. Components of the studio are listed below, letters corresponding to the isometric diagram.

A. Porch: When the sliding screen panels are closed, they will protect the interior porch (the space between the wood screen and hay bales) from wind and create dramatic shadows, similar to a forest floor. When the panels are open, they allow the full porch to be used as outdoor event and performance space.

B. Wood screen: The screen lets the low profile structure visually dissolve into the forest much like camouflage, and protect the structure from the harsh winds. Each screen panel will be constructed from one tree from the immediate forest. The screens are supported using conventional barn hardware and can slide in any position across the facade. Found objects can be woven into the structure like a bird’s nest. Visiting artists can reconfigure the patterns of the screen for their own creations.

C. Straw hay bale construction: Hay bales are an inexpensive, easy to handle material for constructing walls with insulation values up to R-50, depending on bale thickness. Hay bale construction is an ancient practice, repopularized on the American great plains after the invention of the mechanical hay baler. Hay bales will be transported from the nearest farm to the island on a large wood raft. The voyage on the raft can be an art event, with films projected on the surface of the stack of bales (see “Hay Bale Cinema”).

D. Studio space: The studio space is 40’ x 20’. This proportion allows for maximum flexibility and frontage to Lake Superior. The southern elevation of the studio will be constructed of recycled bottles and clear broken glass, allowing light to penetrate deep into the space during the long winters. The floor will be constructed from a combination of reclaimed lumber and stones from the site. Any existing bedrock outcroppings on site should be celebrated and allowed to protrude through the floor.

The roof structure is constructed of small-membered wood trusses. Unlike heavy wood beams, these light and flexible trusses come from more readily-available logs. The longest span is 22’ and can accommodate heavy snow loads. The shallow pitch allows snow to accumulate and provide extra insulation during the long winters. Artists can suspend objects from the roof trusses. Shingles will come from native stones.

E. Open kitchen & fireplace: The indoor kitchen has ample counter space along the north wall and easy access to the main studio space and the outdoors, allowing for flexibility during large dining events. Mobile kitchen and bartending units are available for outdoor events.

F. Wood and stone shelf: Symbolic of the water’s edge and rocky contours of Lake Superior, the shelf is a repository for books, objects of personal significance, and materials from the island. The wood and stone shelf also functions as a screen or filter between the studio space and the gabion sleeping caves.

G. Stone corridor: The space between the wood and stone shelf and gabion sleeping caves. Some of gabions will extend into the corridor for seats.

H. Bathroom: The experience of bathing in a space surrounded by stone will remind one of swimming in the caves along Lake Superior. The room will hold a deep bath, shower and sauna, with a composting toilet in an adjacent separate space.

I. Gabion sleeping caves (bedrooms): These are inspired by the small caves along the edge of Lake Superior. Since concrete is responsible for 8% of global CO2 production, we feel that no concrete should be used to connect stones together. Since the island offers a large supply of stone, we propose stacking stones in inexpensive, lightweight galvanized metal cages, creating gabions. The gabions can contain stones of various sizes and colors; it’s up to the individual builder how each gabion will appear. Since hay bales will act as the thermal barrier, the gabions can be constructed over several years. Each bedroom is 8'x8’, with beds suspended from the roof structure that can fold into the walls.

J. Storage and prep: The storage space will hold an electrical generator and tools. Prep space will hold tables for cleaning fish, butchering meat, and processing other foods.

K. Vegetable garden: Rainwater will be harvested from the roof and directed into the garden. The garden sits in a protected area within low stone gabion walls and is oriented towards the southwest.

L. Entry.

M. Recycled glass walls: The southern elevation of the studio will be constructed of recycled glass that symbolizes refracted light underwater. Recycled stacked glass, wine bottles, and clear broken glass reduces CO2 output of construction and embraces the imperfections of glass from old buildings and automobiles. The wine bottles that float to the island or enjoyed there can be added to the wall. To conserve energy, we recommended that no more than a quarter of the walls in the building are glass. Most will be on the south and west facades, to harvest sunlight.

David C. Soka, Architect: dsoka@flad.com

If he could, architect David Soka would live off of stones, woods, water and art alone. His favorite memories of growing up in the Hudson Valley are stacking stone walls with his father and working with his mother in her vegetable garden. As an undergrad at the University of Kentucky and an adjunct assistant professor at Ohio State University, David embraced the undulating landscape and farms of the lower Ohio valley. After completing a Masters of Architecture at Columbia University, David spent a year in Kyoto, Japan on a Keimeisha Fellowship. There, he studied traditional Japanese carpentry, painted watercolors of Zen gardens, collected grass for the roofs to be woven into the Kayabuki Minka, and developed a serious love of Japanese baths. David lived and worked in New York City for the following ten years at Edward Larrabee Barnes/ Lee Timchula Architects. In New York, he met artist Maureen Connor, and collaborated on an installation for Barcelona’s Antoni Tapies Foundation. David moved to Madison, Wisconsin in 2005, where he now designs sustainable university research buildings as a licensed architect and a LEED Accredited Professional at Flad Architects. David draws sustenance from rolling farmland, freshwater seas, and barn rafters of the Great Lakes, inspired by the environmental legacies of John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and Gaylord Nelson.

