Beau Carey, Rabbit Island

Opening, Friday, September 16th, 5 - 8pm

Goodwin Fine Art

Denver, Colorado

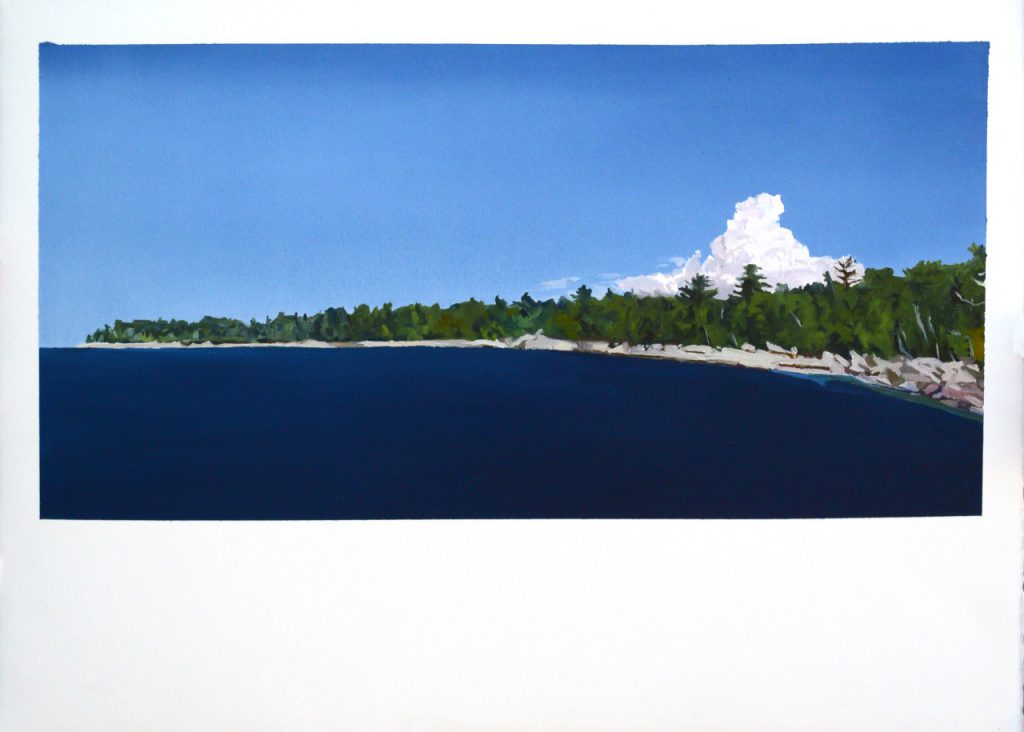

In the summer of 2015 I spent 3 weeks as a resident artist on Rabbit Island, a 91 acre island in the Lake Superior. During the bulk of that time I was the island’s only human inhabitant. I had planned to continue research on coastal profiling and it’s effects on the construction of landscape paintings. However, extended periods of solitude can erode even the best laid plans. As is often the case the primacy of experience overwhelms the mutability of preconceived notions. From the shore, from the trees and from a tiny raft I was able to make a dozen or so oil paintings. These works and the starts of ideas in them became the subject of the following years studio canvases.

