State of the Union: A Listener’s Guide

What is New Music? And why should you care?

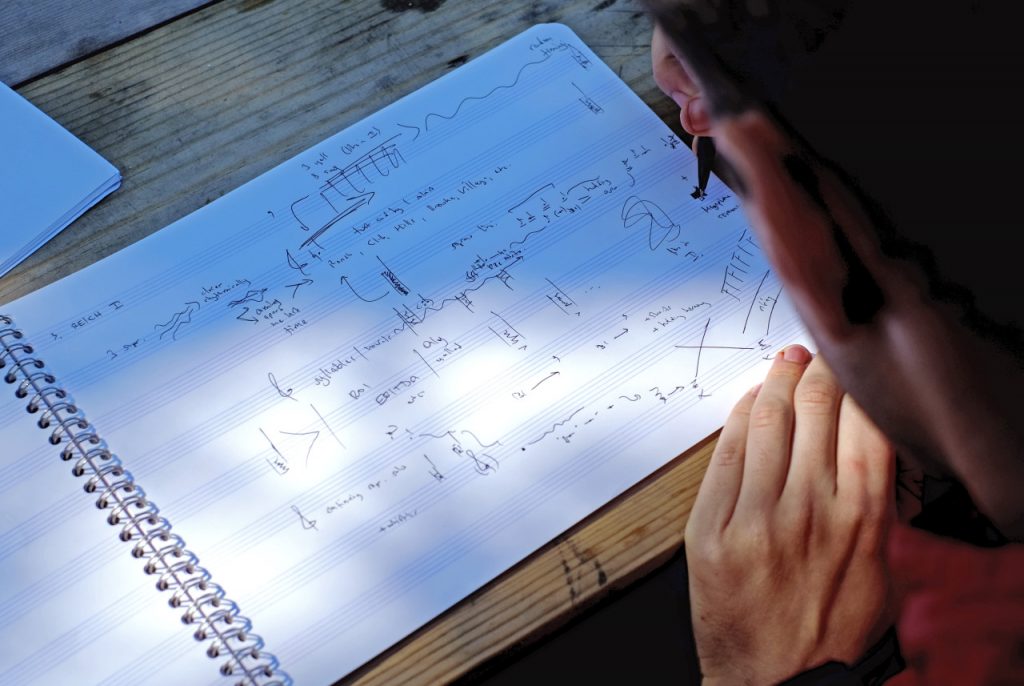

Attending a new music rehearsal of a work not our own, composer Eugene Birman and I quietly passed notes on an appropriate title for the piece:

“Sounds kids are not allowed to make at the table”

“Object dropped from great height”

“Rattlesnakes”

“Indian war whoops”

“Use this time to pay your bills”

Having reached the conclusion that the work left us with nothing, we exited the hall and entered the elevator, where we were serenaded by “Spring” from Vivaldi’s Seasons.

“Of course this was new once,” remarked Eugene. But it was hard to imagine that “Spring” ever caused people to flee a concert hall or could possibly be conceived of as outside the canon.

But attempt to listen to it (first movement, allegro) with an open mind and you might come up with titles like “Prematurely elated newlywed bride” or “Floor five; going down.” Try to listen, being open to the possibility that the piece has qualities that could conceivably make a person want to run through the orchestra smashing violins with a baseball bat.

So why exactly do we like Seasons? Is it because we’ve been told it’s great so many times that who are we to argue? And who (other than Martin Bernheimer) really goes to a performance actively looking for things to dislike?

As members of a modern society, whether we recognize it or not, we are programmed to feel certain ways when we hear certain music. Music with a purpose. Or perhaps music that has found a purpose.

Take the “Ride of the Valkyries.” Listening to this, who among us couldn’t enjoy a conversation with those of another ideology while hovering overhead with a M60 machine gun? (“Outstanding, Red Team, outstanding. Getcha a case of beer for that.”)

Or consider the Tristan Chord heard in the opening phrase of Richard Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde. Even non opera fans know it from movie scenes where someone’s drink gets poisoned.

Or, departing from Wagner, there’s Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana (“O Fortuna”), perhaps the most used mood setter for cataclysmic events.

Grace Slick recently remarked on “White Rabbit” in the Wall Street Journal: “Minor chords have a certain darkness and sadness… I shifted to major chords for a release and to celebrate Alice’s courage…” No secret there, generally speaking. It’s just that we non-music people don’t really think about it that much. But there are composers who do. New music composers like Eugene.

“Why should I be attempting to do what so many dead white guys have already successfully done?” I’ve heard him ask.

New music composers find greater challenge in abandoning the the conventions and attempting to create new musical triggers.

“With SOTU,” says Eugene, “it’s the idea that, from the first moment, the music must put you in this new, undiscovered world and then you lose your free will and are at the mercy of the composer and librettist. At least, ideally.”

So new music is an attempt to create something that we, as listeners, can react genuinely to, a virgin experience, or close to it. Part of the fun of new music is that you don’t know how it’s going to make you feel until after you’ve had the experience.

Some say new music is about being challenged. “Because you have to think and feel,” as Heta points out in her video. It’s music that goes beyond your programming.

You may not like it all, of course. I have heard composers say that most new music is created to be performed once. Most of it will vanish before it is even recorded (not SOTU, as fate would have it). Some of it may be rediscovered in a couple hundred years.

And of course Eugene and I certainly aren’t the first to have passed notes about music we weren’t fond of. This note was passed from John Ruskin to John Brown in 1881:

“…upsetting of a bag of nails, with here and there also a dropped hammer.”

Ruskin was commenting on Beethoven. Roughly a couple hundred years ago.

Scott Diel is the librettist for “State of the Union”