Fisnik Rushiti, Architect: fisnikrushi@gmail.com

The 21st century will force mankind into rethinking how we can inhabit nature without destroying it.

The elements that have defined the envelope of a building for thousands of years, the floor, walls and roof, continue to challenge architects. The act of building is about creating environmental, visual and emotional relationships between inside and outside. The urgency to conserve energy and create structures with minimal environmental impact moves all of us to be more innovative.

Fisnik Rushiti is passionate about these issues. After studying at The Technical University of Vienna under Finnish architect Kari Jormakka, he traveled extensively in Europe, drawing from naïve traditional architecture like many modernist architects of the 20th century. He has visited numerous villages and cities of western and eastern Europe, including Manarola, Positano, and Portofino in Italy and Dydima (Didim) and Kemer in Turkey.

For the past 15 years, Fisnik lived and worked in Madison, Wisconsin. At Flad Architects, Fisnik merges energy modeling and architecture, science and art, to help enhance the environment and human potential.

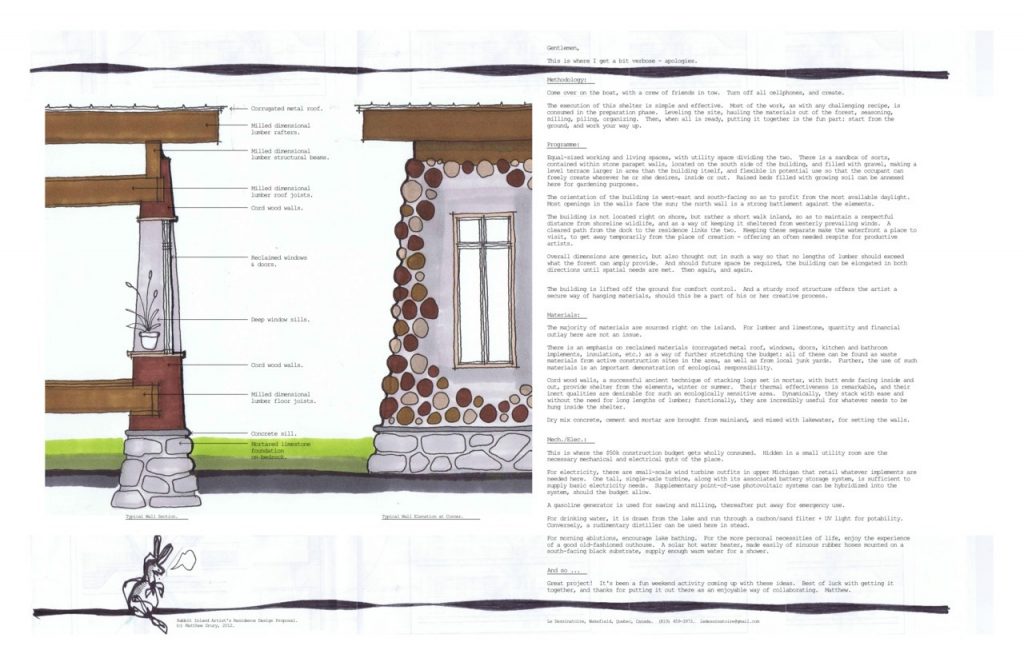

Rabbit Island Architecture Competition: Matthew Drury

Contact: ledessinatoire@gmail.com

NOAA Satelite Images: Real time images of Lake Superior updated every 6 hours provided by the NASA MODIS program. It is interesting to watch the region transition from winter to spring in slow motion. Many thanks to Marlin Ledin of the Small Boat Voyageur project for sending this link along. Martin is about to set sail across Lake Superior for 5 months of exploration and sound/video work on his twenty-four foot sailboat. We'll be crossing paths in late July or early August on Rabbit Island. Godspeed buddy.

Call For Recipes: the Rabbit Island Cookbook

Three miles of open water, two local farms, one Coleman stove, a campfire, a dutch oven and a set of stainless cookware definitely up the ante when thinking about how to eat intelligently. We’re making a cookbook–part grocery list, part menu, part primer–but here’s the thing: we’re not cooks. Help!