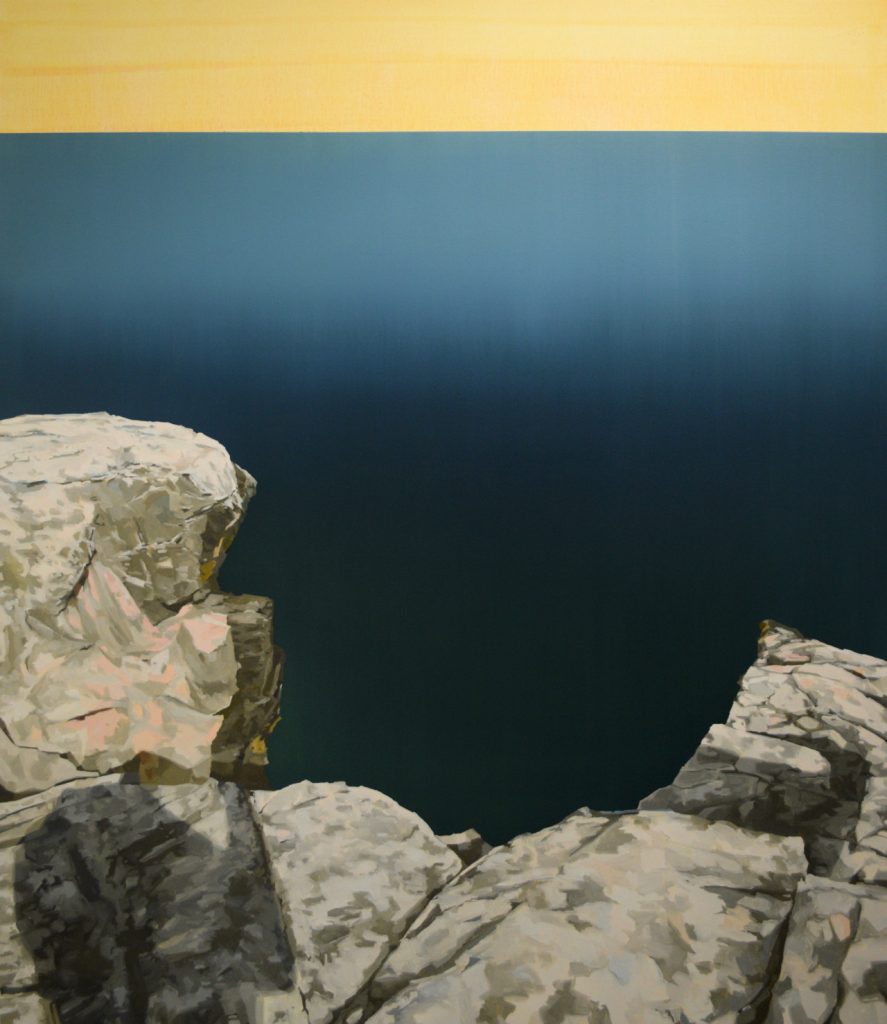

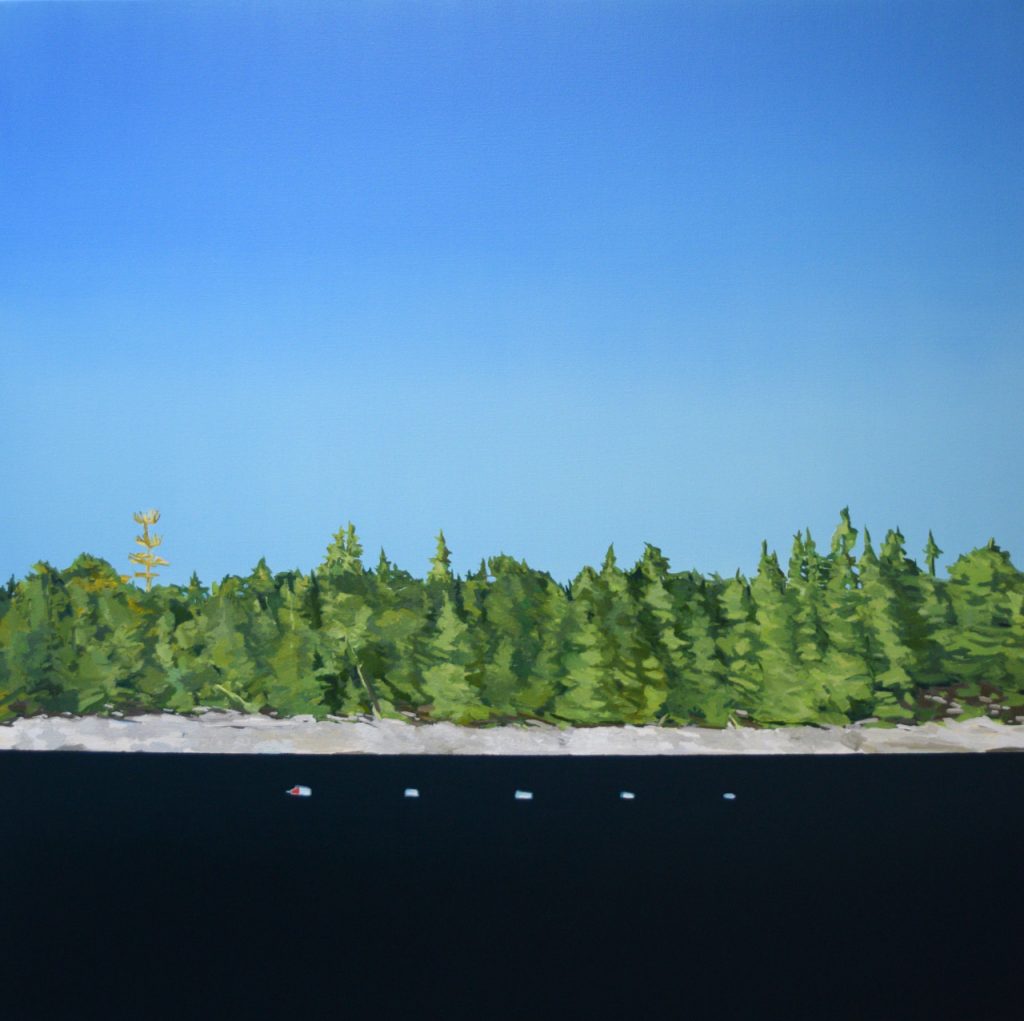

Lake Superior feels immensely deep. It also, depending on the weather and the craft you have to navigate it, feels like an insurmountable barrier. In the cliff paintings I raised the horizon line and eliminated surface detail to create a kind of wall/void. Rabbit Island doesn’t have the huge rocky cliffs seen in many of the studio paintings. The island is rocky, but I took certain liberties with scale and surface that better fit with the psychological and philosophical ideas experienced. Standing on those cliffs one is staring into an impenetrable abyss. Other works look at that tiny space between shore and open water by subtly examining views from each position. In them I was reminded of a favorite quote from the 1975 movie Jaws, “It’s only a island if you look at it from the water”. They are reminders that our labels for things are dependent on our vantage points. Together all these works synthesize my experience on Rabbit Island.

Beau Carey, 2016

__________________________________________

July 14th, 2015

9th Full day on the Island

North winds 15 to 25 knots diminishing to 10 to 20 knots by mid-afternoon. Areas of fog this morning. Waves 3 to 5 feet subsiding to 1 to 3 feet.

…Rabbit Island doesn’t need to be mapped, it’s been mapped enough. Any attempt to do so is to see it in parts.

The map is key to sub-division. To see this from that. I own this; you own that.

