Congratulations 2016 Rabbit Island Residents

We are pleased to announce 2016 awarded residencies on Rabbit Island. This year the program received 177 proposals from 31 countries. The deadline for applications passed on August 29th and over the following six weeks the selection committee spent hours researching each proposal in depth and ultimately selected 16 applications to be shortlisted. The three-person committee viewed all submitted web links, references and work samples, and frequently researched artists via other online archival and social resources. Significant weight was placed on the quality of each artist’s previous work, strength of application concept, a proposal’s relationship to both the Rabbit Island program and wider contemporary issues, and the artist’s ability to demonstrate competence in the wilderness environment. Each of the shortlisted proposals was then scheduled for a 30 minute video conference. At this stage in the selection process we also queried previously awarded Rabbit Island Residents and invited them to offer feedback based upon their experiences living and working on the island. While many of the finalists we interviewed were deserving of a residence on the island, limitations related to our organization’s funding, the brief summer season on Lake Superior, and concerns intrinsic to the ecological integrity of the island’s wilderness environment–our primary concern–the committee made the challenging decision to accept four proposals for residency, including six artists in total. These artists will each receive several weeks of solitude on the island, an unrestricted honoraria to use for travel and material expenses, access to our network of mainland resources, and publication or exhibition with the DeVos Art Museum and Rabbit Island Foundation in 2017.

Thank you to every applicant who created thoughtful and inspiring proposals, and congratulations to the following artists. We look forward to working with you.

Luce Choules. An expedition-based artist working primarily in the UK, France, and Spain, Luce uses fieldwork methods to pursue an in-depth geographic study of the landscape, communicating her discoveries through a variety of photographs, maps, books, and performance lectures. She is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society; founder of The Temporal School of Experimental Geography; has previously worked on mapping projects with Arts Catalyst, The Photographer’s Gallery and Turner Contemporary; and has been commissioned by several cultural organizations, including Burton Art Gallery, Ironbridge Gorge Museums and Centre Regional de la Photographie Nord–Pas-de-Calais, to develop projects affecting local communities and landscape.

An excerpt from Luce’s proposal:

The value of landscapes lies not in what we can take from them but what they have to give to us; in pristine and remote landscapes, we are our pristine and remote selves – we are not separate from nature, we are nature.

Rabbit Island, ‘itself an unsettled and undivided space’, provides an opportunity to investigate new geographic methodologies and artistic taxonomies. From the unique wilderness environment, I will consider how a remote landform could create meaning for a post-contemporary cultural imagination. Can an artist-led expedition discover new routes that establish the emotional significance of wilderness? What narratives can contemporary art practice add to a remapping of landscape?

[While in residence] a series of fieldwork surveys, written observations and photographic data gathered from the island will be used to compile an experimental guidebook. In using the format of a guidebook, I want to test how a poetic sensing of landscape can reimagine navigation, way finding and exploration. Can a book be a pathway? What are the emotional features of mapping? How can we move closer to landscape – can we be landscape?

Jack Forinash, Kelly Gregory, and Mary Rothlisberger. A collaborative team consisting of interdisciplinary artist Rothlisberger (Palouse, Washington), and architects Forinash (Green River, Utah) and Gregory (Oakland, California). Mary was a recent visiting artist at the IA MFA program at Sierra Nevada College and the Arts and Rural Environments Field School at the University of Colorado. Jack is a founding member and principal of the Epicenter: a housing, community development, and arts platform in rural Utah. Kelly works at David Baker Architects in San Francisco and has initiated several socially and ecologically-focused projects under her own Roving Studio. She currently lives on a sailboat.

Excerpts from the group’s artist statement and proposal:

Our background in community-engaged art and conscientious architecture merges thoughtful and deliberate research with radical creative action. The collaborative working process includes careful dialogue with the built, natural and social environments we are situated within. Each project connects with its surroundings and encourages social cohesion and considered action. Previously, our practices overlapped in rural Utah, where we have worked creating social systems and architectural interventions for a small town on the edge of the San Rafael Swell. We welcome the opportunity to shift perspective from the vast American West to Rabbit Island, a microcosm of our rapidly evolving world.