The book will be designed in NYC and put together at the self publishing department of McNally Jackson. Ingredients for recipes will be gathered on the island and from the nearby Keweenaw Peninsula: Produce will be purchased from the Hughes Farm in Calumet and Chip Ransom’s Farm in Houghton; dry goods and staples will come from the Keweenaw Co-op; berries will be gathered on the island shores; trout and salmon will be caught in the lake, Gods be willing (they usually are). These are our limitations and we’re excited to experiment with them and come up with a simple but interesting menu.

For recipe ideas we’re starting with available local ingredients and cooking methods and working backwards. The book will be divided into three sections correlating to daily life on the island: breakfast, lunch and dinner.

We’ve asked some friends for recipes and advice and so far Noah at American Spoon, T.J. from Pinch Food Design, Kelly Geary of Sweet Deliverance, Seema of Simply Seema and Patricia Hughes of the Hughes Farm have voiced interest. We’ll also be including local plates such as lake trout with thimbleberry glaze, one of Scott H.’s creations (our neighbor in Rabbit Bay) and hopefully a variation of the traditional U.P. pasty.

But we could still use some more ideas. If you’re interested in submitting a recipe for the project we’ll publish it and also photograph it being prepared this summer to be included in future editions. Recipes can be anything you like–a dutch oven stew, a simple vegetable dish, a berry preserve, a drink, etc.–so long as it can be created within the limitations we face as noted below. Get in touch with any questions or other ideas and include the title of your recipe, the ingredients (to be chosen loosely from the list below), and the instructions for preparation. It doesn’t have to be anything fancy, though it does need to fit on one page. Less packaging is always better than more. Less stove time is better than more.

We’re also looking for a Rabbit Island Resident Chef for the end of July and early August. You’d be put in charge of everything food and would help plan a garden, curate kitchen supplies and organization, direct the building of a wood-fired stone oven for baking, and whatever else you were interested in undertaking. It will be an adventure. If you can’t make it out but have knowledge to share we’d love to hear it as well. Just get in touch!

Submissions: rob@rabbitisland.org

Ingredients Available:

Vegetables (See farm websites below for availability)

Pantry Staples (rice, grains, flour, sugar, barley, oils etc.)

Thimbleberries, Wild Raspberries, Wild Blueberries, Choke Cherries

Rabbit

Cooking Methods:

Dutch Oven

Wood Fired Stone Oven (future project)

Food Sources:

Hughes Farm in Calumet

Chip & Cindy Ransom’s Farm in Houghton

Keweenaw Food Co-op (a typical variety of coop goods available)

Refrigeration:

Cooler

55 degree fridge (i.e. Lake Superior)

Reference:

The Pleasures of Eating, by Wendell Berry

Ron Gorchov

Ron Gorchov is a friend and mentor and his distinctive saddle shaped paintings have become iconic to us, symbolizing, in many ways, ideas we wish to draw from on Rabbit Island. His work has received much art world acclaim–several links to reviews and discussions are below–though what we like most about it is relatively basic: he produces beautiful and relevant art using simple means that have little externality.

We have been working on developing a set of “Island Rules”, a la the Food Rules, to explore conceptual lifestyle relationships that can stand in conflict with one another; creativity and waste, entertainment and excess, building and ruin, art and consumption, travel and energy, health and cost, etc. While this effort is very much a work in progress Ron’s paintings have inspired us with themes that will inform the list. Simplicity, relationship to form, and restraint will always be relevant across the board.

Form is the fundamental point of reference. We interpret the negative space around the two iconic shapes on Ron's canvases to suggest the human form in various poses or actions–the torso centrally and the upper limbs wrapping around above. While many concepts are subjective–entertainment, law, happiness, art–the form itself is a constant and a direct extension of the primitive. This is important to recognize. When one strays far from this measuring stick there is ever-increasing potential to impart significant unintended consequence on things around you.

Beauty is subjective and excess cannot increase it. Ron’s work does not need to be plugged-in, projected, or critical of the past or present in order to be relevant. It is as basic as the materials it is created from–which are only a few degrees from their source–yet it represents volumes with the way it is organized. When artists remove themselves from such simplicity and when their concepts and creations become a burden on society in absolute physical terms, things run afoul and generally in the wrong direction. More is not always better.

Change is not more appealing than consistency. The act of changing; renovating, updating, diversifying, traveling, etc., implies an associated act of consumption and/or externality. Ron’s consistence, in this sense, both in terms of practice as well as location, might be likened to concepts of notable permanence–a stone house not diminished by generations, a well-conceived stainless steel object resisting tarnish, an heirloom. Ron’s work will not likely go out of style, will never diminish the opportunity of another, and will never require remediation. It will fade in time but will not require active deconstruction.

Born in 1930 Ron has been making shaped canvases in New York since the 1960’s. His recent work is being shown until April 28th in New York at 547 W. 25th Street between 10th and 11th. This show has certainly influenced Rabbit Island.