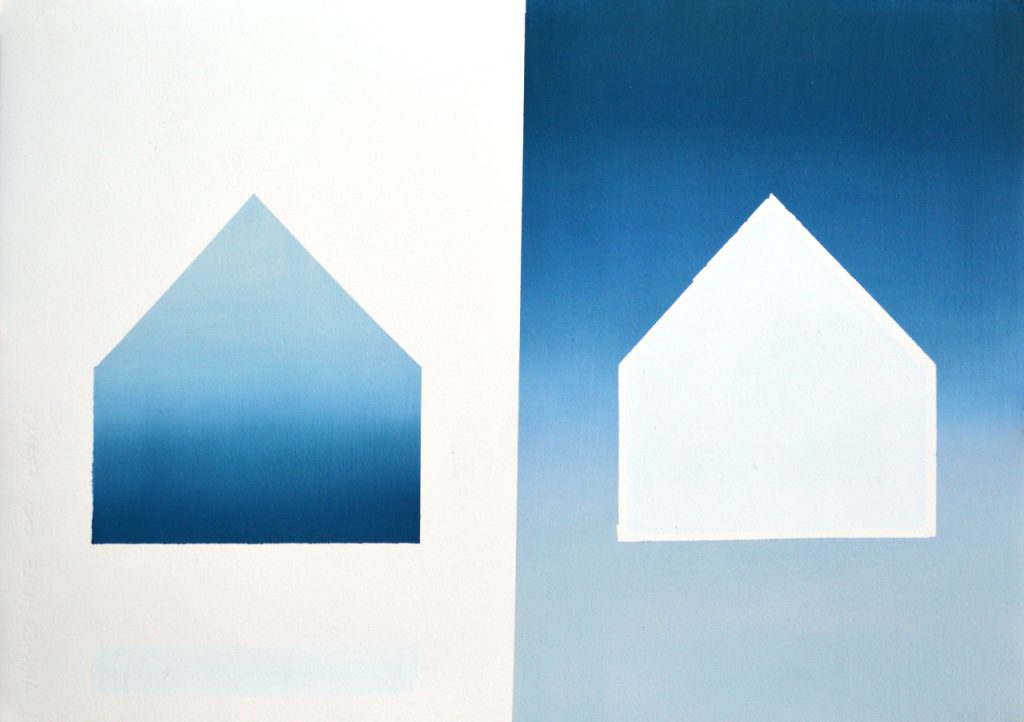

So what then? How to leave it whole yet comprehensible? In the words of Hakim Bey how do we make the island ‘invisible to the cartography of control’? To remove Rabbit Island from the process of mindless sub-division is in a very real way an attempt to remove it from the map, not as Terra Incognita (Unknown Territory) but as Terra Invisibilis (Invisible Territory)? How do we un-see something? Or how do we leave enough of the right parts to stitch together the right whole?

The above might be impossible or nonsense, the loose, unorganized sketchbook thoughts of an isolated artist on a remote 91-acre island in Lake Superior. As a landscape painter my very task is to divide and omit. I paint this and not that. I condense or expand details according the whims of the genre. I cram the world into neat little squares and rectangles of foreground, middle ground and background. I divide and sub-divide the visual into comprehensible organized space. It is folly to believe that any landscape painter paints the world as it actually is. The history of modern western landscape painting itself is rooted in imperial ambitions and environmental dominance (1), a language of division and sub-division. Rabbit Island is a chance to paint a space that envisions itself as different. The resulting work strives to say something new with old words, knowing the limits of knowledge are the limits of the language. The hope is that the encounter creates a new visual vocabulary.

What emerged was the abandonment of the rectangle as an acceptable format to start a composition. The ‘tondo’ or circular painting, largely a Renaissance tool, was used to leave those right-angled edges behind. Perception is anything but square and with the ubiquity of cameras our vision and experiences are increasingly being squared off, life as an instagram feed, an endless scroll of square memories. So two days into my stay I was tracing the main camps largest frying pan making most of my rectangular paper into circles. The X’s are both a form of division, a measurement, a survey, a reference to what I’m trying to avoid in the square, and they are a negation, a literal crossing out of the painted view. Some of the X’s are exposed under-painting, flat spaces beneath the painted surface that subvert the illusion of deep space that defines the landscape genre. And finally to paint coastal profiles from a boat even in calm glassy water is an exercise in futility. Traditionally profiles were used in navigation requiring a type of preciseness that a moving boat in my experience makes nearly impossible. It was with this revelation in mind that the July 14th sketchbook entry was written. The idea that Rabbit Island doesn’t need to be mapped and profiled at least not in the way it has been done in the past. Those tools lead us to a sub-divided world of haphazard development. What is required is the long project of developing new ways of seeing, of talking about spaces. What is required is more Terra Invisbilis.

Beau Carey, 2015

(1) Landscape and Power, ed. W.J.T. Mitchell