With existing technology, we’re training ourselves to see cities and islands from above, still and removed, abstractions in soft consistent colors. But when an island inhales, so does a shoreline exhale; these internal and sentient landscapes can be brought back to the life with the right set of tools. Re-contextualizing and sharing a story of place is ever-crucial because investment in landscape is the key to better stewardship of our living earth environment.

Buoys track weather, humidity, pressure, and wind, every 20 minutes. We can be human buoys. Our collaborative process of looking, listening, and translating will be represented so that someone else can root themselves into that ever-present moment of flux and feeling. From our research, we will produce a series of new living portraits of this place. Ideas include: bathymetric and topographic technical drawings through the island, stopping not at the water’s edge but continuing until a new extent is discovered; water depth measurements using rope segments; anti-data based in experience and feelings; drawings of the lakebed from exploratory diving; an island-sized drawing recording the minute changes in water level over a full day; circumambiations of the island from water; and maybe even a call-in hotline that dials a person-perspective (instead of a buoy). Like a landscape, our practice can shift, erode, accumulate and accommodate the shape of more mindful futures.

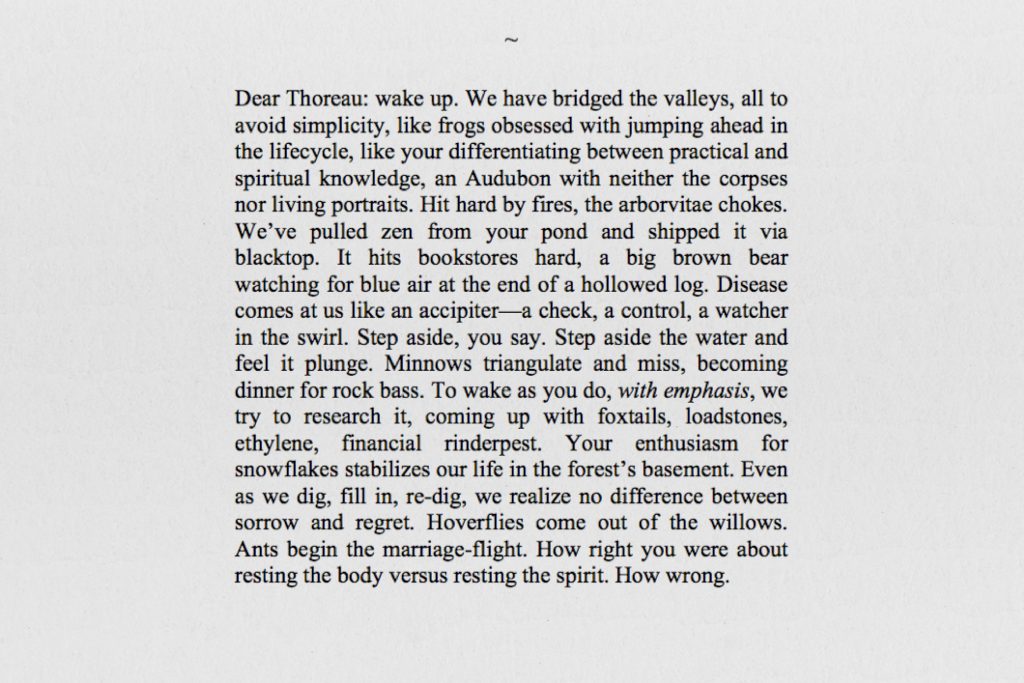

Frank Daniel Rzicznek. A poet based in Bowling Green, Ohio, is the author of two poetry collections and four chapbooks of poetry. Daniel’s work has appeared in The Kenyon Review, The New Republic, Boston Review, Orion, Gray’s Sporting Journal, and many other venues.

Excerpts from Daniel’s artist statement and proposal:

My work seeks to conflate and confuse natural, manmade, and mental environments to better delineate and challenge the divisions between each. Drawing from waking and dreaming observations, overheard speech, and textual material, my work hopes to speak/sing about humanity’s place in “nature” (my definition of which is ever-expanding) in the past, present and future, while synthesizing that nature with human history and consciousness. One belief my work frequently operates on is that a thought is just as real as an action. A fantasy and a memory can be on equal footing, and the chemical process behind imaginative thought is just as relevant as the physical atoms of the brain and the body. The result is a naturalist strain of surrealism that seeks to use image and metaphor to underline the minute-to-minute responsibilities of being human in a world at peril.

Seven years ago I began a long poem called “Leafmold.” Planned as a series of 365 interlocking pieces, one primary goal of the project is to conflate and confuse natural, manmade, and mental environments to better delineate and challenge the divisions between each. The poem draws from waking and dreaming observations, overheard speech, and textual material. (Some texts that have been reclaimed into pieces of “Leafmold” include the 1965 Audubon Nature Encyclopedia, a Cabela’s catalog, the complete lyrics of the Grateful Dead, and The Cantos of Ezra Pound to name just a few.) Using forms of narrative, epistle, and collage, I want “Leafmold” to speak/sing about humanity’s place in “nature” (my definition of which is ever-expanding) in the past, present and future, while synthesizing that nature with human history and consciousness. If offered a residency on Rabbit Island, my goal would be to compose pieces of “Leafmold” in as many microenvironments of the island as possible, including the waters of Lake Superior.

The work produced during my residency would function as a micro-manuscript within the larger 365 page work, one I would hope to complete and publish before the full project sees publication. The opportunity to work in the environs provided by the residency strikes me as completely unique. Not insignificant is the residency’s emphasis on the natural world and mankind’s dangerous, beautiful, tenuous place in it, an emphasis that I feel resonates deeply with the work I’m currently producing.

Walter van Broekhuizen. A multi-disciplinary artist from the Netherlands, working primarily in sculpture and installations. Walter attended the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. Since the mid-90′s his work has reflected the current human condition, often with regards to nature, using different mediums to remodel our perception of landscape.

Excerpts from Walter’s artist statement and proposal:

I address our abandonment of the wild, and how, despite it, we continue to listen to the vociferations of the wilderness we have abandoned. We find ourselves continually asking: what kind of a relationship do we have with nature? What is wilderness? Is there any wilderness left? It’s my belief that imagination, combined with a surrendering to and a fascination with nature, has the power to preserve our world.

“There are enough champions of civilization,” said Henry David Thoreau in his defense of the wild. The ‘civilized’ might argue that there are enough champions of wilderness. It’s a tug-of-war constantly in play as the world evolves into a place at once more civilized than ever, while abandoning the wild to become even wilder (though less understood). But despite our abandonment of the wild, an instinct remains within us; an undeniable call to raw, uninhabited landscapes, whether real or philosophical.

Rabbit Island is such a landscape. It’s there that I’d like to ask: what are we to do with that call that still exists within ourselves?

On Rabbit Island, I’d like to explore complete solitude and a landscape undisturbed by human accomplishment. I come from a country that nearly 1000 years ago was neatly divided into parcels, and now has no naturally wild places left. The Dutch relationship with nature is to tame it - until a few years ago, even deadfall in forests was cleared because it was considered ‘unnatural’. And nowhere in the entire country does the possibility exist to be somewhere and see no other human being.

I feel it’s our duty to listen to that instinctual call, to pay attention, and to ask how we are changing the world. I’d like to use Rabbit Island as a sketchbook - to create and photograph a series of ethereal sketches of the things that make up the island: rocks, pine needles, shadows, driftwood, whatever is naturally at hand - in a celebration of what exists, resisting the human tendency to tear down, build up, and conquer, by exploring the contours of the island’s natural patterns. I’d use the elements of nature and the play of light to proffer a new view of our relationship with it, ultimately asking: how much of nature do we take for granted, or even completely miss, by not paying attention, by choosing to create and live in less wild spaces?